There once was a plant called silphium that was used as a miracle for all sorts of purposes in ancient Rome. The sap that ran through the plant was like liquid gold, and the Romans made sure to use every single drop. Silphium is believed to have gone extinct due to the Romans’ greedy overuse of the herb. However, a new study suggests that the plant may have survived all this time – just not where it was supposed to.

The Romans used silphium for practically everything

It is believed that silphium first showed up over two and a half millennia ago after a “black” rain covered the eastern coast of modern-day Libya. Confined to a region of only 125 by 35 miles, then known as part of the Greek city of Cyrene, silphium was able to grow there due to the unique climate. Cyrene could experience up to 850 millimeters of rainfall in a calendar year, making it almost as rainy as Ireland and the United Kingdom.

Silphium thus grew rampantly in the area, and once they got their hands on it, this helful herb was practically worshipped by the Romans. The sap from the plant’s stalk was used for medicinal purposes and was able to treat many ailments like nausea, chills, fever, and more.

The plant was also grated and liberally added to dishes to improve the flavor of food. It was eaten by the Romans, fed to sheep to make their meat more tender, and even used as an ingredient in perfume that they believed served as an aphrodisiac. The shape of the seeds is even said to be the inspiration behind the archetypal symbol of love – the heart.

The Romans were so obsessed with the herb, that they made reference to it in many of their songs and poems. It was the subject of intense study by the man considered the father of botany, Theophrastus, and people hoarded as much of it as they could, including Julius Caesar.

It may have been the first effective form of birth control

One of silphium’s most used and praised functions was as a contraceptive. In fact, the plant might have served as the world’s first effective form of birth control. “Anecdotal and medical evidence from classical antiquity tells us that the drug of choice for contraception was silphium,” said historian and Greek pharmacologist John Riddle.

Ancient writing tells us that ancient physicians, like Soranus, would prescribe the ingestion of silphium monthly to both prevent pregnancy and to “destroy any existing [pregnancy].” This means that not only was it a contraceptive, but it also served as an abortifacient.

Ingesting the sap of the plant could induce menstruation, as well as the purging of the uterus. It not only made a woman temporarily infertile, but it could trigger miscarriages.

Farmers couldn’t figure out how to regenerate the plant

Demand for silphium in ancient Rome was through the roof. At first, Cyrene had a monopoly on the market because it only grew there, and it became such an integral part of the economy that they even put it on their currency. However, the plant’s rise in popularity ultimately caused its extinction.

Silphium seemed to have only been able to grow wild. The ancient botanist Theophrastus and farmers of the plant couldn’t figure out how to grow it intentionally, so they had to enforce strict rules on how much could be harvested. Pliny the Elder wrote of farmers who would fence off the meadows to try and prevent wildlife from eating their limited supply of silphium.

Unfortunately, there were many forces against the preservation of the herb. Shepherds rebelled and tore down the fences blocking the meadows so that their sheep could eat the plant, making their meat more valuable. Additionally, smugglers would remove the entire plant, roots and all, to try and increase their supply to sell on the black market.

It appears that farmers understood that silphium grew better from its roots than from its seeds, so they restricted how much root could be harvested. However, unwanted harvesters likely overgrazed and overharvested the plant right to its root, killing it.

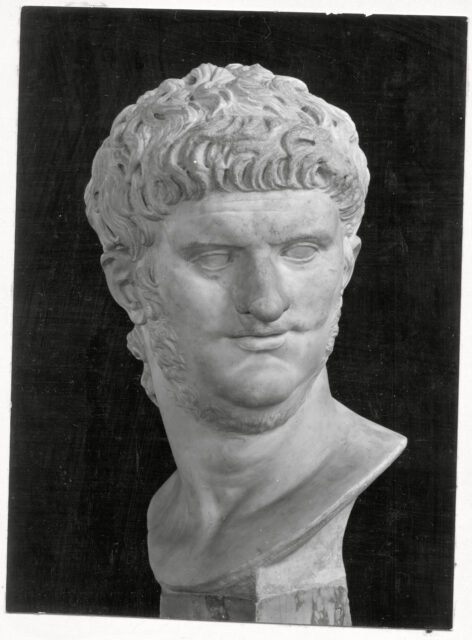

Emperor Nero had the last of the silphium

Supplies of the plant dwindled drastically. Pliny called silphium “one of the most precious gifts of Nature to man” but unfortunately, it went extinct due to its overharvesting. According to Pliny’s writings, the last stalk of silphium was harvested and gifted to one of the ancient empire’s worst rulers, Emperor Nero.

It was gifted to Nero as a curiosity, something that had become so extremely rare that only the emperor was worthy of receiving it. Unfortunately, after it came into his possession, he promptly ate it. That marked the end of the silphium plant.

Over the short course of about 100 years, the plant went from being one of the most popular in the ancient Roman economy to completely extinct.

Could the plant still exist today?

While it has long been believed that the silphium species was lost to history millennia ago, some scientists say there is a chance the plant (or derivatives of it) may still exist in the same area of Libya. Very few studies have been conducted on the flora found in the area, so it could very well still exist in some capacity. One of the biggest hurdles in finding the plant is that no one really knows what they’re looking for.

This is the ferula drudeana plant. It was a a medicinal gum-resin also used as a powerful aphrodisiac and contraceptive used in the Middle East and elsewhere. Emperor Nero swore by it and was said to have consumed the last one in the world. It has now been rediscovered in Turkey. pic.twitter.com/4glQYLRVug

— The History Of The Land Of Israel Podcast (@TheHistoryOfTh5) September 29, 2022

As per Theophrastus’ explanation, the plant has a thick root covered in black bark, is extremely tall, and has a hollow stalk similar to fennel with bright golden leaves that resemble celery.

A recent study indicates there may still be existing silphium

One researcher believes he may have rediscovered the silphium plant. In 1983, Mahmut Miski happened upon a blooming yellow plant in regions of Turkey. About 20 years later, he began to notice that it shared similar traits with the ancient plant. He identified the plant as Ferula drudeana, and learned that the only other sample of the plant had been taken back in 1909.

Professor Mahmut Miski is holding a handful of Ferula drudeana plants in bloom. Miski believes species is silphion loved by ancient Greeks and Romans and considered extinct. pic.twitter.com/GEq1Ualini

— ArchaeoHistories (@histories_arch) October 21, 2022

In his own analysis of Ferula, he discovered that they were a “chemical goldmine” containing 30 secondary metabolites. This means the species may have the same medicinal and contraceptive qualities that silphium had. “You find the same chemicals in rosemary, sweet flag, artichoke, sage, and galbanum, another Ferula plant,” Miski explained. “It’s like you combined half a dozen important medicinal plants in a single species.” Additionally, Ferula has the same rapid growth properties that silphium is said to have had, especially after heavy rainfall.

There is one characteristic that could determine Ferula is not the same silphium plant, and that is the location where it was found. Silphium was only ever found in modern-day Libya, and Miski’s discovery of Ferula near Mount Hasan in Turkey was quite a ways away.

More from us: Powdered Wigs Have a Decidedly Unglamorous Origin Story

However, Mount Hasan used to serve as a home for the ancients Greeks. Although it has not been proven yet, there is a chance silphium was transported there with them. The ancient Greeks may have accidentally stumbled on another area that could cultivate the herb, one that preserved it to this day.