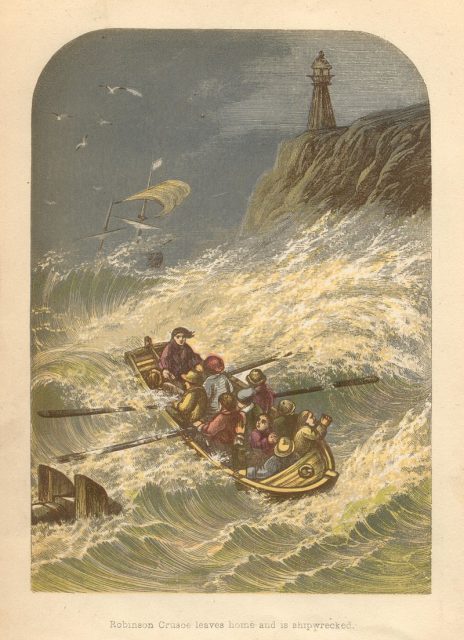

It was three centuries ago, on April 25, 1719, that Daniel Defoe’s defining work of fiction, Robinson Crusoe, saw the light of day in its first printed version. The book, an early example of novel writing in Britain, recounts how Crusoe, who is born in England, survives a shipwreck only to end up stranded on a lonely Caribbean island for the next 28 years of his life.

Robinson Crusoe occupies an important place in the history of literature and has helped describe the novel as a genre. More than that, the book relates to the British Empire during a particularly prolific era when much of the world was administered from London.

On the anniversary of Robinson Crusoe’s original publication — a list of things related to the book perhaps you knew little of.

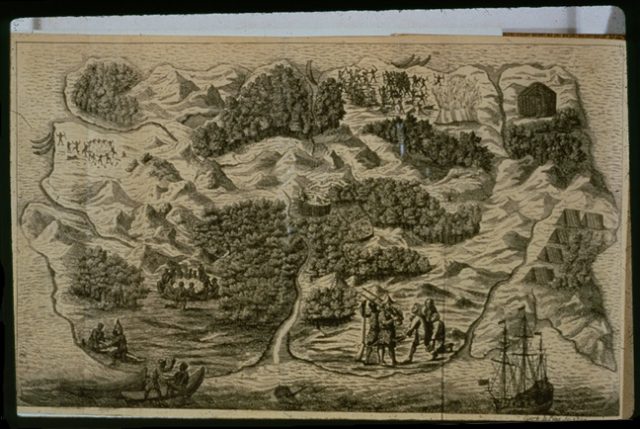

The location of the island

According to the Guardian, just a few months before Robinson Crusoe was published in the spring of 1719, its author Daniel Defoe wrote in one magazine that the British joint-stock South Sea Company should supervise the initiation of a new colony of Britain on the coastline of what is now Venezuela, at the mouth of river Orinoco. The company he mentioned was relatively new at the time and was already managing a contract with Spanish colonies across Latin America where slavery was ongoing.

This is an example of how various elements of Defoe’s book are relatable with the era of colonialism. Defoe located the fictitious island where his main character is wrecked roughly 40 miles away from the designated location of the new colony. The desolate island is also close to Trinidad, the bigger of the two main islands comprising the island nation of Trinidad and Tobago today.

Defoe presented a more benevolent island environment compared with the real island where the castaway who was the inspiration for the character of Robinson Crusoe was stranded a few years earlier.

Related Video:

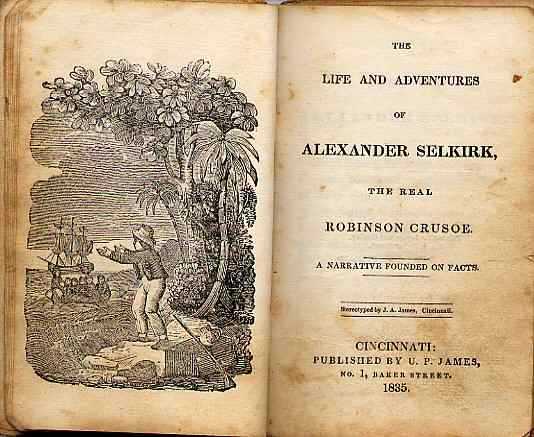

Crusoe was modeled on real castaway Alexander Selkirk

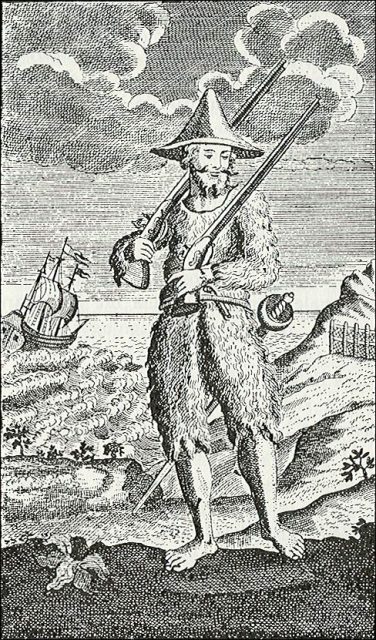

Many believe that Defoe based the fictional character of Robinson Crusoe on Scottish-born sailor and Royal Navy officer Alexander Selkirk. Born in 1676, Selkirk was a man of a restless spirit. In 1703, after he a huge quarrel with his family, he left Scotland, sailing on a privateer vessel. The living conditions aboard that ship were poor. Nasty conditions such as dysentery were always threatening someone’s health.

As the story goes, the ship lost its captain one day and control was taken over by one Lt. Thomas Stradling, with whom Selkirk did not get along so well. Tensions between the two reached a head while the ship was anchored in the shelter of a deserted island in the South Pacific, in 1704.

When Stradling insisted the crew continue the journey, Selkirk objected. He took a gamble, hoping that other members of the crew would join his “rebellion,” and declared that he was staying on the island until repairs were conducted to their vessel. His main argument was that the ship was too weak and would not endure the dangers the ocean might expose them to. Ironically, he turned out to be right at the end.

Stradling did not listen to Selkirk’s argument; even worse, nobody else dared step ashore to support Selkirk. In the end, Selkirk was refused permission to return aboard the ship — the captain set sail, leaving the man behind with few resources to survive.

Selkirk had to cope with the conditions of the island in a similar fashion that Robinson Crusoe did in the novel, before he was saved…four years later. At least he didn’t lose his life. The ship which abandoned him indeed sank, killing almost the entire crew.

It’s an urban myth that Daniel Defoe met Alexander Selkirk at the Llandoger Trow public house in Bristol, England which sadly, after 350 years of operation, called last orders on April 20th.

The religious notion to Robinson Crusoe’s character

After Robinson Crusoe became a castaway on a wild island, he attempted to recreate at least some bits of the world which he once knew. The island became the home of his deepest fears and loneliness, but also creation and resilience.

Crusoe was fortunate enough that the shipwreck still contained some necessary tools for work and building, as well as grain and gunpowder. Also, he was not superior in his knowledge. It took some time until he managed to hone some of his skills, such as properly growing crops and producing bread.

In a reflection to the island experience, Crusoe considered that ending up as a castaway was God’s punishment for he had not listened to his parents and ignored their words as he set out on the arduous journey. As the reparation for his wrongdoing comes to an end, he goes back to Britain, only to find his life there was no longer his life. In his decades-long absence, almost everything had crumbled into obscurity.

Friday was a pioneering character for fiction

On the island, Crusoe meets Friday and the two characters function as a binary opposition. While Crusoe can be interpreted as an early embodiment of colonialism into fiction, Friday is the symbolic embodiment of the oppressed. More than that, Friday is also the first non-white character in fiction to be provided a voice and individualism.

In the novel, Friday is not Crusoe’s slave, although since his life is saved from the ferocious cannibals, he is sort of indebted to Robinson as a gesture of appreciation. Crusoe feels naturally superior in this relationship, but comes to display a greater appreciation for Friday. In one instance Crusoe even says he loves Friday — an extraordinary acknowledgement in itself.

The importance the book had to literature

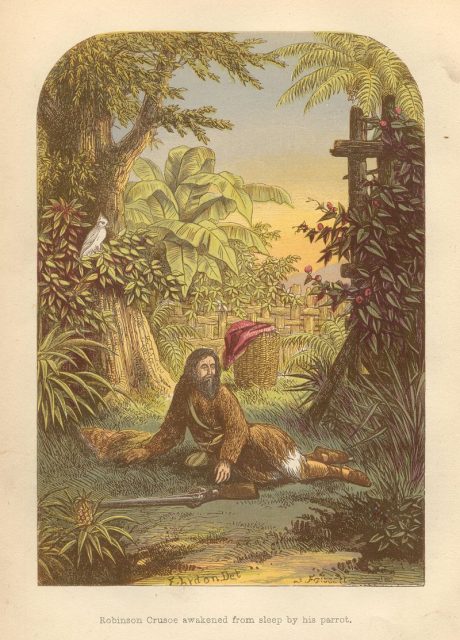

‘Robinson Crusoe is awakened by his parrot’ – illustration by Alexander Frank Lydon

Defoe wrote Robinson Crusoe as a confessional, autobiographical novel, deeply developing the inner world of its main character. This new approach to writing fiction proved incredibly popular, especially among middle-class readers.

The book appeared in the 18th century when the term “novel” was virtually non-existent. It even led to the formation of a new literary genre — the Robinsonade — where characters are in a similar manner left as castaways to survive on remote, isolated islands.

Read another story from us: Robinson Crusoe was Based on a Real-Life Castaway

There is an array of other works of fiction which revolve around similar topics as treated in Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, including William Golding’s Lord of the Flies from 1954 and Umberto Eco’s The Island of the Day Before from 1994.