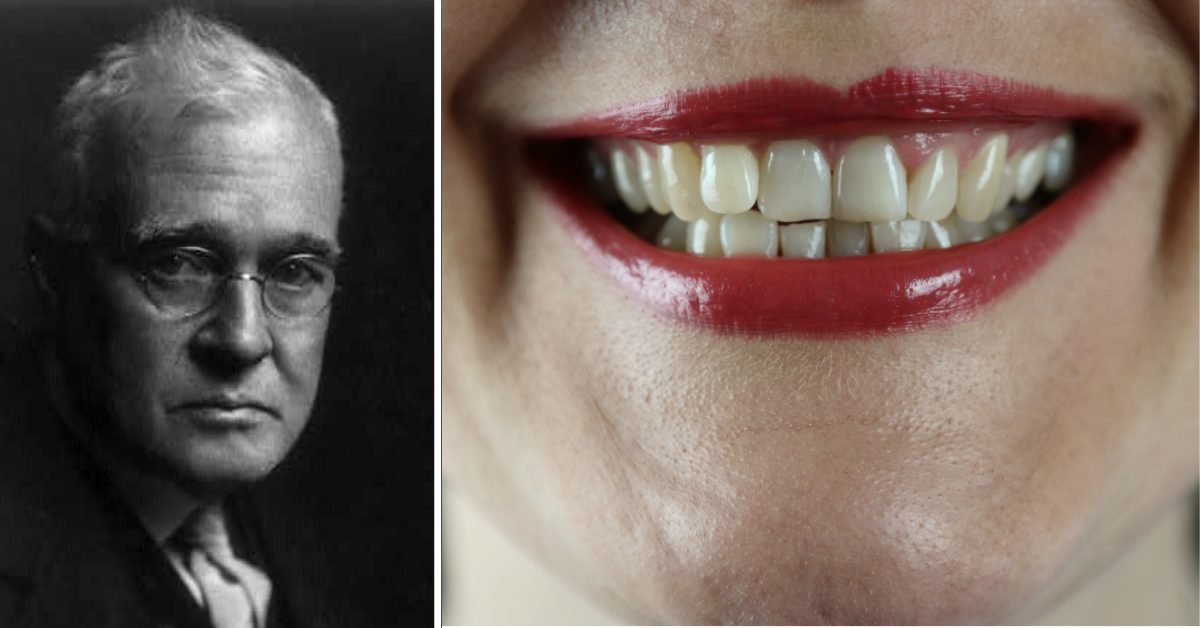

Horace Fletcher stumbled on a food craze that captured the world’s imagination in the early 20th century: extreme chewing.

Nicknamed “The Great Masticator,” Fletcher made people’s mouths the gatekeeper of health and well-being. Only by grinding a meal to liquid form between the teeth could dietary enlightenment be achieved.

But how did it catch on? Why was it so popular? And did it really work?

Horace Fletcher sank his teeth into the art of dining

Fletcher’s discovery happened during a period of isolation. Beforehand, he’d been an enthusiastic gourmet. Passions for literature, art, and other free-spirited areas led the future food faddist to treat his body as a convenience rather than a temple.

Alarm bells sounded over his health. The website Narratively writes that a rejection for life insurance hit especially hard. Fletcher was aware things had to change. Little did he suspect that a shift in eating habits would take his life down a very different path.

Inspiration struck during an extended business trip to Chicago. The lonely and middle-aged Fletcher started following the advice of parents across the land — to chew his food. Longer lasting meals certainly killed some time.

However, Fletcher didn’t just chew. He chewed and chewed till there was no solidity or flavor left to his food.

Believing he was onto something, the swallow-averse self-promoter coined a new term — Fletcherism. In a vintage article from 1928, Time magazine quotes some accompanying lyrics:

“Each morsel you eat, if you’d be wise / Don’t cause your blood pressure e’er to rise / By prizing your menu by its size.”

Things got technical, with chew tallies being recorded. Narratively mentions an average rate of 100 chomps per minute. And washing down your meal also became a process — drinks were to be swilled around the gums for approximately 30 seconds before swallowing.

“Fletcherism” was a dinner party sensation

The Great Masticator’s approach wasn’t embraced by scientists, though interest from researchers was to come. When it came to dinner party circles of the great and good, however, mastication was a foodie fixture.

His ideas traveled from the United States to Europe. Narratively highlights a piece from the Phillipsburg Herald, dated 1903. It mentions a London dining scene “threatened with too much flesh.”

Those attending so-called “munching parties” were required to assume a certain position for optimum results. Narratively describes how they “sat elbow-to-elbow in concentrated silence, their heads bowed low over their plates, allowing their tongues to rest against the roof of their mouths.”

The gatherings made a marked contrast to typical social events. Talking wasn’t exactly compatible with the occasion. Some found the accompanying sound effects a turn-off, though that didn’t stop Fletcherism from taking hold.

To make sure everything followed the correct procedure, stopwatches were reportedly used to time chewing sessions.

As attendees contorted themselves for supposed health reasons, Fletcher expanded his theories. He started making multiple menu cards featuring different food items and what it took to pulverize them. For example, a shallot reportedly needed a jaw-aching 722 chews before it could reach the gullet.

Through his efforts, Fletcher came to believe the human body was attuned to digestion. As some food matter began flowing down into the stomach involuntarily, he saw this as a sign of Mother Nature taking control.

One notable detail of Fletcherism was its inclusiveness. Unhealthy foods weren’t ruled out, as long as they were sufficiently masticated.

Mood and psychology played a role, alongside appetite and consumption. In their summary of Fletcher’s life, the National Library of Medicine writes: “People were cautioned not to eat except when they were ‘good and hungry,’ and to avoid dining when they were angry or worried.”

The Great Masticator chomped his way to success as a diet expert

Members of the public gave Fletcher the thumbs up. It took time to convince the scientific community.

Figures such as Englishman Dr. Ernest Van Someren, who wound up presenting a paper to the British Medical Association in 1901, and Yale University’s Russell H. Chittenden lent credibility to Fletcher’s newfound image as a diet guru. He also had an association with cereal magnate John Harvey Kellogg, who applied Fletcher’s ideas at the infamous Battle Creek Sanitarium.

When attention from learned individuals came, Fletcher took full advantage. He became a chew-fueled cheerleader of sorts, performing publicity stunts and establishing himself as an authority.

As to what he was an authority on, experts weren’t sure. Fletcherism cut down overall food consumption, and it’s thought this was its main strength. Fletcher ascribed a few qualities to his brainchild, saying at one point that it might even reduce crime levels!

More from us: High Fives: The Strange, Compelling History Of Slapping Skin

Overall, Fletcher made an impact on the world of dieting. But it was a dent rather than a crater. By the time of his death in 1919, society had become de-Fletcherized.

The phenomenon went from the good stuff to the brown stuff in a matter of years. Appropriate, really, given that Fletcher studied his poop as part of the process.