In 1917, the tragic events of the Bolshevik Revolution brought the Russian Empire – and the rule of the Imperial Romanov family – to an end, thus beginning a whole new chapter in the history of the country.

Arresting the royal family

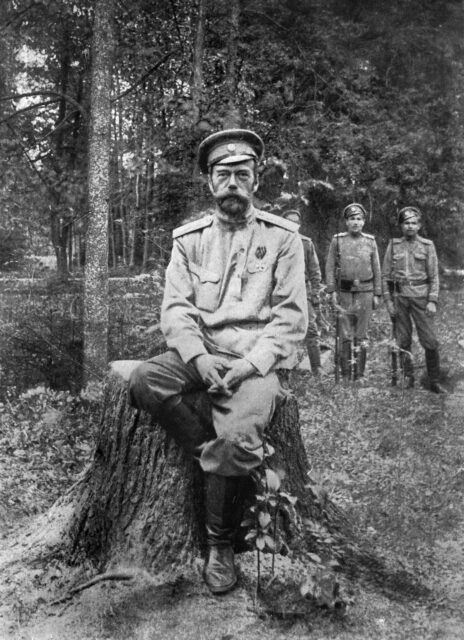

After the Bolsheviks seized power, forcing Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate, they arrested the Romanovs and sent the family into exile. They requested asylum from Nicholas’ cousin King George V of England but for internal political reasons were denied. The Romanovs were arrested at their palace in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) and then delivered to the city of Ekaterinburg 1,250 miles away where they were imprisoned in a two-story house under strict security.

According to historian and biographer Edward Radzinsky, Nicholas’ daughter, Grand Duchess Tatiana, described the new accommodation as “a small but cozy house with a tiny garden.” She wrote to her friend: “They separated a part of the street in front of the house for us to stroll i.e. walk back and forth 120 steps.” The Tsar also felt confined and wished to go out but most of the townsfolk, fresh from the horrors of WWI, hated the Romanovs.

Members of the family made regular entries in their journals that allow us to imagine their life in exile. They kept themselves busy with work and studies.

Teaching while in exile

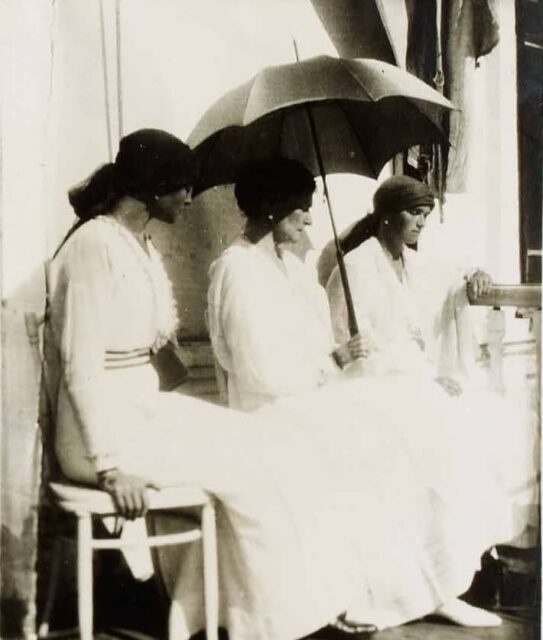

Nicholas II managed to persuade the supervising officer to provide tutors for his children – Grand Duchess Olga (22), Tatiana (21), Maria (19), Anastasia (17) and Tsarevich Alexei (13). They took daily classes and help the staff around the house. Anastasia wrote to her mother’s lady-in-waiting: “There are no changes here. It’s wet and dirty outside. There is a barn here where we all bring the wood. So much for fun. Nothing exciting, right? May Christ be with you, my darling.” In the evenings, the family gathered in one of the rooms to read and study the Bible. The Romanovs were devout Christians and when in despair, found solace in God.

The surviving correspondence between the family members is full of tenderness. They gave each other nicknames, shared funny stories about their pets, some of which accompanied them in exile. Young Alexei especially loved his dog Joy and by a remarkable twist of fate, the spaniel was the only member of the family to survive the Revolution, make it to England and be buried at the Windsor Castle cemetery.

The Romanovs remained social while in exile

The Romanovs were followed everywhere by the watchful eyes of armed soldiers. Their correspondence was censored and strictly limited. In spite of this, they never treated their captors as enemies, which is confirmed by numerous memoirs and letters.

On December 12th, the Imperial children’s tutor, Pierre Gillard, made an entry in his journal saying, “The Grand Duchesses, in their charming simplicity, loved talking to these people. They would ask the soldiers about their families or battles they were in during the war. Alexei also won their hearts, and they tried their best to make him happy.”

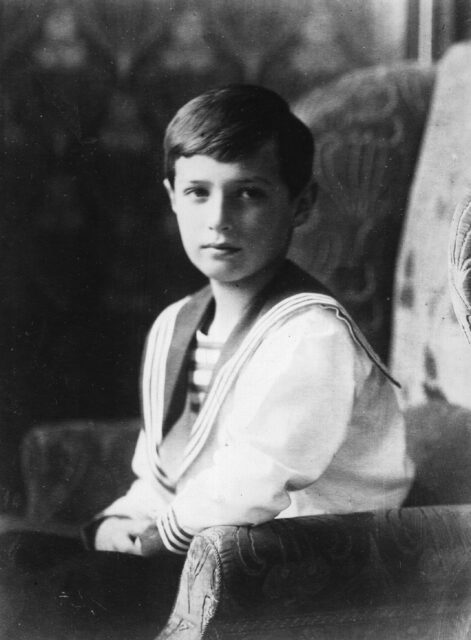

Alexei’s condition

Apart from lack of fun, there was a much more significant factor that made imprisoned life unbearable. Alexei, the heir to Nicholas II, suffered from haemophilia, a rare genetic disorder in which blood doesn’t clot normally. This ailment could make any injury deadly, and a minor bruise could sometimes be followed by days of painful recovery. His condition was a constant concern for his parents. It was one of the main reasons why Alexandra requested the help and guidance of Rasputin, who possessed an unexplainable power to relieve Alexei’s pain.

New supervision

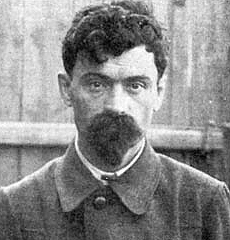

Life in exile toughened when the Provisional Government commissioned a new group of shooters to replace the old guards of the imprisoned family. The group consisted of recent political prisoners and members of anarchist gangs that formed the new power structure. They forced the former Tsar to take off all military insignia and issued numbered ID papers for every family member. It was not allowed for the children to play on their ice-slide or use their camera anymore.

Soon after, the Romanovs met the new house commandant named Yakov Yurovsky. In Radzinsky’s biography of Nicholas II we find his first impression: “If this hadn’t been the detested imperial family, one could have considered them as simple people of no arrogance.” He sent away the royal entourage including the tutor Gillard, which is when the Empress began to suspect that something terrible was about to happen.

On the dreadful day of July 16th, Yurovsky took the cook boy from the kitchen and Alexandra wrote in her journal: “Completely out of the blue Lika Sednev was sent away to meet his uncle. I wonder if it is true and if we will ever get to see the boy again.” The events of the following night have been described in numerous memoirs of eyewitnesses. From Yurovsky’s notes: “Having called the shooters who were chosen for the execution, I assigned the roles and directed who will shoot whom.”

The beginning of the execution of the Romanov family

At midnight, Yurovsky told Dr. Botkin to wake the family up and, having explained that there were disturbances in the city, told them to follow him down to the “safe place” in the basement. Nicholas II was carrying Alexei who had previously hurt himself and wasn’t able to walk. The girls brought some pillows, along with their little dog.

The basement was a small room lit up by a single lightbulb. The Empress asked for some chairs as it was painful for her to stand. Yurovsky’s assistant rushed out and remarked to his comrade with a smirk: “They want to die in chairs… Very well, we shall bring them the chairs.”

Empress Alexandra and Alexei sat down. Yurovsky started explaining that he wanted to take a photograph of the family to put an end to the rumors about their escape and began to position them in a specific order.

Announcing their fate

The Empress and Alexei sat in front with Nicholas standing beside them, the Duchesses stood behind and the servants, including the faithful Dr. Botkin, were at the very back. These actions didn’t cause any suspicion as everyone knew that the commandant was a keen photographer and there was a camera in the house. Yurovsky then gave a sign for the execution squad to come in.

The Tsar stepped forward, protecting his family while Yurovsky read out the sentence: “Nikolai Alexandrovich, in view of the fact that your relatives are continuing their attack on Soviet Russia, the Ural Executive Committee has decided to execute you.” The Tsar looked at him in astonishment and asked: “What? What?” According to one of the shooters who was standing close by, Nicholas turned to his family and said: “forgive them for they do not know what they do!”

In a split second, the shooting began. The Tsar fell to the floor immediately as most of the shooters aimed at him. The Empress, the doctor and the servants were killed as the rest of the squad started firing their guns chaotically from the doorway over each other’s shoulders.

It was not a clean execution

The daughters were thrashing about the room, crying for help in the thick smoke, with bullets ricocheting from their bodies. Yurovsky wrote: “I couldn’t stop shooting for a long time and it acquired a disorderly character. I realized that many were still alive.” The squad had to wait for the smoke to die down while crying and moaning could be heard coming from the room. One of the shooters recalled: “two of the younger girls were sitting on the floor by the wall, covering their heads with their arms, with two shooters firing directly at them.”

Another executioner reported: “Blood was dripping in streams. When I returned I saw the heir still alive, he was moaning when Yurovsky came up close and shot him three times. The scene made me sick.” The shooters brought bedsheets and began to carry the bodies to the truck that had been previously prepared.

Finishing what they started

The squad was carrying the bodies outside when all of a sudden one of the Duchesses rose up from her stretcher, looked around, gave a shrill cry and covered her face with her hands. At the same time, her three sisters started moving around on the floor, covered in blood. The shooters were horrified by this mysterious survival. As the doors to the house were open, it was decided to bayonet the daughters instead of firing the guns again.

However, the dull blades couldn’t penetrate their garments and it was discovered that the Duchesses and Alexei had a large amount of diamonds and jewelry sewn into their clothes, protecting them from the bullets and bayonets. Ultimately, their suffering was put to an end when one of the men grabbed his revolver and shot each of them in the head.

Burying the family

Finally, all the mutilated bodies, which had also been doused with sulphuric acid, were unceremoniously thrown into an unmarked pit. The commandant noted that when all the children were stripped, they had handmade sacks containing bits of Rasputin’s teachings along with his portrait around their necks.

For a while afterward, a rumor was spread around the country and abroad that only Nicholas II had been executed whilst the family had been evacuated to a safe place. It was only in 1926 that the extent of the executions became known to the public.

The burial site remained hidden until 1979 and little by little the remains of the Romanovs were unearthed, with the final discovery happening only in 2007.

Read another story from us: The Violent End of Rasputin – Details of his Fateful Last Night

In 2000, Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra, and their five children were recognized by the Russian Orthodox Church as saints. As Empress Alexandra had once written to her friend: “All of us share the simple desire to live in peace, like an ordinary family, away from politics, conflict, and intrigue.”