For those who can’t go on actual archaeological digs you can now digitally excavate artifacts. When cities dig into the bowels of the Earth to lay new subway tracks, it’s impossible to predict what kind of ephemera will surface in the bulldozers’ wake.

The new Metro line in Amsterdam, Holland, begun in the early 2000s, runs along the Amstel River, and endless gallons of water had to be drained and diverted to make room for the new tracks. A trove of items, everything from pottery to books to stamps, retrieved from the site now form a collection known as “Below The Surface”.

A brief documentary about the process of digging up the objects, and the collection itself, is presented on the Below the Surface website.

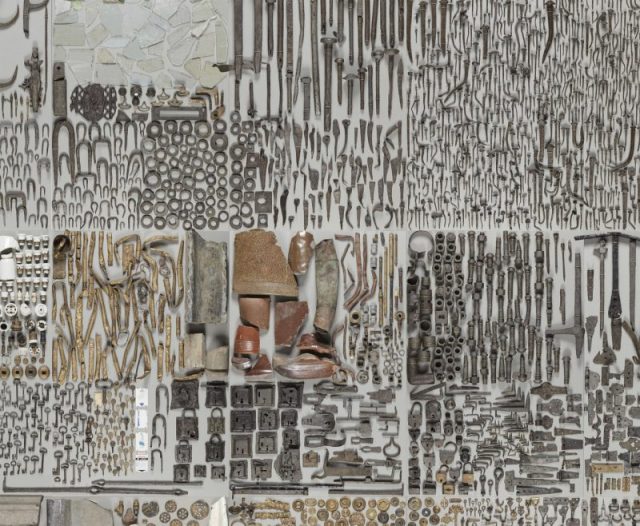

Some of the objects are ordinary and not relics of a bygone age: a broken plate, for example; a car’s license plate; a miniature statue of the Eiffel Tower in Paris. But other items are extraordinary, such as a pipe cover that has a portrait of Dutch Naval Lieutenant Jan Carel Josephus van Speijk.

A 16th century hunter’s belt found by the archaeologists bears the inscription, “I am a hunter and now have what delights me.”

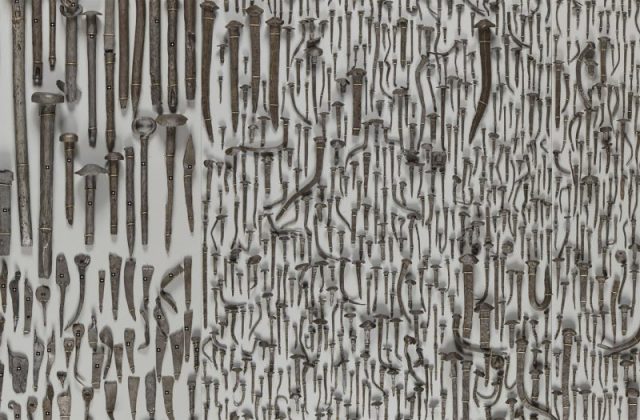

There are hair combs, pots of paints, inkwells, buttons, anchors, and pieces of pottery that have been carefully glued back together. In total, the collection has more than 700,000 items. It took nine years, beginning in 2003, for the metro line to be excavated. Rather than take the items found to landfill, government officials made the wise decision to turn the everyday objects into art.

Related Video:

This is Colossal explains that it was a joint project between the Department of Archaeology; Monuments & Archaeology, and the City of Amsterdam. The interactive website, Below the Surface, offers detailed insights into how the project began and then unfolded and why archaeologists felt it was a powerful opportunity to explore the city’s history.

The goal was to provide the public with context of how the Amstel River fit into the city’s past and to show those interested how to digitally excavate artifacts. It was once a key artery into Amsterdam’s center that accessed a trading port about 800 years ago.

It was a rare chance for scientists and researchers to find physical evidence – and preserve it – that revealed clues about the people who lived in the city over the years and, specifically, those who made their living along the Amstel.

On the website’s introductory page, it is noted that the project along the Amstel was unique in several ways. “Rivers in cities are unlikely archaeological sites,” it begins.

“It is not often that a riverbed let alone one in a major city, is pumped dry and can be systematically examined…Damrak and Rokin (the spots of excavation) proved to be extraordinarily rich on account of the waste that had been dumped in the river for centuries and the objects accidentally lost in the water.”

“The enormous quantity, great variety and everyday nature of these material remains make them sources of urban history.” It continues, “every find is a frozen moment in time.”

The building of the Metro line was first considered by the government in the 1960s, but another route was prioritized instead. Furthermore, excavation techniques needed to cope with the soft clay and sand that comprise the soil along the route made the engineering challenge extraordinarily difficult. It took years for those techniques to be developed to the point at which they could be used safely to bore through the materials along the riverbed.

Now, the Amstel line and the unique, tremendously varied artifacts the collection offers the public, means it isn’t just moving Dutch folk to and from a destination. Along the way, it teaches them about their history – as a city, a people, and a nation and it teaches people how to digitally excavate artifacts. Fittingly, many of the objects are mounted and on display at the new Rokin line, which opened in July, 2018.

Read another story from us: Mudlark Discovers Giant Mammoth Tooth on the Banks of River Thames

The collection is the best possible outcome, and it is evidence of what can be achieved when commerce, transportation, art, and culture work together toward a common goal.