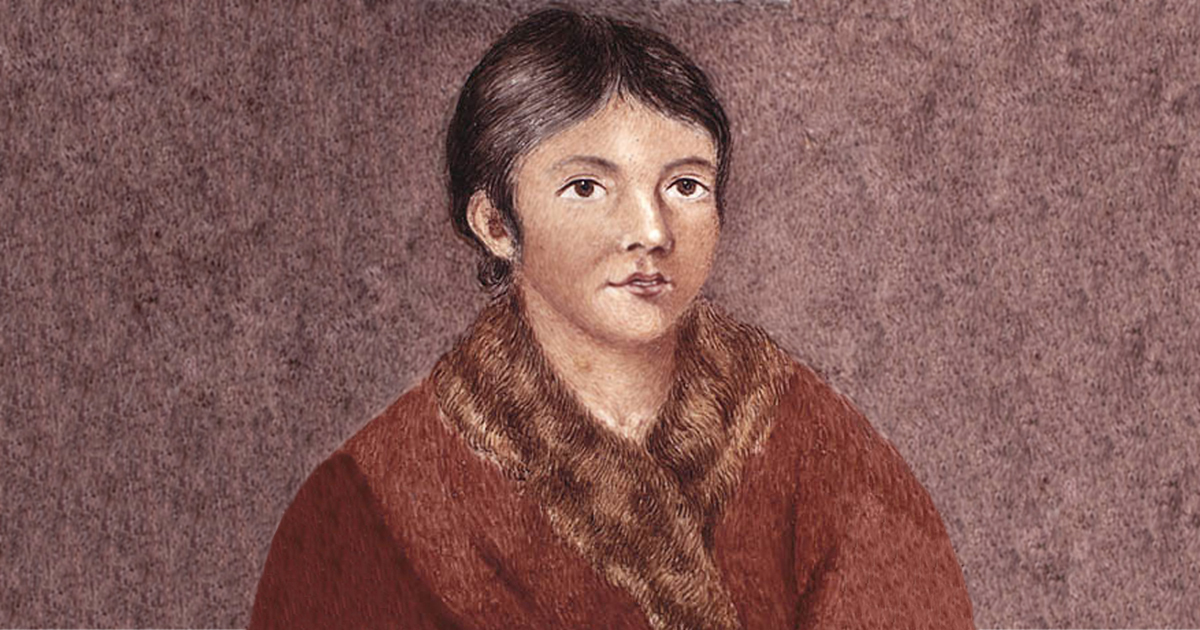

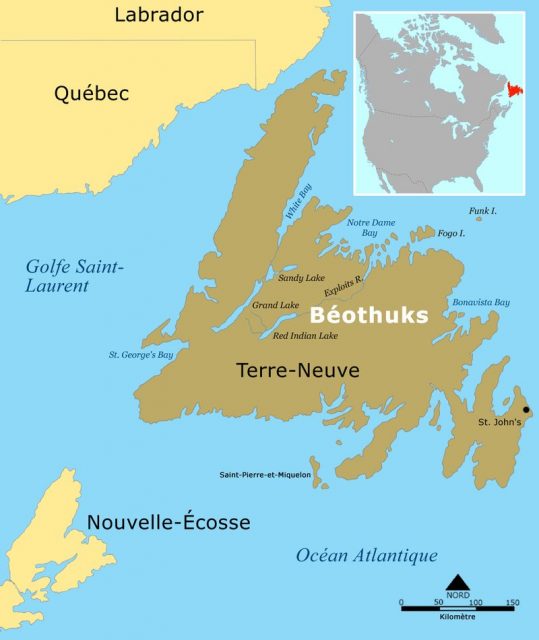

DNA of the Beothuk tribe, thought to have been extinct for nearly 200 years, has remarkably been found in a Tennessee man. For two thousand years, long before Europeans landed at Newfoundland, the indigenous peoples who populated the island included the Beothuk, presumed to be an Algonquian speaking people. As Europeans encroached, their numbers declined rapidly to the point of extinction about two hundred years ago. The last living member of the tribe was Shanawdithit who died of tuberculosis in St. John’s, Newfoundland in 1829. Surprisingly, now DNA from the Beothuk tribe have been found in a man living in Tennessee.

Dr. Steven Carr, a professor of biology at Memorial University in Newfoundland, is conducting a study to find out what happened to the Beothuk. According to Live Science, he says that some people in Newfoundland claim to be descendants of the tribe but have no factual proof. Using previous research completed in 2017 by Ana Duggan, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Anthropology at McMaster University in Ontario, and her colleagues, Carr looked at the mitochondrial DNA passed down by mothers that was harvested from the bones of eighteen Beothuk including the aunt and uncle of Shanawdithit.

He compared it with mitochondrial DNA in the database of the National Institute of Health, GenBank, and contacted the man in Tennessee who has been researching his genealogy. The man was not aware of any links to Newfoundland Indians but intends to double down on his research.

Another early tribe of Newfoundland and Labrador, the Maritime Archaic, overlapped with the Beothuk. Carr found the DNA relationship to be very distant, but they do share an ancestor, the oldest known Maritime Archaic found, a twelve-year-old boy who died in southern Labrador about eight thousand years ago who has DNA that is similar to the Beothuk. Carr also discovered that both of these peoples share ancestry with the Canadian Ojibwe.

The Mi’kmaq, an ancient tribe that survives today mainly in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island as well as the U.S. states of Maine and Massachusetts, have taken an interest in Dr. Carr’s work. Dr. Chief Mi’sel Joe has always believed that the Mi’kmaq and the Beothuk intermarried, and he wanted to prove his theory. Because there is not enough Mi’kmaq DNA in GenBank, Carr is working closely with the tribe, testing over two hundred individuals in a project funded by National Geographic Explorer.

The Canadian Encyclopedia says that when Europeans arrived in Newfoundland there were about five hundred to one thousand Beothuks living on the south and northeast coast. They subsisted on seals, sea birds, and fish and carved canoes from trees. Shanawdithit revealed that her people believed in the spirit world with a Creator and dark spirits paralleling the Christian God and Devil. The Beothuk’s language may have been related to the Algonquian language family, but is now extinct.

They lived in bark or skin covered wigwams in the warm months and retreated to partially underground houses in the winter. In the 1600s, European fishermen began staying in temporary campsites along the coast in the summer, and when they left, the Beothuk were able to retrieve tools and other metal objects which they would fashion into something useful to them. In the 1700s, when the Europeans began to establish permanent settlements, the tribe was forced to move inland to avoid the new strangers.

The move totally disrupted the Beothuk’s way of life. They were exposed to diseases carried by the Europeans which devastated the population. They did not have the same access to food and shelter as before and slowly died out.

In 2007, the Canadian government unveiled a Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada plaque honoring Shawnadithit and her importance to the history of Canada. Her stories have done much to educate Canadians about their native history. In March of 1819, she watched as Europeans kidnapped her aunt, Demasduwit, and do away with her uncle, Chief Nonosbawsut.

Related Article: Supreme Court Rules Half of Oklahoma Belongs to Native Americans

The burial items and skulls were taken by Scottish explorer William E. Cormack who sent them to Robert Jameson at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. The bones were kept there until Mi’kmaq Chief, Mi’sel Joe, petitioned the government to return the bones to their country of origin which was done in March of 2020.