Did Cleve Cartmill’s sci-fi short story “Deadline” expose details of the Manhattan Project a year before its explosive conclusion?

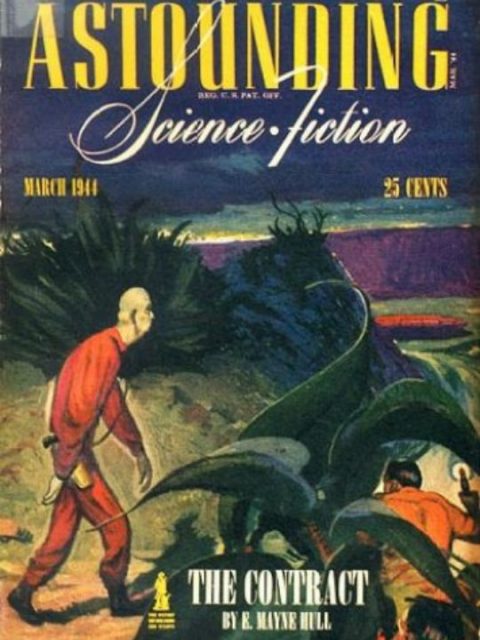

Authorities certainly thought so, with the FBI reportedly dispatched to investigate author Cleve Cartmill and Astounding Science-Fiction editor John W Campbell Jr. following publication in March 1944.

Science fiction can sometimes predict future events. “Deadline,” however seemed a little too on the nose. So, how did the story come about?

“Deadline” was a strangely accurate version of events surrounding the atomic bomb

In classic sci-fi style, Cartmill showed readers today’s world through a futuristic lens. As described by Peter Lobner for The Lyncean Group of San Diego, the action focuses on the Seilla and the Sixa — two warring powers seeking to detonate “the Bomb.”

These are apparently connected to the Allies and Axis forces, respectively. World War II was ongoing at the time, with Cartmill barred from combat on medical grounds.

It was Cartmill who originally pitched the basic idea to Campbell. The latter then gave Cartmill a raft of material from publicly available science journals.

What are the parallels between Cartmill’s story and The Manhattan Project?

For starters, the technical details presented by Cartmill checked out. Astrophysicist and author Gregory Benford wrote the essay “Old Legends” about science fiction’s influence on atomic research. Speaking to Edward Teller — theoretical physicist and pivotal figure in the Project — he notes that the content of “Deadline” was “remarkable, its sentiments even more so.”

This emotional aspect got officials’ minds racing. Ultimately, the Seilla forces decide not to push the button and trigger a conflict-ending cataclysm. Did readers agree with their actions?

Benford pondered whether “Deadline” might “hint at what the American public really thought about such a superweapon, or would think if they only knew?”

He also draws attention to the Allied group of scientists working on the Manhattan Project, who could have recognized themselves in the characters, and their speculation over what impact the Bomb would make on the world.

Fat Man and Little Boy

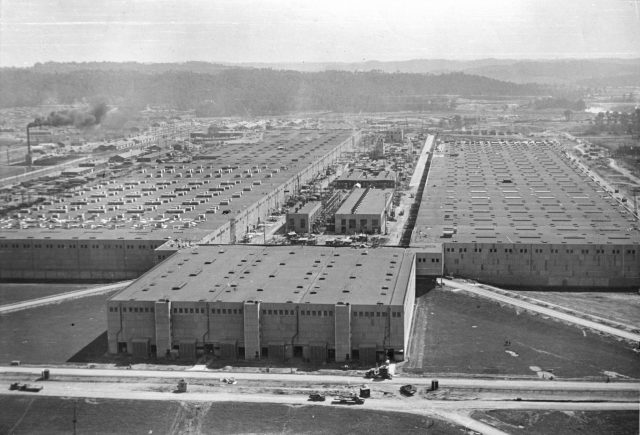

The roots of the Manhattan Project lie in the years before America got involved in WWII. A more accurate name for it may be The Los Alamos Project — this New Mexico town was where the majority of the work took place.

History details how the idea of an American atomic bomb crystalized. With reports coming in of a German-made nuclear weapon potentially wielded by Hitler, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began assembling a rival team in 1939.

What started as the Advisory Committee on Uranium became the OSRD (Office of Scientific Research and Development). The devastating attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 drew Roosevelt into the war. Things stepped up a few gears.

The OSRD met the Army Corps of Engineers. History writes the Project, locating itself in Manhattan, “officially morphed into a military initiative, with scientists serving in a supporting role.”

Two bombs were developed and given the names Fat Man and Little Boy. The first used plutonium and the other uranium. Both went on to decimate the Japanese cities of Nagasaki and Hiroshima respectively. Over 100,000 people lost their lives on the ground.

The movie Fat Man and Little Boy was released in 1989. It starred Paul Newman as Manhattan Project director Leslie Groves and Dwight Schultz (The A Team) as Professor J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Destructive capability aside, History goes on to say that today’s nuclear power plants, MRI scanners and more wouldn’t exist without the Manhattan Project’s research.

What happened to Cartmill and Campbell?

While the FBI and others were deeply concerned over “Deadline,” the author and editor ended up in the clear.

As mentioned by The Lyncean Group, a report was written on the matter by Albert Berger for Astounding Science-Fiction. Titled “The Astounding Investigation: The Manhattan Project’s Confrontation With Science-Fiction,” it highlighted examples of earlier stories where atomic weaponry was mentioned.

Berger’s report states that such imaginary tales possibly generated “unwanted public speculation” in government operations. However, they also “might help people working in compartmented classified programs to get a better understanding of the broader context.”

Is Cleve Cartmill’s “Deadline” a science fiction classic?

Perhaps the most interesting thing about “Deadline” is the lack of good reviews. Even Cartmill didn’t like the story, according to A Requiem For Astounding by Alva Rogers.

It’s worth mentioning the author is known chiefly for “Deadline,” but he also contributed to the field of typography by co-inventing the Blackmill system.

Meanwhile, Campbell reportedly twigged something was up down in Los Alamos through an unlikely source — Astounding Science-Fiction’s brainy subscriber base. The editor was sending an awful lot of magazines to New Mexico. He figured they acted on a rather sizeable hunch and relocated there.

More from us: Morse Code Facts That Made Us Stop And Think

The Science-Fiction Encyclopedia writes that “Deadline” was “a prime exhibit in the arguments about prediction in SF.”

This boundary-defying genre has a habit of commenting on and foreshadowing world events. It seems Cartmill wasn’t engaged in espionage. He merely drew his own intriguing conclusions.