A prehistoric fossilized brain is baffling and exciting scientists. Ever since archaeology became a respected scientific discipline, teams have uncovered everything from tools to tombs, skeletons of man, and bones belonging to dinosaurs, animals, and long-extinct species like woolly mammoths.

But actual organs have been elusive, largely because organic matter simply can’t be preserved so it will last for any length of time. Whether they belong to human, animal or marine life — organs are made of organic material and simply break down eventually.

Brain matter, specifically, has been so susceptible to decay that even the ancient Egyptians, masters of mummification and body preservation, usually removed the brain before beginning the procedure, except the heart. Often, the heart has been found in Egyptian mummies, but only rarely has a brain been found.

New evidence, however, is giving researchers, archaeologists and other experts a glimmer of hope that perhaps brains don’t always decay, that perhaps some fossilized brains exist elsewhere, in rock formations or burial sites not yet discovered. The reason for this new optimism is a study done by three scientists at Harvard University, who have been examining brain and central nervous system (CNS) matter in a Cambrian fossil. Findings from their study were recently published by the Royal Society of B, a scholarly journal.

Check our study @RSocPublishing on fossil nervous tissues🥳 w/@PlLife2 @StephenPates we show that 3 Cambrian BST sites replicate congruent neuroanatomical data on Alalcomenaeus, supporting a true biological signal 🤓 no🦠🎞️here! @HarvardOEB @MCZHarvard #OAhttps://t.co/KykuqeyxzG pic.twitter.com/M6lj19Sz6Q

— Javier Ortega Hernández (@InvertebratePal) December 11, 2019

The team studied a small Cambrian creature whose formal, scientific name is “Alalcomenaeus,” a type of 500 million year old arthropod, or insect. Experts say that, while this little being may have been tiny, its exoskeleton was strong enough to shield it from deterioration.

The team said, there was an “unusual abundance of exceptionally preserved (animal and plant life) in Cambrian deposits, which capture details of the non-mineralized anatomy that would normally be lost to decay…” In other words, the material that surrounded this little entity in death kept its brain matter from wholly disintegrating, as normally happens with man, animal or insect.

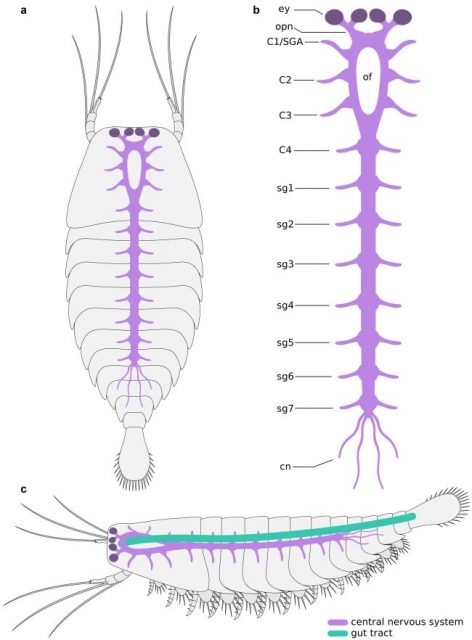

This creature’s brain was not remotely like a human’s of course, but the fact that it endured at all is startling. The “brain” of the prehistoric creature was more of a central nervous system, with elongated brain structures that ran from its head to its upper back. Neural tissue connected to the creature’s four eyes and four pairs of segmented nerves. More nerves from the brain extended all the way down its backside.

This system of nerves appeared as a dark stain on the specimen, but because neural tissue is rich in carbon, the traces of carbon in that stain gave it away as a brain fossilized for an estimated, and absolutely amazing, 500 milion years. The findings have dazzled archaeologists, palaeontologists and other researchers who have historically assumed that all brain matter of all beings decays after death. No matter how sophisticated the burial, fossilization or mummification, brains have commonly been thought to wither and sink back into the earth from whence they came.

In fact, experts believed that the process of decay began long before any preservation process could have been started, which may explain why the Egyptians tossed them away. But the findings at Harvard have shown that, depending on the environment in which the brain is kept, that decay might just be stopped.

The Harvard experts are hopeful that their findings will lead other scientists to stop drawing conclusions about what may — or may not — happen to the brain when its host dies.

“Our study represents,” their report begins, “to our knowledge, the first case of consistent anatomical organization of the exceptionally preserved CNS,” and continues on to note that experts should “gravitate away from the preconception that nervous tissue is too labile (easily altered) to become fossilized, as evidence keeps accumulating that neurological preservation is possible (under certain conditions).”

Related Article: Fossil Reveals that Snakes used to Walk on Hind Limbs

Getting other scientists and experts to reconsider their long-held point of view may be difficult. But the team hopes that, in light of their new evidence, open minds will prevail.