What was the purpose of this wall of bones? Centuries ago, just like today, people often asked to be buried at, or near, their church, and many cathedrals and churches have cemeteries close by or beside them, to accommodate the wishes of their congregations. As Europe became more heavily populated and the need for larger cemeteries arose, churches would sometimes begin building them but never, ever, forget those who had passed away already and lay nearby.

Remains could not merely be bulldozed or moved, and that may be why a “wall of bones” has been discovered near a cathedral in Belgium; officials used the skeletons of the already dead to build a structure that kept them near their church.

That, at least, is the rationale being proffered by experts and archaeologists in the city of Ghent, Belgium, where a wall constructed entirely of human bones has been discovered. It is made solely of thigh and shin bones, and fragments of skulls, and while it is a grisly site to most people, experts say it is nothing of the sort, and can be easily explained.

The wall at St. Bavo’s Cathedral is currently being examined and tested, but archaeologists told the media recently that the bones date back to the 15th century, while the wall itself dates to the 17th or 28th century. In all likelihood, the team said, the old cemetery was being moved or expanded, and something had to happen to the bones that already lay there. Hence, grave diggers simply used them to fashion part of the new cemetery.

But experts admit the sight is unsettling, to be sure. Janiek De Gryse, lead archaeologist studying the find, told Fox News and other media outlets, “This is a phenomenon we’ve not yet come across here,” he acknowledged. “For the moment, we would place the actual construction in the 17th or 18th century, although there’s a great deal of research still to be done.” Similar structures have been found in Paris, used to construct parts of the famous catacombs that lay beneath the city.

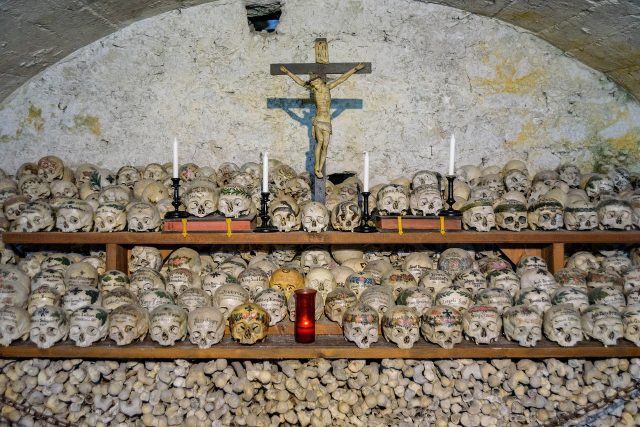

De Gryse continued, “When clearing a churchyard, the skeletons cannot just be thrown away. Given that the faithful believed in the resurrection of the body, the bones were considered the most important part. That is why stone houses were sometimes built against the walls of city graveyards: to house skulls and the long bones in what is called an ossuary.”

Finding human remains while starting construction on something new is surprisingly common in Europe and the U.K. Earlier this month, 40 skeletons were found, with their hands bound behind them, when a new project got underway in Buckingham, in the south of England. Experts studying the find suggested that they may date back to Anglo-Saxon Britain, between the 5th and 11th centuries, or they are victims of the English Civil Wars, which were fought between 1642 and 1651.

Another theory is that they were merely criminals who were executed for whatever transgressions they had committed. Other areas in Europe are proving to be just as rich in archaeological finds as Belgium and the U.K. In January, experts at the Archaeological Museum in Gdansk told Fox News that four Scandinavian warriors were found buried in northern Poland. The bodes are undergoing tests now.

“Men, probably warriors, were buried in them,” explained lead archaeologist Dr. Slawomir Wadyl, of the museum, when describing the graves. He added that this became clear “as evidenced by the weapons and equestrian equipment deposited with the bodies.”

Related Article: Renovations at Lincoln Cathedral Unearth 50 Mysterious Medieval Burials

And so, when discoveries like the one recently made in Belgium are reported, it is easy to grimace and find the whole thing rather macabre. But for scientists, archaeologists in particular, these finds offer rich opportunities to delve into the cultures, people and rites that existed so many centuries ago. And what they learn, and what they teach us about our past, makes us aware that our ancestors were not all that different from many folks today; they exercised their faith by going to church, and asked to be buried near the institution that, in life, gave some so much comfort.