When one thinks of Nazi concentration camps like Auschwitz, music is certainly not the first thing that comes to mind.

However, a music theory professor from the University of Michigan has recently unearthed what is believed to be one of several popular pieces of music played at Auschwitz.

Auschwitz, in Poland, was one of a network of concentration camps set up by the Nazis during the Second World War. It was first built to house Polish political prisoners, the first of whom arrived at the camp in 1940.

It consisted primarily of three parts: Auschwitz I, the original section; Auschwitz II-Birkenau, which was both a concentration and extermination camp; and Auschwitz III-Monowitz, which was a labor camp. Auschwitz II-Birkenau was one of the largest sites of Jewish extermination: around 1.1 million people are believed to have died at the camp, 90 percent of whom were Jews.

Life in the camps was extremely hard to say the least. Prisoners’ days lasted from between 3:00 and 4:30 in the morning (depending on the season) until the evening. They had little food, no rest during their 12-hour workday, and accommodations were beyond deplorable. Sanitary conditions were miserable, with inadequate latrines until some were installed in 1943, and little fresh water.

Vermin like rats and lice were rampant, and many prisoners died of typhus and other bacterial infections, not to mention starvation and malnourishment. In short, it was a brutal, horrifying existence for all who were imprisoned.

So it is surprising, perhaps, to discover that the music played at Auschwitz was particularly upbeat. According to Professor Patricia Hall, who examined the manuscripts of music from the camp, she was “completely thrown” by the song titles, let alone the actual music.

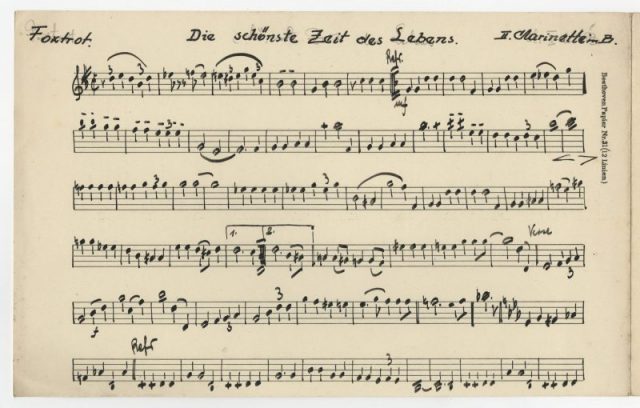

Hall had traveled to Auschwitz in 2016 with the hope that she could learn more about the music that had been played at the camps during the Second World War. Two of the more popular song titles translated as “The Most Beautiful Time of Life” and “Sing a Song When You’re Sad.”

Over the next two years, she examined several other hand-written music manuscripts that had been arranged and performed by prisoners. Eventually, this led to the performance of one of these pieces for the first time since 1945.

In essence, Hall wanted to resurrect the music that had been lost to time after the liberation of the camps. “I’ve used the expression, ‘giving life,’ to this manuscript that’s been sitting somewhere for 75 years. … Researching one of these manuscripts is just the beginning — you want people to be able to hear what these pieces sound like. … I think one of the messages I’ve taken from this is the fact that even in a horrendous situation like a concentration camp, that these men were able to produce this beautiful music.”

In order to make this happen, she asked for help from another university professor, Oriol Sans, who is director of the Contemporary Directions Ensemble, as well as Josh Devries, a graduate student who was able to transcribe the manuscripts into music notation software in order to make them easier to read and play.

In October 2018, the ensemble gathered to record “The Most Beautiful Time of Life.” In its first public presentation since the Second World War, the piece was performed at a concert in November 2018 at the University of Michigan.

When Professor Patricia Hall played the recording at one of her university lectures, the audience was visibly uncomfortable. The piece is upbeat, a foxtrot, and featured “euphoric lyrics” about falling in love in the spring and cherishing one’s precious time. It was not at all what her audience was expecting: “I’ve heard various adjectives used to describe this foxtrot, even like ‘twisted,’ given the situation that it was performed in and created in.”

Using data from the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, Hall was able to identify the three musicians who had originally arranged the music, as two of them had signed it with their prisoner identification numbers.

They were Antoni Gargul (number 5665) and Maksymilian Pilat (number 5131). And because the museum’s archives also had photographs of the two men, Hall was able to put faces to the names associated with the manuscript. As she stated, “The transformation of going from a number to the face of this person was a very dramatic experience for me.”

Both museum officials and survivors of the concentration camps have stated that musicians received more food, clean clothes and were spared from the hardest labor. They would be stationed at the gates of the camp to play cheerful marching music for the prisoners as they left for work.

However, they were not entirely immune to the camp and all of its horrors. According to Hall, “We like to think of a narrative in which the musicians were saved because they had that ability to play instruments. However, it’s been documented by another prisoner (in an orchestra) that around 50 of them … were taken out and shot.”

Something unusual struck Hall about the “Most Beautiful Time of Life,” however. It was arranged only for a tuba, trombone and violins, which were not likely to have been used in a work orchestra. She deduced that there had actually been a dancehall at Auschwitz: “They would play Sunday concerts in front of Commandant [Rudolf] Höss’ villa … playing for at least one hour these dance arrangements, so that soldiers, SS, could dance.” This would explain its foxtrot tempo.

While, understandably, many people still had strong adverse reactions to the music, Hall has come to her own conclusion: “What’s finally resolved it to some degree for me … is the fact that given the worst conditions possible — many of which we can’t even appreciate — these men still managed to create this joyful, beautiful music.”

Music therapy has been used for years in professional contexts with amazing results. So it is not hard to understand why, while living in somewhere as horrifying as Auschwitz, the human spirit would rise to make music in order to combat reality. That this music has survived and been resurrected, makes it all the better.