We know that ancient people have done some bizarre things: made human sacrifices, used urine as mouthwash, and preserved Napoleon’s penis (yes, really). Yet it feels like we are constantly discovering new and gruesome facts about our ancestors. For example, a researcher at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History has found compelling evidence that our predecessors used to eat each other.

An eerie discovery

This discovery comes thanks to paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner, one of the Smithsonian’s researchers. She had been investigating a Kenyan fossil found by Mary Leakey in the 1970s. This particular artifact stood out to Pobiner from the Nairobi National Museum collection in 2017 while she was looking specifically for bones containing bite marks. Pobiner hoped to investigate how ancient animals used to prey on these early humans.

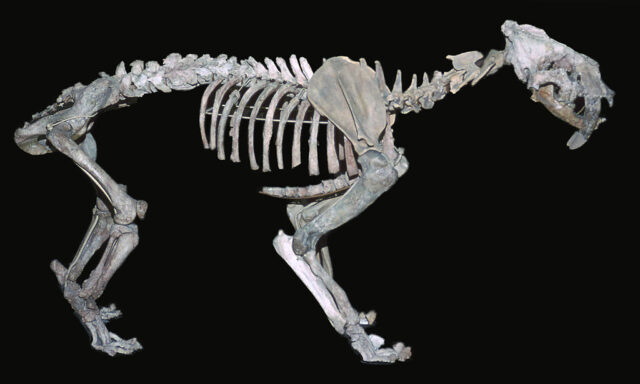

This particular artifact, a shin bone, had previously been dated to be nearly 1.5 million years old. While investigating two animal bites, which were likely from a saber-toothed cat, she also came across other marks that were certainly not. They were actually nine repetitive cuts going in the same direction. Well-versed in the field, Pobiner recalled thinking, “Wow, I definitely know what this is.” They could only have come from a stone tool used to cut the meat from the bone.

A thorough analysis

Despite her knowledge of the topic, Pobiner wanted to ensure that her theory was correct. She and other researchers published a study reporting their findings and the unique way they got answers. Pobiner decided to use the same material used by dentists to take teeth molds to make molds of the cuts she identified on the bone. These were then sent to fellow paleoanthropologist Michael Pante at Colorado State University for analysis.

To make sure that she didn’t bias his analysis, she didn’t tell him what the molds were of. After comparing the supposed cut marks to a vast database containing all sorts of other markings that could have been on the leg, Pante was able to determine that they were indeed a match for stone tools. Pobiner concluded that these were likely caused by hominids. Starving and in desperate need of food, they took it from already-dead relatives.

What we don’t know

Although the researchers gathered a lot of information from their analysis of the bone, there are still many things that they don’t know. Since they couldn’t tell what type of hominid this bone belonged to or which of our ancestors ate it, researchers can’t quite call it cannibalism – a classification that only applies when the eater and victim belong to the same species. If this was the case, this could be one of the earliest known examples of cannibalism.

More from us: Human Skulls Found in Cave Near Jerusalem Were Likely Used in Roman Necromancy Cult

Pobiner also explained that they don’t know for sure that the meat was even eaten. “We just know that some tool-wielding hominin came and cut meat off of that bone. The most plausible explanation is that they did that to eat it,” although this isn’t a certainty. The role of the saber-toothed cat that feasted on the bone is also a mystery. It may have been that the animal came across the bone after the hominins were done with it, or it might have played an earlier role.