People living in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of Washington D.C. may not know there are secret tunnels under their feet. These came to light in the early 20th century and a number of theories were offered over what purpose they served.

The answer turned out to be a little unexpected. Read on to find out the secret that quite literally lay buried for years.

The first discovery

Americans first heard about a hidden tunnel in 1917. A building development that became the old Pelham Courts apartments led to the first discovery.

As covered in the press, laborers found a brick tunnel measuring 22 feet all the way around. So far, so intriguing. But sadly, the mystery would have to wait. The Architect of the Capital website mentions one or two things going on in the world at the time that took the heat out of the story.

They write that “only a month earlier, the U.S. had officially entered World War I, and the Selective Service Act was passed just the day before the article was published.” In other words, it was time for the public to be conscripted into combat.

Events moved on and the tunnel stayed put, where it was seemingly forgotten about.

That sinking feeling

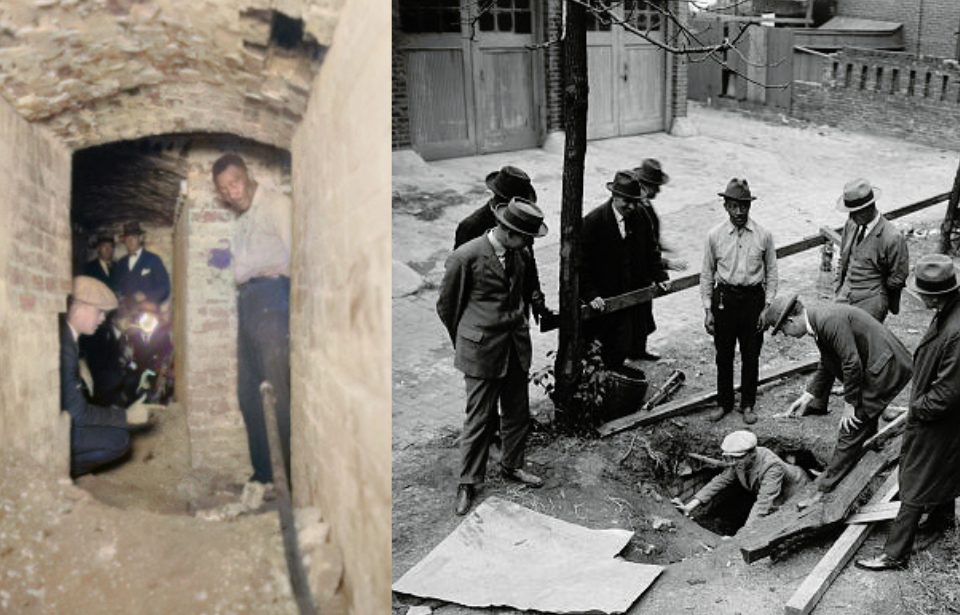

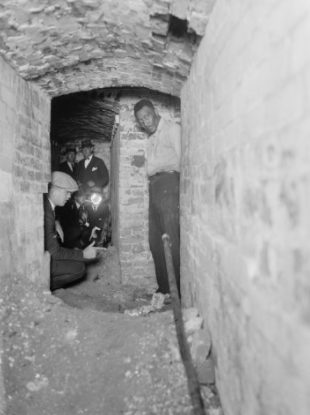

Flash forward to 1924. What appeared to be an underground network was discovered in a far more dramatic way. This time, a truck drove over a weak spot at Pelham Courts. It accidentally exposed what the Washington Post describes as “an elaborate, multilevel tunnel.”

Investigators reportedly entered a small but perfectly formed space with standing room. It was constructed from an expensive brick made of white enamel. With electric lighting installed, this was clearly a substantial project for whoever completed it.

What drew a lot of attention were the ceiling decorations. Or rather, German newspapers dated 1917-18. Architect of the Capital highlights coverage from the Post, which notes the papers had head-scratching ciphers added to them.

What were the mystery tunnels?

Immediately, a picture of wartime intrigue formed in reporters’ and readers’ minds. But which war? The First World War? The Civil War? No one quite knew how long the tunnels had been down there.

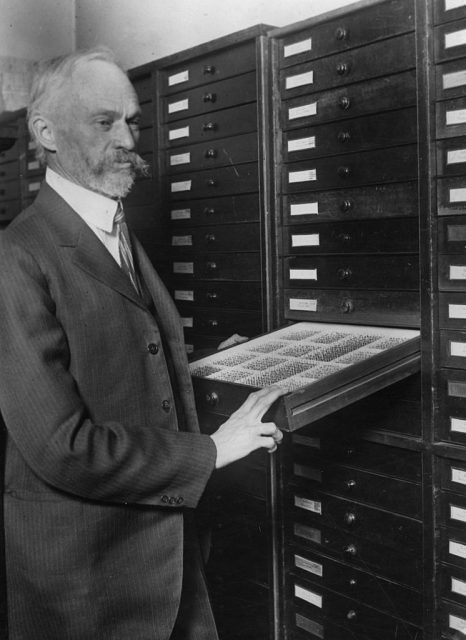

Eventually, the mastermind behind the network was revealed. He wasn’t a superspy… he was an entomologist. A bug expert to me and you.

The man responsible

Harrison G. Dyar Jr. worked for the world-famous Smithsonian Institute. A clever fellow indeed to secure a position at such a prestigious workplace. And what he got up to in his spare time suggested a restless, and possibly compulsive, nature.

His interest in tunnels started small. In fact, Dyar was digging a flowerbed when he was bitten by the bug, so to speak. In an interview with the Washington Star, he claimed he was “seized by an undeniable fancy to keep on going.”

As well as the tunnel under Pelham Courts, Dyar toiled away on a network some 24 feet deep elsewhere, according to the Post. For the eminent mosquito expert, this was a hobby, something he did at home. Specifically, under it.

“The ceilings were arched, like some medieval catacomb,” the Post writes about the second tunnel system. “In places Dyar had sculpted the heads of animals and humans.”

He couldn’t explain the German papers. Apparently, he wasn’t in the area when they were applied. So who was using the tunnels in his reported absence? To date, that remains a total mystery.

Harrison G. Dyar’s legacy

As an entomologist above ground, Dyar “furthered the understanding of the elusive role of larval stages in taxonomic classification,” according to Smithsonian Magazine. We won’t bug you with the details but he lent his name to Dyar’s Law, a standard way of measuring insect lifestyles, using larvae head size as a guide.

The Magazine also refers to his prolific output, whether naming species or collecting stats on thousands of creepy crawlies. They report on Marc Epstein’s 2016 book about Dyar, Moths, Myths and Mosquitoes.

More from us: Bored Man on Lockdown Finds Secret Tunnel Filled with Old Relics Under his House

He wasn’t the most stable of people by the sounds of things. Not only was he known for getting into confrontations with his peers, he also had more than one wife. One of the wilder theories has him building the tunnels as a way of sneaking between households!