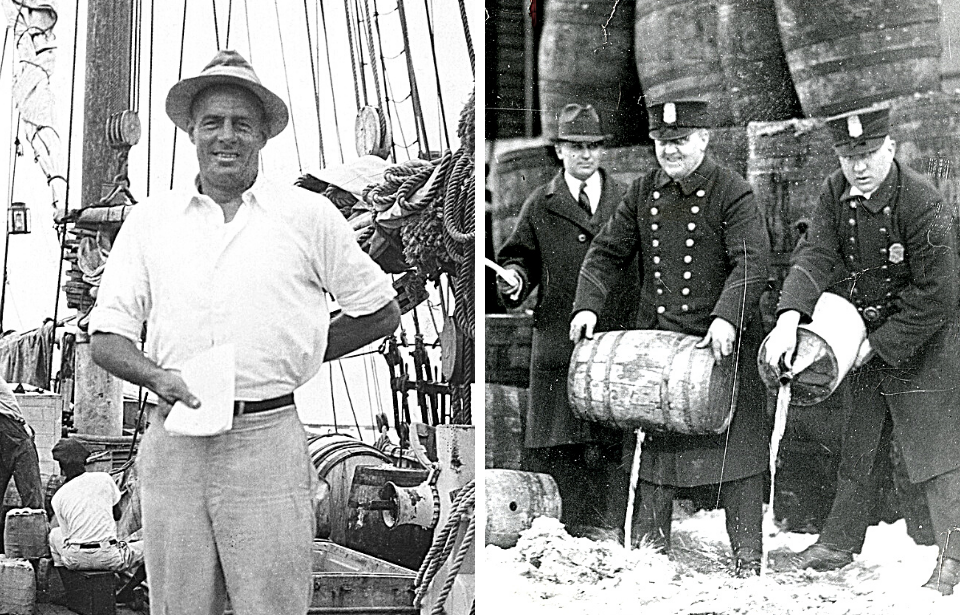

William “Bill” McCoy was a smuggler and a gentleman. He went from being an unlucky aristocrat to an overnight success. He imported illegal alcohol during prohibition, but technically didn’t break any laws and created a legacy as one of the most successful and most wanted smugglers during prohibition.

A taste for the money

McCoy and his brother were running a failing business. While at sea, a rum-runner approached them to make a drop for $100. They refused, but this planted a seed in McCoy’s mind that would turn into a very successful and semi-legal business. In 1921, McCoy invested in a 90-foot schooner and made his way to the smuggling port of Nassau in the Bahamas.

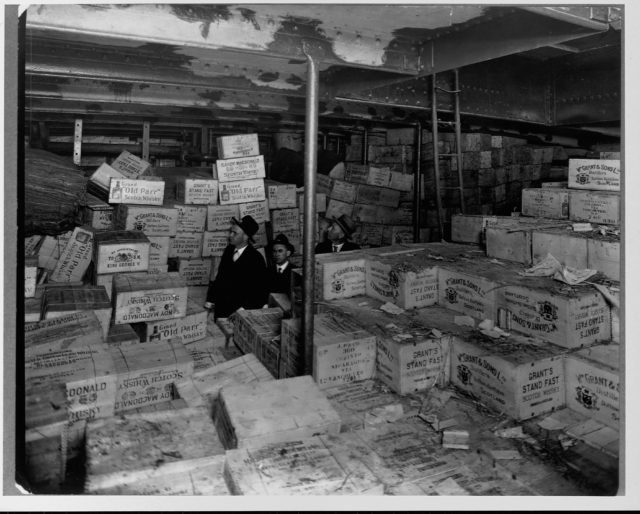

Here, he loaded up 1,500 cases of Canadian whiskey and made his way back to US waters. Once he arrived back, he sold that whiskey for $15,000 — tax-free. He was immediately hooked. It didn’t take long for him to buy a second schooner, and convert his ship into a floating liquor store that sold any kind of booze you could imagine.

He parked and operated his vessel legally just inside international waters and had rum-runners make their way through what was coined “Rum Row.” This kept his business semi-legal and put the real risk on those who brought the alcohol ashore.

‘The Real McCoy’

When you bought from McCoy, you knew you were getting a good quality product. McCoy never cheated people with his alcohol, and never tried to cut it with water or chemicals. His prices were always good, you didn’t have to worry about being robbed, and loyal customers even received a free case when they paid.

McCoy wanted to keep his business as legal as possible. He refused to smuggle other illegal products and made sure no more than two potential buyers were aboard his vessels at any one time. His desire to keep things clean earned him a glowing reputation, and his business really flourished. Because of his reputation, he became known to many as “The Real McCoy.”

Developing new techniques

Beyond the obvious credit McCoy received for pioneering the Rum Row technique, he was also credited with making the whole smuggling process much easier. Because McCoy’s business was done in water, transportation was tricky. The conventional wooden crates that housed bottles of alcohol were not very efficient in terms of transferring from one vessel to the next. So, McCoy got inventive.

He developed something called the smugglers’ “ham” or “burlock” which made moving the alcohol a lot easier. It was a pyramid stack of six bottles tightly wrapped in straw and burlap. Not only did it weigh less, but its unique triangle shape allowed the smugglers to pack their ships from toe to tip with bottles.

Additionally, the “hams” could be stuffed with salt as well, which in the case of being caught by the Coast Guard, allowed smugglers to throw the contraband overboard without worry. The weight of the salt would cause the ham to sink, destroying the evidence that they were in the smuggling business. This was only temporary though, as the salt would eventually dissolve, allowing the ham to rise back to the surface and for the smugglers to reclaim their illegal goods later.

The time of the scam

In 1922, McCoy moved his operation to the island of Saint Pierre, located off of Newfoundland in Canada, as it had a large appeal to his rum-running business. It was a French colony that offered a port that didn’t freeze over in the winter, no existing factions to compete with, and low export taxes on all products shipped. Plus, the locals were happy to cooperate with the business as the island was pretty poor before he arrived.

With operations booming, Saint Pierre quickly became a commercial merchant town. McCoy’s business recorded over 1,000 vessels coming and shopping from his floating liquor stores. Members of the town were hired as longshoremen and crew aboard the runners. By the end of 1923, over six million bottles of alcohol were recorded as having passed through Saint Pierre.

The success Saint Pierre experienced because of McCoy eventually came to an end. When the government repealed prohibition in 1933, the town plunged into an economic depression. There was no more business in Saint Pierre, but history remembers the boom the city experienced as “le temps de la fraude” or “the time of the scam.”

McCoy to retire

It wasn’t long after McCoy brought prosperity to Saint Pierre in the form of alcohol smuggling that his days as a rumrunner would come to an end. In 1923, he was caught while onboard a vessel seized by the Coast Guard. At first, he tried to outrun them, but the six-pounder guns they were firing as warning gave him reason enough to surrender.

Initially, he was to remain on bail for two years with some pretty lenient rules allowing him to come and go from his New Jersey hotel as he pleased. Eventually though, he pleaded guilty to all counts of illegal smuggling and served a mere nine months in a New Jersey Jail.

More from us: When the Government Poisoned Industrial Alcohol to Stop Prohibition Bootleggers

When he was released from jail, he had lost most of his money and was out of the game for too long. Other crime syndicates had taken over the market. He thought it best to keep his nose out of it and allow those who were conducting the business of rum-running to keep at it without his intervention. Instead, he moved back to Florida with his brother and started a real estate and boat-building business – an honest man’s work.