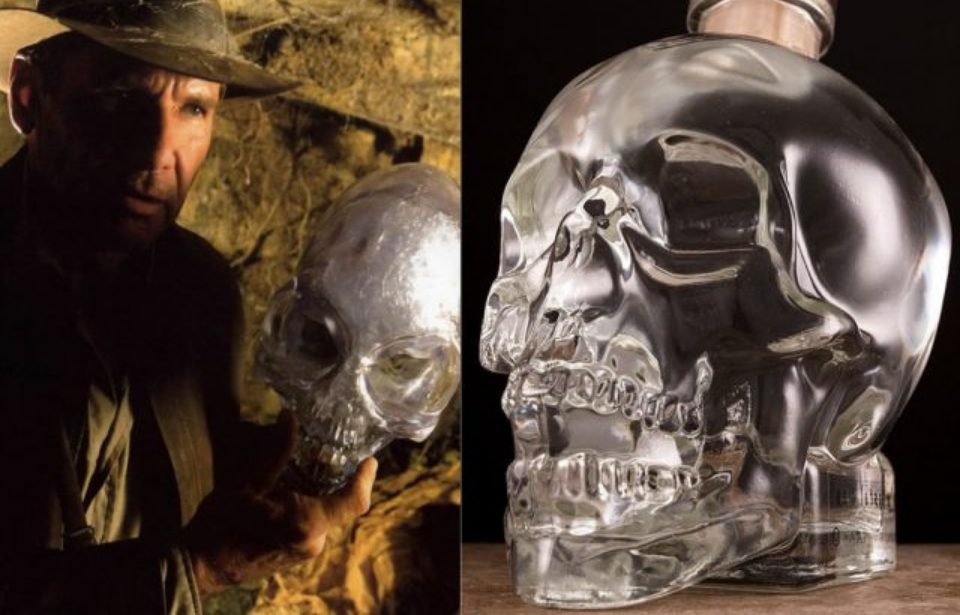

Crystal skulls have become a well-known phenomenon thanks to the Indiana Jones franchise. Although they have become so popular and their look is extremely aesthetically pleasing, facts about crystal skulls often get wrapped up in the mythology behind them. Here are some of the most famous myths on crystal skulls debunked once and for all.

Myth: Ancient or alien origins

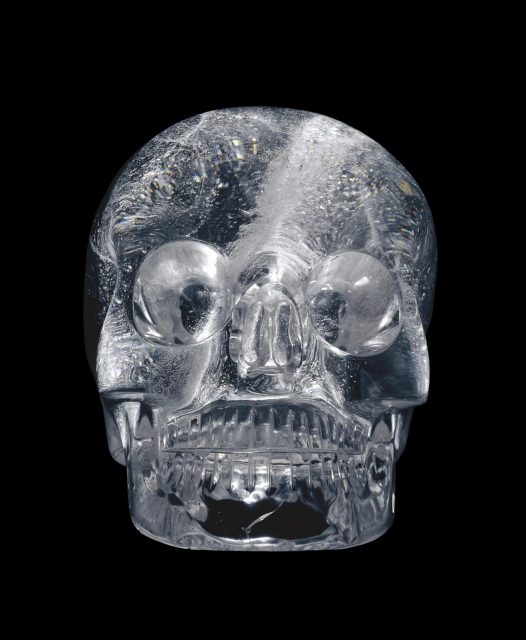

The handful of crystal skulls scattered throughout the world are part of both public and private collections. Supposedly, there are 13 of these skulls that originated in ancient Mesoamerica and were carved by either the Aztec or Mayan civilization.

Some believe that if these 13 skulls were reunited, they would disseminate universal knowledge and secrets critical to the survival of humanity. However, these 13 skulls should only be unified when humanity is prepared for these secrets.

Other popular origin stories surrounding crystal skulls include both the lost city of Atlantis and aliens. Believers speculate that these skulls were relics from Atlantis or given to the Aztecs by aliens sometime before the Spanish conquest.

Reality: 19th-century origins

Although the idea that these skulls had ancient origins is very interesting, the reality of the situation is much different than their supposed origin story.

Until the 1990s, museums housing crystal skulls seemed to corroborate the ancient origins of crystal skulls. However, in 1992, a mystery skull with no return address showed up at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. Soon after this anonymous delivery, the skulls’ origins would finally be unraveled.

This bowling-ball-sized skull fell right into the lap of Jane McLaren Walsh, an expert in Mexican archaeology. Walsh found that the skull that the Smithsonian had been given had seemingly appeared out of nowhere in the late 1800s.

Walsh then begin examining other crystal skulls in different collections and attempted to track down their history. As she worked backward, she found that she was able to trace different skulls back to a very similar time period.

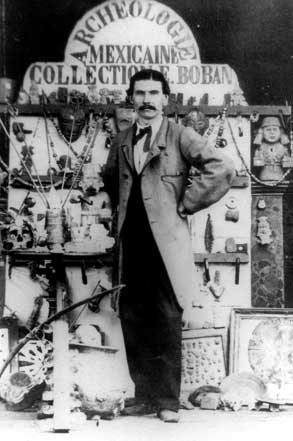

All records of the skulls she looked at had records from the 1860s to the 1890s, and all had connections to a Frenchman and amateur archaeologist named Eugene Boban. Boban, who “specialized” in Aztec artifacts, would frequently travel back and forth to Mexico where he would purchase antiquities and sell them in his shop.

Boban sold a large portion of his original Mexican archaeological collection, including three crystal skulls, to a French explorer named Alphonse Pinart. In 1878, Pinart sold this collection to the Trocadero, the precursor of the Musée de l’Homme.

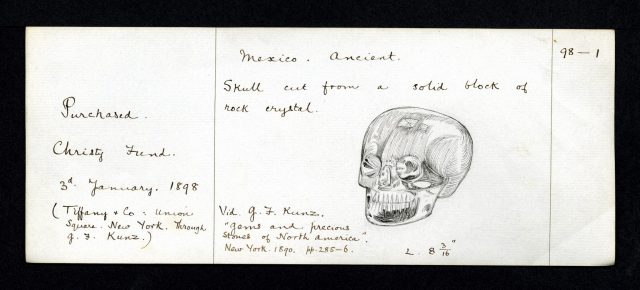

In July 1886, Boban moved his museum business and collection to New York City and auctioned off several thousand Mexican archaeological artifacts. One of these artifacts was a six-inch crystal skull that Tiffany & Co. bought for $950. This skull was sold to the British Museum a decade later.

Walsh believes that the crystal skulls that Boban sold in the late 19th century were made in Mexico around the time they were sold, between 1856 and 1880, either by one person or several in a single workshop.

Myth: Crystal Skulls have healing powers

A significant part of the myths surrounding crystal skulls is that they have healing powers. This portion of the myth also stems from the skulls’ supposed ancient origins.

Because crystals and gems have been used throughout ancient times and cultures for their mystical healing powers, believers in the crystal skulls think that ancient people deliberately carved crystals into skulls to increase their ability to impact human healing.

Supposedly, crystal skulls are equipped with natural healing properties associated with different stones, which in turn resonate at different frequencies of healing and consciousness. Joshua Shapiro, co-author of Mysteries of the Crystal Skull Revealed, claims both healing and expanded psychic abilities for people who have been in the presence of skulls.

Reality: Skepticism and Aztec gods

Most archaeologists and scientists are skeptical of the healing powers of crystal skulls. However, skulls were prominently featured in Mesoamerican religion and artwork, so perhaps that is where the mythical healing powers of crystal skulls come from.

According to Michael Smith, who is a professor of anthropology at Arizona State University, skulls were a symbol of regeneration — especially for the Aztecs. He says, “there were several Aztec gods that were represented by skulls, so they were probably invoking these gods. I don’t think they were supposed to have specific powers or anything like that.”

Although there is no irrefutable proof that skulls do not have healing powers, there is also no direct evidence correlating with individuals being cured of ailments by using crystal skulls.

Myth: The Skull of Doom

Arguably, the most famous case of a crystal skull is the case of the “skull of doom,” also known as the Mitchell-Hedges Skull. The story of this skull of doom encompasses all the mythological factors associated with crystal skulls. Allegedly, this skull was found in the mid-1920s by Anna Mitchell-Hedges, who was the adopted daughter of a British adventure and traveler F.A. Mitchell-Hedges.

Anna claimed that she found the skull beneath a sacrificial altar in a Mayan temple in Lubaantun (in modern-day Belize). F.A. Mitchell-Hedges in his book Danger, My Ally writes that the skull is a “skull of doom” that must have taken at least 150 years to rub down to pure crystal and was at least 3600 years old.

In this book, F.A. Mitchell-Hedges states that people who have mocked the skull ended up seriously ill or even dead.

Anna Mitchell-Hedges had the skull in her possession until her death in 2007. It was rarely in the public, which made it difficult for scientists and archaeologists to run any tests on it to figure out its origins.

However, Anna claimed that the skull had been used for “healings” a number of different times. The skull is now called the “Skull of Love” on its official website.

Reality: Fictionalized tales and another 19th-century skull

After extensive investigations done on the skull of doom, it is safe to say that the skull is a phony. For starters, no single crystal skull has ever been recovered from a documented excavation site. Similarly, in F.A. Mitchell-Hedges’s book Danger, My Ally, there is no mention of Anna uncovering the skull at all.

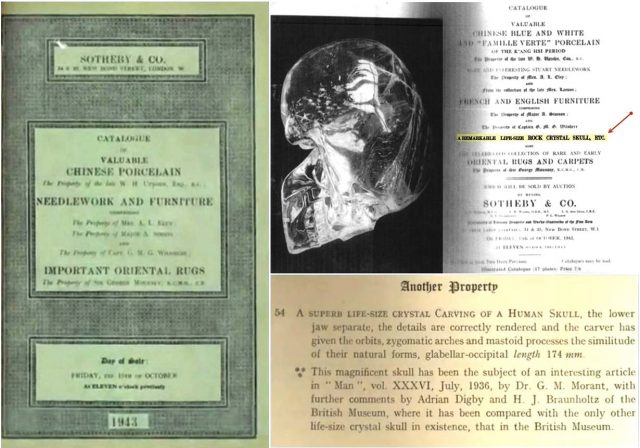

There are also issues with the dates associated with the finding of the skull of doom. F.A. Mitchell-Hedges claimed to find the skull in the 1930s, while Anna claimed to uncover the skull in the Mayan temple in the 1920s. In reality, however, this skull had been sold in October 1943 to F.A. Mitchell-Hedges at a Sotheby’s auction in London.

More from us: Did Vikings Use Crystals To Navigate The High Seas?

So, the skull was not found in an ancient Mayan temple, but it also isn’t even of ancient origin. Archaeologist Jane Walsh, who has examined and run tests on the skull concludes that the skull is not Mayan at all.

Rather, it was carved with high-speed, modern, diamond-coated lapidary tools. In other words, the skull was created sometime in the early 20th century. She guesses that the skull of doom was created to copy the Tiffany & Co. skull that is now the property of the British Museum.