It’s only July, and people are already speculating as to which celebrities will be taking to the dance floor for 2021’s series of Strictly Come Dancing. Add to that Dancing on Ice and all the other shows that feature fancy footwork, and you’ve got a nation fascinated by dancing.

But there was a time when dancing had another, deadlier side to it.

The Dancing Plague

In Europe, from the 14th to the 17th century, there were various outbreaks of “choreomania.” The term is taken from the Greek word “choros” meaning dance and “mania” meaning madness, although the noted physician and philosopher Paracelsus coined the term “dancing plague.” During outbreaks of dancing plague, people would dance for hours, days, weeks, or even months. Once people started dancing, they couldn’t stop themselves and would fall into a kind of daze or trance.

Sometimes musicians joined them, hoping that their music would soothe the disease. But, perhaps unsurprisingly, all it did was encourage other people to join in the dancing. There was no pattern or distinction to who might be affected – it could strike strangers or locals. The dancers might make their from village to village, picking up more people on the way.

In fact, in 1237, a large group of children danced 12 miles from Erfurt to Arnstadt in Germany. It was around this time that the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin originated, leading some to believe the dancing event could have inspired the legend.

Distinguishing features

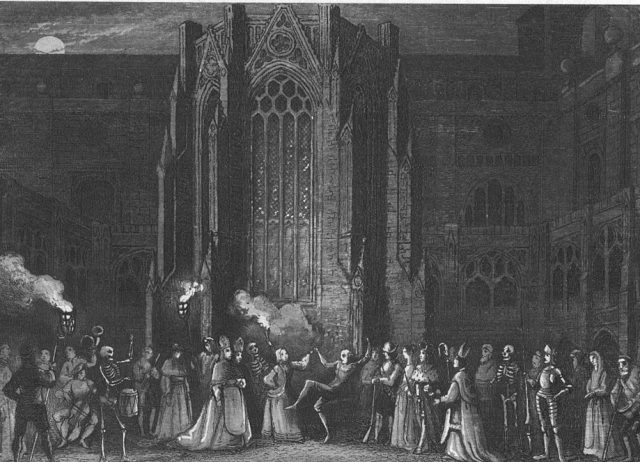

viPhoto Credit: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsSome dances would simply be confusing and exhausting, while others were described by onlookers as bizarre. The dancers might parade around naked, make obscene gestures, or act like animals; they would scream, laugh, cry, and sing. One source notes how dancers would become violent if they encountered the color red.

Such prolonged dancing brought with it a raft of medical conditions: chest pains, convulsions, hallucinations, hyperventilation, and visions. In extreme cases, the dancing could result in death, either through exhaustion, heatstroke, heart attack, or because a participant broke their ribs while leaping about.

It was clear that the people dancing were doing so unwillingly. There are many reports of dancers begging churchmen to bless them and release them from the curse, writhing in pain, and screaming for help.

A curse from Heaven

Without detailed knowledge of medicine, the popular opinion was that the plagues were a curse from a saint. This belief was bolstered by the fact that many of the outbreaks occurred around St Vitus’s feast day. Some referred to the disease as St Vitus’s Dance or St John’s Dance, believing that one of them had cursed the people. As a result, priests and non-affected members of society would try and guide the dancers to the relevant shrine so that they could offer prayers and petitions for the curse to be lifted.

In the 17th century, Gregor Horst, a professor of medicine, wrote about how the phenomenon seemed intimately connected with St. Vitus in particular. “Several women who annually visit the chapel of St. Vitus in Drefelhausen… dance madly all day and all night until they collapse in ecstasy. In this way, they come to themselves again and feel little or nothing until next May, when they are again… forced around St. Vitus’s Day to betake themselves to that place.” He added how one woman had been doing this for 20 years, another for 32 years.

The saints weren’t the only supernatural beings to be blamed. There was some belief that those dancing were possessed by a demon, so they were isolated and exorcisms were performed.

One account states that on Christmas Eve in 1021, 18 people began dancing outside the church in the German town of Kölbigk. Furious at their refusal to stop, the priest cursed them to dance for a whole year without respite, which they did, before falling down dead.

What was the real cause of such plagues?

Even today, it’s still unclear whether this was a genuine illness or some kind of social phenomenon. Over the years, various theories have been put forward.

A popular theory is that it could have been ergot poisoning. Ergot is a fungus that grows on rye and other crops during damp periods. Ingesting it can cause hallucinations and convulsions, but not some of the other symptoms seen in choreomania.

Similarly, encephalitis, epilepsy, and typhus have all been advanced as possible causes, but as with ergot poisoning, no one disease can account for all the symptoms occurring in the dancers.

Sydenham’s chorea is an autoimmune disease characterized by rapid, uncoordinated movements of the hands, face, and feet that can make the patient look like they’re writhing. The disease can result from a childhood infection of Streptococcus and is sometimes called St. Vitus Dance. With proper treatment, the symptoms can settle within 2-3 months.

However, there is also the possibility that choreomania was a social phenomenon rather than an illness, as a well-documented incident in Strasbourg suggests.

What the 1518 Strasbourg incident can teach us

The most famous incident of choreomania occurred from July to September 1518 in the city of Strasbourg (now located in modern-day France). Plenty of contemporary evidence in the form of physician’s notes, including those of Paracelsus, cathedral sermons, and council notices means that researchers can put together a clearer picture of what happened.

It all started with one woman (possibly named Frau Troffea) dancing in the street, and ended up with somewhere between 50 to 400 people being drawn in. While some later sources claim around 15 people a day perished due to the intense summer heat, no contemporaneous records mention deaths or fatalities.

Having researched the Strasbourg incident, historian John Waller wrote in The Lancet in 2009 that he couldn’t imagine ergot being the cause of the dancing because it would not cause dancing for days at a time and wouldn’t have affected people in precisely the same way. Instead, he argued that it was an early case of mass psychogenic illness.

He believes the “involuntary trance state” of the dancers was more likely due to the “high levels of psychological stress” that the people suffered after “a succession of appalling harvests, the highest grain prices for over a generation, the advent of syphilis, and the recurrence of such old killers as leprosy and the plague. Even by the grueling standards of the Middle Ages, these were bitterly harsh yeas for the people of Alsace.”

Another factor is that the people in the Rhine and Moselle valleys shared a fear of wrathful spirits that could inflict such a curse. There was also a legend that St. Vitus had placed a dancing curse on a nearby location. Waller comments that “people are more likely to enter the trance state if they expect it to happen.”

The authorities in Strasbourg didn’t help themselves, either. Believing that the dancers suffered from overheated blood and needed to dance the curse out of their system, they not only hired musicians and professional dancers to keep the dance going, they also constructed a special stage for the afflicted. Such a public show was naturally going to draw in more participants.

More From Us: Meowing nuns, biting frenzy, dancing mania, and marauding Irishmen: weird cases of mass hysteria

For John Waller, these curious incidents of dancing plague should be a reminder that “the symptoms of mental illness are not fixed and unchanging” but can be influenced by society and external pressures. The dancing mania phenomenon “reveals the extremes to which fear and supernaturalism can lead us,” providing us with important lessons from history.