The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we go about a lot of things, including education. While waiting for the approval of vaccines to combat the virus, school boards were forced to adopt distance learning practices to ensure the safety of students and teachers.

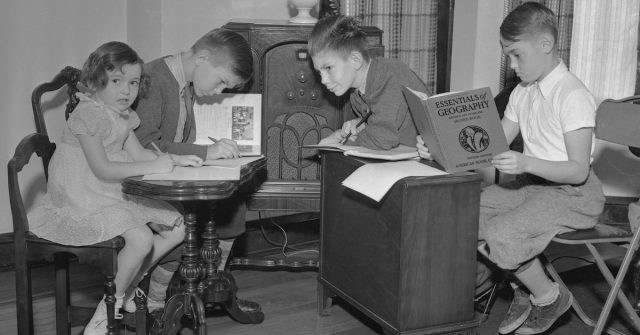

What many might know is that educational institutions have utilized remote learning on and off for years. One of the more interesting times was in 1937, when students in Chicago spent three weeks at home, learning lessons over the radio.

Polio in America

The polio epidemic ran rampant throughout America until the development of a vaccine in 1955. U.S. cities frequently saw devastating outbreaks, with those afflicted often young and at high risk of becoming crippled or paralyzed.

Such an outbreak occurred in Chicago during the summer of 1937, impacting the start of the school year. In the first 28 days of August, the city’s Board of Health recorded 98 cases, resulting in the closure of pools, parks, and other areas often populated by children.

The decision to postpone the start of in-class learning at city schools was made after the Board of Health consulted with the mayor and city council. As the first day of school neared, a statement was released, reading: “the opening of all schools in the city of Chicago be delayed until such time as the Board of Health advises that it is safe for the schools to open.”

Thus, students and their parents were thrust into the throws of remote learning.

Distance learning via radio

It was decided students would learn from home by listening to lessons played over local radio stations, including WENR, WGN, WSL, WIND, WJJD, and WCFL. Lessons were permitted to air between 7:15 a.m. and 11:45 a.m., Monday to Saturday. Daily schedules were posted in newspapers, which allowed students to know when their lessons were and on what station they needed to tune in to.

Subjects were split between the days of the week. Students could expect to learn science and social studies on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays, while Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays were reserved for English and math. Each school day began with on-air announcements and gym class.

The objective of the project was to blend the importance of education with the entertainment of radio; it needed to be “entertaining while informative.” Teacher instruction was short, totaling 15 minutes, and provided basic instruction and homework assignments. Afterward, two school principals would provide feedback on the articulation, the content, the teachers’ vocabulary, and their overall performance.

The school boards also wanted parent and community involvement. It assigned 16 teachers to man the phones at the district’s central office, where parents could call in. That total was later increased by five, as the first day saw over 1,000 calls logged.

There were some hiccups

As with distance learning today, students and parents found flaws with the radio experience, despite news outlets from the time reporting on it fairly positively.

Many found teachers spoke too quickly, making it difficult for them to write down instructions. Being stuck at home also created issues, as kids were easily distracted without the authority of the classroom.

Parents found they had to step in for teachers a lot of the time. Students were unable to directly ask their teachers for help, which meant parents had to fill in the gaps.

This drastically hurt the learning of those in need of that extra assistance, and many educators expressed worry that “the pupils who benefit by the radio lessons” were likely “those who need them least” and “who would suffer least by curtailment of their classroom instruction.”

The biggest hurdle was that not every household owned a radio and that those who did were sometimes unable to tune them to the right stations. This created an educational gap that needed rectifying upon in-class learning starting up again. This saw schools create make-up work for those who had fallen behind.

Children head back to school

After three weeks, Chicago’s schoolchildren were allowed back in school, with public school superintendent William H. Johnson stating that around 315,000 had tuned in to the radio broadcasts since mid-September.

The advent of the program helped transform educational radio in Chicago. The partnership between the school board and the city’s radio stations resulted in the creation of the Chicago Radio Council.

The council produced educational shows aimed at supplementing grade-level curriculum, and it worked to bring radios into the classroom. This meant teachers could incorporate on-air programming in their lessons and get students interested in the broadcasting industry.

More from us: When Smallpox Scars Were Used As Makeshift ‘Vaccine Passports’

The amount of educational programming on-air began to dwindle toward the start of the new decade. By 1945, the board’s own station, WBEZ, was the only one airing educational content.

Despite the decline, the spread of such programming on radio showed distance learning’s lasting effect on the city and the continued education of students.