A giant wave of sticky molasses sweeping through a town and carrying buildings away sounds like something you might see in a children’s cartoon.

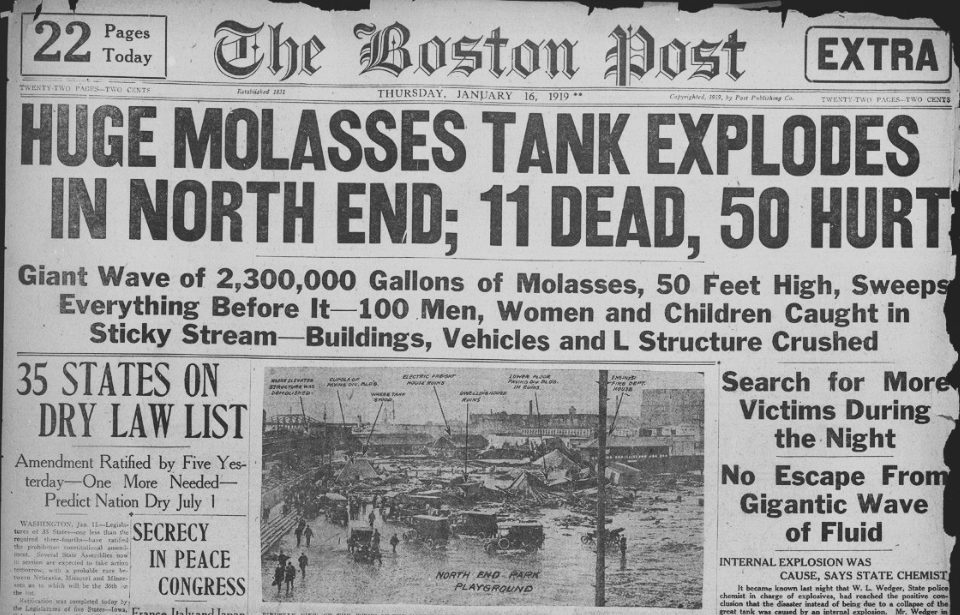

But in January 1919, exactly this happened in the city of Boston, Massachusetts, when a 50-foot tall molasses container burst, and there was nothing remotely funny about it.

Why would anyone have a giant tower of molasses anyway?

The storage tank was located at the Purity Distilling Company on Commercial Street in Boston’s North End and belonged to United States Industrial Alcohol (USIA). This sticky substance was used to make ethanol, used in manufacturing both industrial alcohol and munitions.

Molasses was stored in the 50-foot high tank next to the harbor until it could be piped to the ethanol plant.

According to History.com, the tank had been built in 1915 as part of the war effort, but construction had been “rushed and haphazard.” The container had frequent leaks, and the groans and creaks it emitted when filled became background noise to local residents.

At least one employee noticed that the tank was unsound, but USIA merely re-caulked the damage and left it at that. Along with shoddy manufacturing, this lack of maintenance was to have deadly consequences.

The day of the flood

A fresh delivery of molasses was made to Commercial Street on January 14, 1919. Molasses has to be warmed for transport to make it less viscous, leading some to think that adding new, warm molasses to older, cold molasses added extra pressure to the already pretty unstable tank, which burst around lunchtime on January 15, 1919

Two million gallons of molasses were released, and it formed a 15-foot-high and 160-foot-wide wave that traveled at 35mph. Streets for two blocks were flooded around two to three feet deep. Such was the force of the wave that buildings were crushed, and even the solid steel supports of the nearby elevated train platform were swept away.

Nicole Sharp, an aerospace engineer in Denver, examined how conditions on the day added to the deadly nature of the flood. If the flood had happened in the heat of summer, then it’s likely the molasses would have spread out further and come in a thinner layer. As it was, the mild winter day meant that the molasses moved like lava or a mudslide, and those dragged under were soon suffocated.

The Boston Post gave the following description of what it was like in the immediate aftermath: “Here and there struggled a form ”“ whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell. Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass, showed where any life was.”

A tragic death toll

Those who survived the initial surge found that they were suddenly in dire straits as the molasses began to harden around them. Horses were unable to free themselves, and many had to be shot after they began getting stuck in the molasses.

In all, 21 people were killed that day, and another 150 were injured. Police, firefighters, the Red Cross, and even sailors from the USS Nantucket that was docked nearby searched for survivors. As the winter chill set in, the molasses began to set even harder, making the rescue of victims an exhausting task.

So many were injured that doctors set up a makeshift hospital in a nearby building. When rescuers came across a dead body, the thick glaze of molasses made identification almost impossible. Some bodies had been swept into the water. The remains of Cesare Nicolo, a wagon driver, were not recovered from harbor until four months after the disaster.

The air smelled sweet for decades

Over 300 people turned up to help clean up the streets in the wake of the disaster. Brooms and saltwater pumps were used to clear some areas, while sand was employed elsewhere to absorb the molasses. Saws were needed where the molasses was set and thick, and the harbor water was discolored brown until summer.

The clean-up effort ended up being immense because rescuers, victims, clean-up crews, and those who’d come to see the site of the tragedy tracked molasses onto subway platforms, into trains and streetcars, and up and down otherwise clean streets.

Even after it appeared that every trace of molasses had been removed, residents swore that the air in the North End was tainted for many years afterward. As journalist Edwards Park put it: “The smell of molasses remained for decades a distinctive, unmistakable atmosphere of Boston.”

Legal wranglings over who was at fault

Following the tragedy, 119 different lawsuits were filed against USIA. In their defense, USIA claimed that the tank had been sabotaged. The company alleged that in 1918 an unidentified man had called USIA and threatened to blow up the storage tank with dynamite.

The cases ran for five years of legal proceedings, resulting in over 1,500 exhibits and 1,000 witnesses. The closing statements alone took 11 weeks.

Eventually, a ruling was given in April of 1925. State auditor Hugh W. Ogden declared that USIA was responsible for the flood due to poor planning and initial construction as well as a lack of oversight and maintenance in the subsequent years.

The victims were awarded a combined total of $628,000 in damages, which would be equivalent to over $9 million in 2020.

Doomed from the start

The finding that USIA was responsible for the flood seems to be supported by evidence both in the trial itself and in studies done after the event.

Over the years, several contributing factors to the tank’s collapse have been identified. As well as the idea that warm molasses on top of cold would have resulted in expansion, there’s also the theory that fermentation inside the tank would have produced carbon dioxide, which added to the growing internal pressure.

Furthermore, the winter had been particularly mild and temperatures had risen from 2°F to 41°F in the course of a day, meaning the molasses was less viscous than it would be in cooler weather.

There were also accusations that those supervising the initial construction of the tank overlooked safety tests such as filling it with water to check for leaks. Tests undertaken in 2014 by structural engineer Ronald Mayville revealed the steel used for the tank was half as thick as it should have been. It also lacked a decent amount of manganese in its composition, so the resulting metal would have been more brittle than usual.

In addition, the rivets were of a poor quality and soon began to crack under the stresses placed on them.

After construction was completed, warning signs such as creaks and groans when the tank was filled were ignored. Leaks were not repaired either competently or at all. In fact, locals would bring cups and containers to catch the leaking molasses and take it home for their own use.

What the site looks like today

The tank was never rebuilt and the site was instead taken over by the Boston Elevated Railway Company.

More from us: Ten Bizarre Historical Events That Really Happened

Today, the area is the location of Langone Park, and a small plaque attached to the neighboring Puopolo Park marks the disaster. The position of the tank’s concrete slab base has been identified as being buried about 20 inches beneath the baseball diamond at Langone Park.