Today, much of the Landes region in southwestern France is a forest, but over a century ago the scenery was different. Instead of an area densely covered with pine trees, there was a vast expanse of swampy terrain as far as the eye could see, without a road in sight. For centuries, the impoverished people who lived there came up with a way to negotiate the unforgiving landscape: walking on stilts.

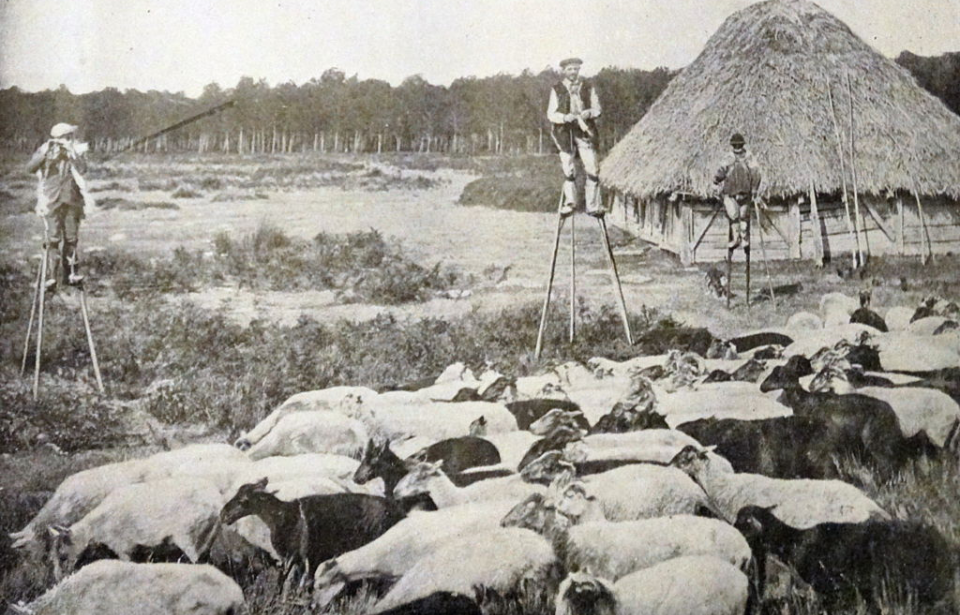

Stilt-walking shepherds

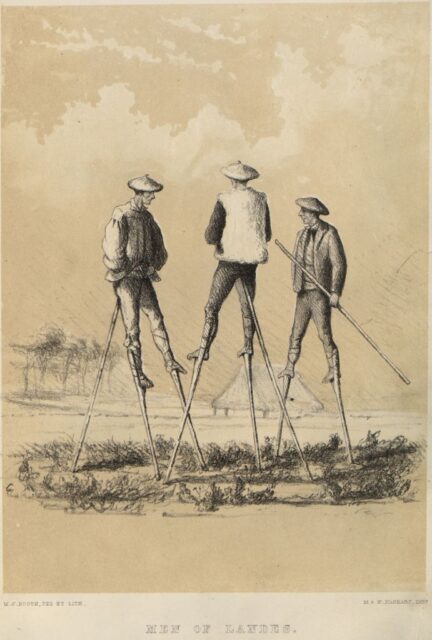

The stilts, called tchangues or “big legs,” were constructed of wood and stood approximately five feet high. They had wide straps to support the feet, and the part touching the ground was widened and made sturdy with sheep’s bone, not unlike small hooves. The stilts were so remarkably steady that the shepherds were able to live a large portion of their lives at a lofty height. Some were even dexterous enough to knit while watching their sheep.

A shepherd would carry a staff for extra support and to aid him in getting onto the wooden stilts. It was also employed as a crook to guide his flock.

Advantages of walking on stilts

This unique form of transportation enabled the shepherds to make their way through the countryside, which became particularly soggy after fierce rainfalls.

There were also other advantages to traveling several feet above solid ground. For one thing, perched up high, they could easily see and tend to their flocks of sheep, while keeping a lookout for ravenous packs of wolves. As well, the stilts helped them take longer strides, so they were able to cover longer distances in a shorter amount of time.

Who else walked on stilts to avoid the terrain?

Shepherds weren’t the only ones to possess this skill. Men, women and children were all talented stilt-walkers. They were trained at a young age, learning to perform some fairly amazing feats of balance and dexterity. Women, for example, could pluck flowers from the ground, while mail carriers delivered parcels on poles. Housewives shopped and gossiped at markets, and children did their chores and walked to school on stilts.

This delighted visitors to the region. It’s said that when Empress Joséphine visited Landes in 1808 to meet Napoleon, she and her court were greeted by a group of stilt walkers so adept that they were able to keep up with her carriage horses. Perhaps most impressive of all, Sylvain Dornon walked from Paris to Moscow, a distance of more than 1,740 miles, on stilts. The entire journey, occurring in 1891, took him just 58 days.

Why did the citizens of Landes stop using stilts?

Alas, stilt walking, along with sheep herding, came to an end in the Landes region at the close of the 19th century, as trees were planted and the marshland was drained.

More from us: Titanic II Ship – The Modern Rebirth of a Legendary Ocean Liner

That being said, they left a lasting mark on history, with an entry in the Scientific American Supplement in 1891 allowing future generations to learn about and become awe-struck by the stilt-walking shepherds. It reads:

“The shepherds of Landes … acquire an extraordinary freedom and skill … knows very well how to preserve his equilibrium; he walks with great strides, stands upright, runs with agility, or executes a few feats of true acrobatism, such as picking up a pebble from the ground, plucking a flower, simulating a fall and quickly rising, running on one foot, etc.”