During the Cold War, the United States worked on a plethora of secret, and often eccentric, plans designed to combat Soviet technological advances. The best known of these is President Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars Program, which would use space lasers to defend against nuclear attack. An entirely different plan was underway years earlier, however, one that would have seen the US detonate a nuclear bomb on the Moon.

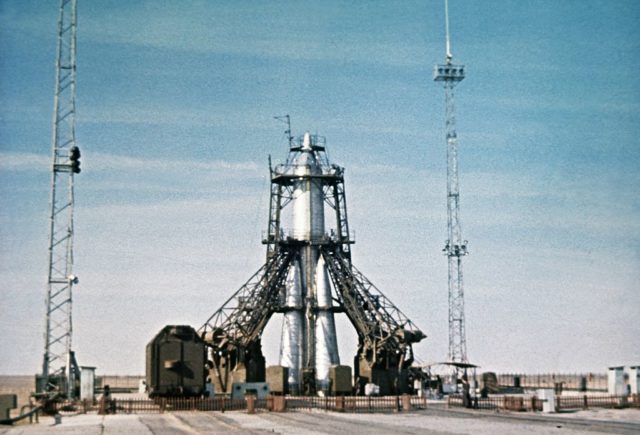

Sputnik launch

By the late 1950s, the space race between the Americans and the Soviets had reached a peak, culminating in the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957. This changed everything, as this was the world’s first satellite and showed the US that the USSR was able to come up with great technological innovations before they were. What was arguably more concerning than Sputnik, was that the satellite had been launched into space on a ballistic missile.

This opened up a whole host of new problems if the Soviets were able to put weapons of that kind into space. In response to the perceived threat, the Americans decided to launch Project A119. In an effort to prove that they were actually the military superior power, the plan was to detonate a nuclear bomb on the Moon and create a mushroom cloud that could be seen from anywhere on Earth.

Project A119

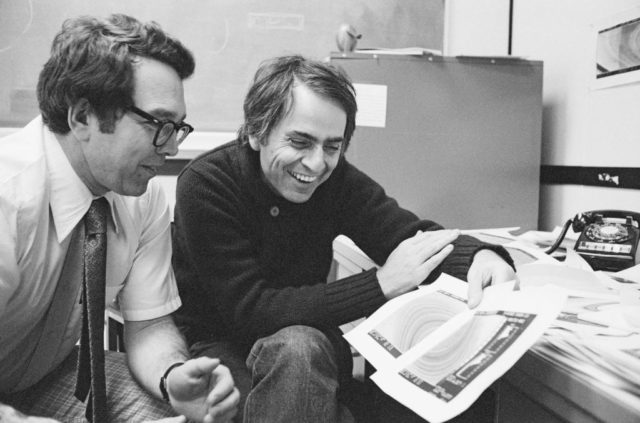

Dr. Leonard Reiffel, known for his work on NASA’s Apollo Program, took the lead on the project. Another contributor was the famous astrophysicist Carl Sagan who was, at the time, a doctoral student working under another researcher assigned to the project. Sagan played a major role in calculating whether the desired mushroom cloud would be seen from Earth.

This prestigious team set to work investigating the feasibility of a bomb being detonated on the Moon, and just how they would get it there. Initially the desire was to use a hydrogen bomb, but this was vetoed by the US Air Force which thought it would be too heavy to propel into space. Instead, they settled on a W25 warhead which was small enough that it could be carried to the far side of the Moon by a rocket.

The final verdict

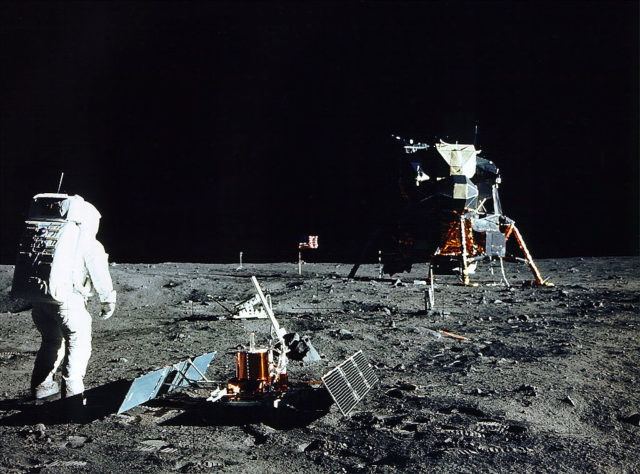

It would explode on impact, and the resulting cloud would be illuminated by the sun. The verdict that Reiffel and his team came to was that a W25 could indeed be launched and landed on the Moon, the explosion could be seen from earth – although not as spectacularly as hoped – and it could have happened in 1959. The project was ultimately canceled in January 1959 due, in part, to concerns over what could happen to the public if something went wrong with the launch.

Another big problem was that it would be extremely costly to undertake the project. There were also scientific concerns that nuclear fallout after the bomb was detonated would prevent further research or colonization of the Moon. Project A119 stayed secret until the 1990s when Keay Davidson, doing research for a book on Carl Sagan, discovered that he had included his involvement in the project on a scholarship application – a dramatic violation of national security.

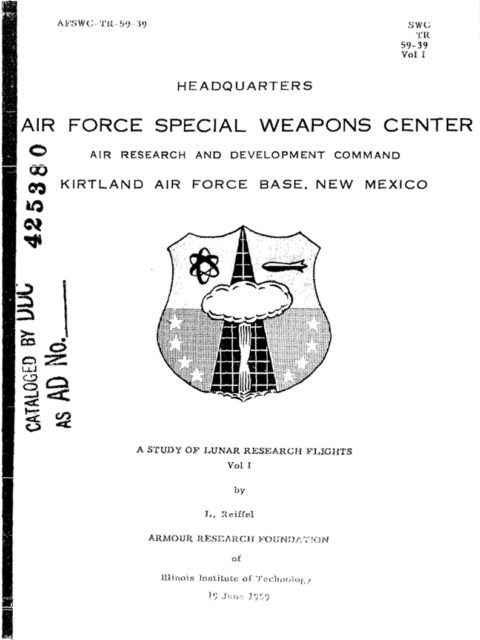

Declassified reports

Soon after the biography was published in 1999, Reiffel also began to speak openly about his experience working on Project A119. By 2000, the final report, A Study of Lunar Research Flights, was declassified. In many interviews, Reiffel spoke about his distaste for the work in the years that followed, saying he was, “horrified that such a gesture to sway public opinion was ever considered.”

He expressed the same opinion while working on the project: “I made it clear at the time there would be a huge cost to science of destroying a pristine lunar environment, but the US Air Force were mainly concerned about how the nuclear explosion would play on earth.”

More from us: What Finally Brought an End to the Cold War?

Fortunately for all, the US never made the plan operational. As one astute scientist of the time phrased it, “You know, we might want to walk up there someday. Maybe we don’t want to blow the hell out of it before we do.”