A massive bronze statue of Hercules, known as Hercules Mastai Righetti, has been housed at the Vatican for years. It shows the half-human Roman god of strength after he finished his labors. The statue is considered divine because it was previously struck by lighting. The restoration team has made a significant discovery about the statue and the people who created it.

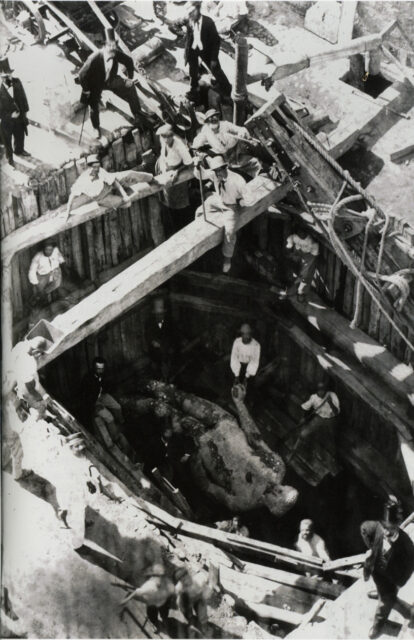

It was found in a banker’s villa

The 13-foot-tall statue of Hercules was originally discovered in 1864 after work had commenced on a banker’s villa close to Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori square. Once the massive statue was identified, it was featured in many newspaper headlines and earned the attention of visitors from all over, including Pope Pius IX. Pope Pius IX later added the statue to the papal collection, where it found its home in a niche of the Vatican Museums’ Round Hall.

Experts haven’t been able to determine the exact date of the statue’s origin, but they’ve narrowed it down between the first and third centuries. For the last 150 years, Hercules Mastai Righetti has gone largely unnoticed by visitors to the museum. Its surface was covered in a dark coating, as well as grime and dust, making it pretty unnoticeable.

An inscription suggests it was struck by lighting

Upon the slab of travertine marble on which the statue stands, the inscription “FCS” is engraved. According to Claudia Valeria, curator of the Vatican Museums’ Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, this indicates that the statue was once struck by lightning.

In Latin, “FCS” stands for “fulgur conditum summanium,” which translates to a phrase meaning, “Here is buried a Summanian thunderbolt.” This inscription was put on objects that were blessed by Summanus, the ancient Roman god of nocturnal thunder.

The ancient Romans believed that objects struck by lightning were imbued with divinity. This blessedness also extended to the place where lightning struck the item as well as to where it was buried. Hercules Mastai Righetti’s burial in a marble shrine helps to support this claim, as it coincides with Roman burial rites that observed lightning as a divine force.

“It is said that sometimes being struck by lightning generates love but also eternity,” Vatican Museums archaeologist Giandomenico Spinola said. The Hercules statue “got his eternity … because having been struck by lightning, it was considered a sacred object.”

The restoration team faced a significant challenge

Vatican restoration of gilded Hercules Mastai Righetti struck by lightning to be completed by Decemberhttps://t.co/hpOZdxYQf6 pic.twitter.com/gBoiOxNXgd

— Sarah (@Sarah404BC) May 14, 2023

During a restoration project intended to remove a wax coating the statue was given during the 19th century, workers discovered that the entire statue was gilded in a beautiful, bright yellow-golden bronze. This means the statue is not only the largest surviving bronze statue of the ancient world but also one of the most significant gilded ones.

Discovery of the gilding revealed the remarkable skill of ancient smelters, who impressively fused mercury to gold. This mixture ultimately made the surface longer-lasting. “The history of this work is told by its gilding. … It is one of the most compact and solid gildings found to date,” says Ulderico Santamaria, a University of Tuscia professor who heads the Vatican Museums’ scientific research lab.

The statue’s burial proved both a benefit and a hindrance to the team in charge of restoring Hercules Mastai Righetti to its former glory. It helped maintain the gilding on the statue over the centuries but also covered it with dirt and build-up that’s proved to be rather difficult to remove.

Painstaking detail that visitors will be able to see

“The only way is to work precisely with special magnifying glasses, removing all the small encrustations one by one,” Vatican Museums restorer Alice Baltera said. After a long, painstaking effort to unveil the statue’s gold surface, the removal of the 19th-century wax coating is finally complete. “The original gilding is exceptionally well-preserved, especially for the consistency and homogeneity.”

The restoration team is now focused on making fresh casts out of resin, intended to replace the plaster patches that were used to cover up missing pieces. These include a part on the nape of the neck as well as the pubis.

More from us: How the ‘Stone of Destiny’ in England’s Coronation Chair Was Once Stolen by Four Students

Visitors will be able to see Hercules in all its grandeur when the restoration is complete, which is expected in December.

Let us know what you think in the comments below!