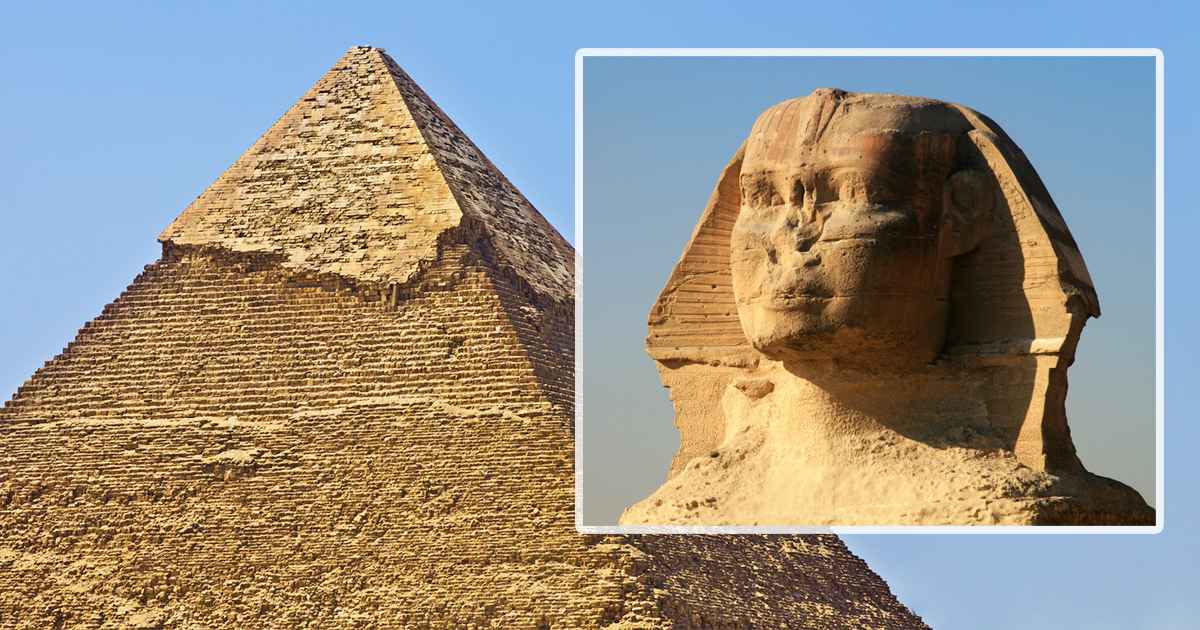

The ancient pyramids of Egypt have long been a source of wonder and fascination to tourists and archaeologists alike.

One of the most compelling mysteries about them is how they were constructed, and of course what they contain.

After all, the pyramid in the Giza Plateau, for example, was built 4,500 years ago, long before the invention of backhoes and cranes and other modern construction equipment. The techniques used are still largely a mystery, confounding archaeologists and other experts.

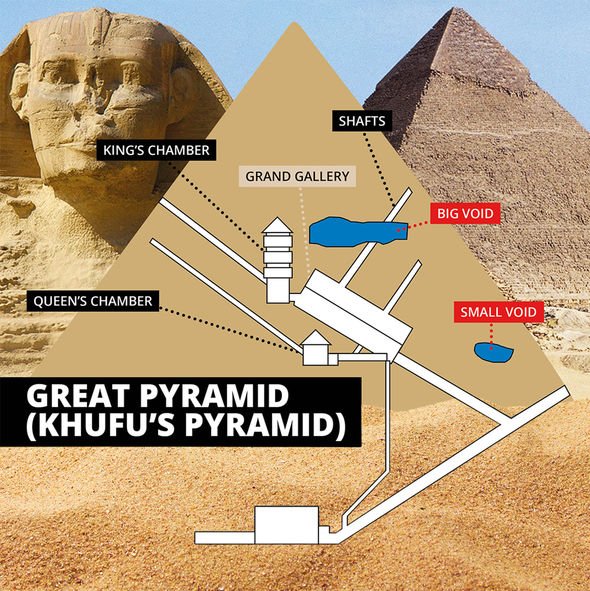

But thanks to the Scan Pyramid Project, what rests inside the Great Pyramid of Giza is better understood. (The body of Pharaoh Khufu, for whom the pyramid was built, has not been discovered, and nor do archaeologists expect it ever will be.)

The project was begun about five years ago, but it was three years ago, when the “Big Void,” as it is called, was found, there was much anticipation and excitement about what future revelations might be forthcoming.

Alas, nothing new or important has been found, leaving archaeologists to wonder whether work on the project has stopped completely. The “Big Void” refers to 30 metres of empty space located just above the Grand Gallery.

Dr. Chris Naunton, an archaeologist and expert on the Great Giza Pyramid, recently told the press that, although the discovery of the “Big Void” was thrilling at the time, in 2017, little progress has been announced since then.

He believes that, because archaeologists cannot go inside the structure, little more can be found at the site, including any remains of the Pharaoh. Any attempt to enter the pyramid would naturally cause damage, and that, of course, will never be allowed by officials at the Ministry of Antiquities in Cairo.

“I can’t see much possibility,” Naunton told the express.uk, “that new information will come from the pyramid itself.” He added that areas around the pyramid have undergone excavation, and are as thoroughly explored as they can be, at least for the moment.

Even those sections that remain unexplored, Naunton continued, may not reveal a lot of new insights into the contents of the structure.

Unlike digs at the Valley of the Kings, a tomb cannot just be entered whenever archaeologists wish; there are many rules and regulations governing access, and even attempting to enter it could lead to significant damage, Naunton explained.

He has considered proposing that a fibre optic camera accessing inside the Great Pyramid of Giza might reveal a lot without causing problems, but he thinks it’s unlikely that the Egyptian government would agree to even that.

Archaeologists have for years been reluctant to request permission to work at the pyramid, in part because navigating the restrictions is so difficult.

It would take a very long time to complete and submit the necessary paperwork, Naunton said, and most experts fear the Ministry would probably turn down any and all proposals.

The Egyptian people are, justifiably, very protective of the Great Pyramid of Giza, and Naunton believes there would be a huge public backlash if archaeologists were allowed to enter it, even with a camera through a wall.

There are more than 110 other pyramids in Egypt, built as tombs for rulers and sometimes their family members. In the meantime, he and others in his field content themselves with other fascinating areas of Egypt that provide many opportunities for advancing public knowledge of the imposing structures.

In the Valley of the Kings, he said, “there is lots of gold and lots of excitement,” and no risk of harm coming to such a profoundly important part of Egyptian history.

Another Article From Us: Ekranoplan: The Only Lun Ever Built, Lies Stranded in the Caspian Sea

That is the kind of excavation that is amendable to both sides – those who are anxious to explore ancient Egypt, and those who are anxious to preserve it.