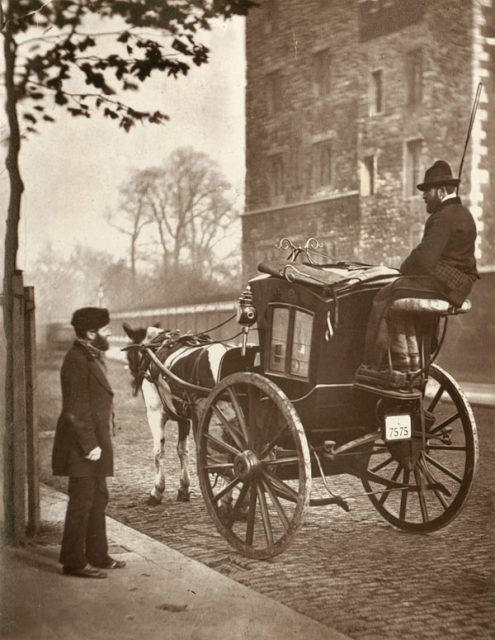

In England during the Victorian Era, hailing a taxi meant flagging down a hansom cab. Hansom cabs were designed by Joseph Hansom, in 1834, and patented by John Chapman two years later.

The cabs were two-wheeled affairs, low to the ground, and the cab’s driver would perch on an elevated seat at the carriage’s rear. A hansom cab could seat two passengers who entered the closed passenger box through a folding door at the front.

The design made the vehicle both swift and less prone to upset when going around sharp corners, making it the most popular and common type of hired cab during the Victorian era.

It wasn’t a bad way to travel if you were the paying fare, but it could be much less pleasant if you were the one doing the driving. The driver’s box was exposed to the elements, which made driving a cab pretty miserable work when the weather was cold, wet, or windy, and all of those were conditions that were pretty common.

As a result, London’s cabbies had frequent need of warm drinks or food. It’s no surprise, then, that cabbies who were cold and miserable would go, according to CabbyBlog, to the one place that could offer them warmth or sustenance – public houses, or pubs.

There were several drawbacks to hanging out in pubs, though. One was that it was illegal to leave the horses unattended, so a cabby had to pay someone to hang out and watch his horses. Another drawback was that the pubs were full of opportunities to gamble or drink, neither of which were desirable activities for someone who was on the clock.

According to the BBC, it was a man named George Armstrong who first came up with a solution to the problem after he was unable to find a cab during a blizzard when all the cabbies were huddled in the local pubs, trying not to freeze.

He met with a group of philanthropists, including the Earl of Shaftesbury, to brainstorm a solution to their problem, and, in 1875, the Cabmen’s Shelter Fund came into being.

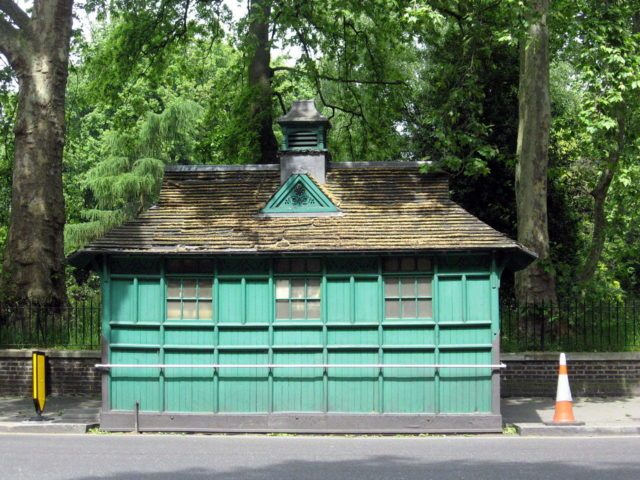

The Fund was responsible for building a series of small, green shelters around London. There were originally more than 60, scattered along public byways, and none of them were larger than a horse and cart to stay in compliance with Metropolitan Police rules.

Related Video:

https://youtu.be/MssjjdVAj6k

Each of the tiny shelters offered food, hot drinks, and a place for cabbies to get out of the weather that was independent of the pubs. Furthermore, there was the added advantage that the shelters had rules prohibiting gambling, swearing, political discussions, and most of all, drinking.

Hidden London notes that the amenities varied from shelter to shelter, depending on its location, with some being extremely basic and others nearly being luxurious. Many of the shelters ended up with their own nicknames, such as the Bell and Horns, or the Junior Turf Club.

The latter earned its name due to its proximity to the aristocratic club of the same name that was located nearby. In the 1920s, champagne-toting members of the club would periodically invade the nearby shelter. All of the shelters were built with places to tether one’s horses around the outside and troughs to water them.

Various small bits of history have passed through the tiny shelters over the years. In September 1888, a man identifying himself as “Dr. J. Duncan” confessed to the Jack the Ripper murders while he was at the Westbourne Grove shelter.

Sir Ernest Shackleton, the noted Antarctic explorer, was a frequent visitor to the Hyde Park Corner shelter. Painter John Singer Sargent was a regular at yet another of the small shelters.

Unfortunately, many of the shelters were destroyed during the Blitz in World War II. Still others met their demise during redevelopment ventures or road-widening projects. Today, only 13 of the huts remain, and 10 of them are still in operation.

Even though the days of Hansom cabs are long gone, the shelters that remain in operation still serve London’s cabbies. Only licensed black-cab drivers, those who have passed the Knowledge Test – to have memorized all the streets and routes in the city – are allowed to sit inside the shelters.

Most of the shelters now only operate from around seven in the morning until one in the afternoon. The cabbies can sit at one of the long, thin tables and get a hot drink. The shelters also generally serve eggs, bacon, sausage, and some sandwiches.

The cabbies who use them come in for the company of their peers as much as the food. Although only cabbies are welcome to come inside the tiny huts, several of them also have windows where the public can order food to take away, which helps bring in more money.

Today, the shelters have Grade II status as buildings of historical interest, which means that not only should efforts be taken to preserve them, but also that any refurbishment has to be consistent with their original style, right down to the shade of green they can be painted.

As a result, fully redoing one could cost as much as £30,000. The cost of repairs and maintenance is still absorbed by the Cabmen’s Shelter Fund, but modern cabbies and shelter-tenders alike know that things are changing.

With the rise of ride-sharing services like Uber, the trade is slowly dying out. Even so, all of the people who are connected to these small shelters are adamant about wanting their history and legacy preserved.

Read another story from us: People are Starting to Sleep in Medieval “Box Beds” Again

Colin Evans, a long-time London cabby, phrased it well, “It’s not just the buildings. It’s the characters, too. If we lose this, we lose part of the cab trade’s history and a part of London history. That would be a real shame.”