Morse code was a groundbreaking development in its day. Not only did it have its place in wars and trade, but it was also used to send personal messages and to try and prove the existence of the afterlife. It was one of the crucial steps in creating the technology we take for granted today.

Here are some fun facts about Morse code at its influence on our modern-day life.

Inspired by a tragic event

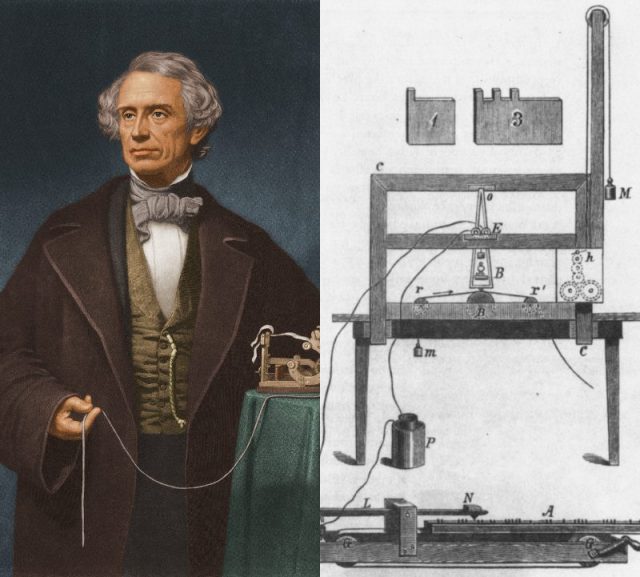

Morse code was invented by Samuel FB Morse. Samuel was a gifted painter and inventor. He came up with the idea after he received a horse messenger informing him that his wife was ill. The message had taken so long to reach him that by the time he came home, she’d not only passed away but had already been buried.

After seeing electromagnetic experiments, Morse and his assistant Alfred Lewis Vail set about creating an electromagnet machine that would respond to an electric current sent along wires. The first message they transmitted read: “A patient waiter is no loser.”

The first long-distance telegraph test was conducted on May 24, 1844. Standing before government officials, Samuel (who was in Washington, DC) sent a message to Alfred (who was in Baltimore). An onlooker suggested “What hath God Wrought?” as the message. The words traveled 40 miles before they were recorded on paper tape.

Samuel’s invention had the desired effect: messages could be received in minutes rather than days, and the Pony Express officially ceased operation in 1861 after the telegraph and Morse code became the more popular communication method.

Morse code today doesn’t really resemble what Morse invented

Morse code assigned short and long signals to letters, numbers, punctuation, and special characters. Samuel’s own code initially only transmitted numbers. It was Alfred who added the ability to communicate letters and special characters. He spent time examining how frequently each letter was used in the English language. Then he assigned the shortest marks to the most common ones.

Since this code was started in America, the first code was known as American Morse code or Railroad Morse since the railroads used it widely. Over time, the code was simplified further by others (such as Friederich Clemens Gerke) to be more user-friendly. Eventually, an International Morse Code was created in 1865. It has been adapted to create a Japanese version called Wabun code and a Korean one called SKATS (Standard Korean Alphabet Transliteracy System).

Morse code is not a language but can be spoken

Crucially, Morse code is not a language because it is used to encode existing languages for transmission.

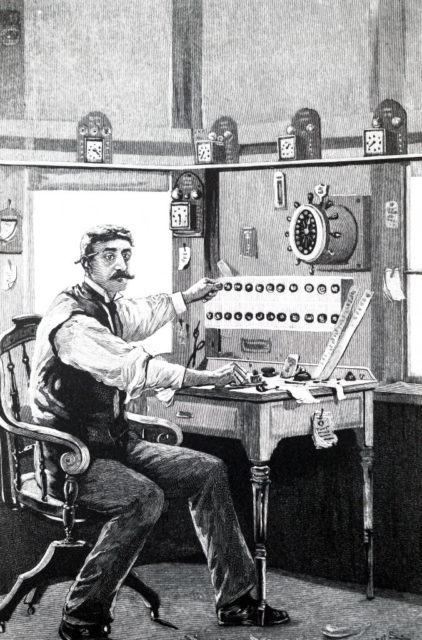

Originally, the electrical impulses would arrive at a machine that would make indentations on a piece of paper, which an operator would read and transcribe into words. However, the machine made different noises when it marked a dot or a dash, and the telegraph operators began to translate the clicks into dots and dashes just by listening to them and writing it down by hand.

After that, information was sent as an audible code. When the operators were talking about messages received, they would use “di” or “dit” to describe a dot and “dah” for a dash, creating yet another new method for transmitting Morse code. Skilled operators could listen to and understand code at a rate in excess of 40 words per minute.

SOS was created specifically for Morse code

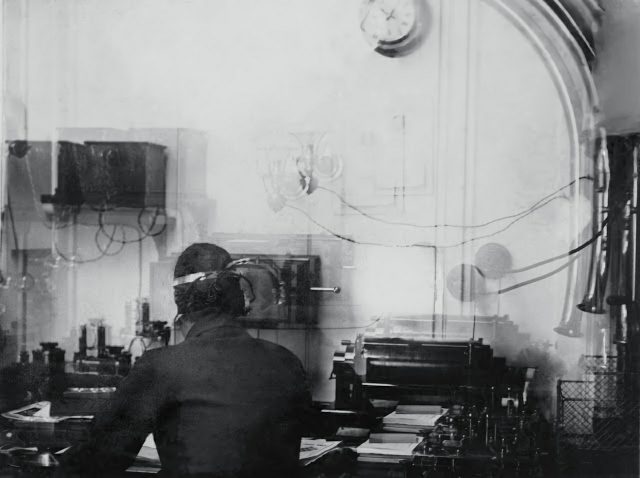

Guglielmo Marconi set up the Wireless Telegraph and Signal Co. Ltd in 1897. He’d noticed that ships and lighthouses needed to communicate swiftly but didn’t have access to the cable network, so his wireless technology was designed to appeal to them. By the early 1900s, telegraphy was widely used on ships.

It was decided that it would be a good idea to have an international distress signal to help rescue ships. The International Radiotelegraphic Convention decided in 1906 that “SOS” was the best choice because it was quite simple: three dots, three dashes, three dots.

Once it was adopted, some people suggested that this combination of letters had been chosen because it stood for “save our souls” or “save our ship,” but in fact, it was chosen because it was simple to remember and easy to recognize.

Morse code saved lives aboard the Titanic

In April 1912, more than 1,500 of 2,224 passengers on the Titanic perished when the ship sank. Those who survived owed their lives in part to Morse code, which had been used to alert the Cunard liner Carpathia as to the Titanic’s final position and fate.

By the time the Titanic set sail, most passenger ships in the North Atlantic had a Morse code installation, run by those trained by Marconi’s company.

At the time, it was quite fashionable for passengers to ask the Marconi operators to send personal messages on their behalf. With no dedicated emergency frequency, this meant that the channels were jammed with passenger messages, and so the Titanic’s distress call was diluted, going unheard by some ships.

However, the message was received by Harold Cottam on the Carpathia, and the ship changed course and traveled for four hours to offer assistance.

Eagle-eyed viewers of the 1997 movie Titanic might notice that the captain instructs the senior wireless operator Jack Phillips to send the distress call “CQD.” This set of letters had been adopted by the Marconi Company before the 1908 decision settled on SOS, and these letters were still used by some ships post-1908.

Interestingly, a deleted scene from the movie shows that after the captain leaves, Harold Bride (the assistant operator) says to Phillips: “Send SOS. It’s the new call, and it may be your last chance to send it.” This is in reference to a real conversation that occurred between the two men.

Morse code as inspiration in music

Morse code has very definitely been incorporated into some songs. At the end of London Calling by The Clash, Mick Jones plays a string of Morse code on his guitar, the rhythm being SOS. Kraftwerk’s single Radioactivity contains two instances of “radioactivity” being spelled out using Morse code.

Perhaps the most famous inclusion of Morse code into music was Better Days by Natalia Gutierrez Y Angelo. This song was created specifically to contain a Morse code message to soldiers being held by The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. The message read: “19 people rescued. You are next. Don’t lose hope.” Many prisoners later confirmed that they’d heard the message and either escaped or were rescued.

A last cry before eternal silence

As technology advanced, Morse code was left behind. When the French Navy officially ceased using it on January 31, 1997, they chose a poignant farewell as their final message: “Calling all. This is our last cry before our eternal silence.”

The final commercial Morse code message was sent in the United States on July 12, 1999, from the Globe Wireless master station near San Francisco. The operator signed off with Morse’s original message of “What hath God wrought?” followed with a special sign that means “end of contact.”

While Morse code is not widely used today, that doesn’t mean it isn’t helpful in some areas. Amateur radio operators continue to use it, and it can be especially useful to know as a method of communicating in an emergency when more sophisticated means of communication fail. For example, it can be used by tapping your fingers, flashing a torch, or blinking your eyes. For ships, using signal lamps with Morse code can be a way to allow communication during radio silence.

More from us: A Year After the Titanic Tragedy, a Mourning Family Received This Chilling Letter

Even though knowledge of Morse code today is more often acquired as a fun skill or a hobby, there can be no denying the influence that telegraphy and Morse code had on the history of technology.