Ancient Mesopotamia, located throughout what is now Iraq, Kuwait, Turkey and Syria, is referred to by historians as the “cradle of civilization.” The people who inhabited Mesopotamia are credited with the creation and advancement of many fields like astronomy, agriculture, law, math, architecture, and, of course, literacy. Perhaps one of their most important and widely used creations was ancient cuneiform, a writing system that eventually extended to other early civilizations.

Developing the cuneiform script

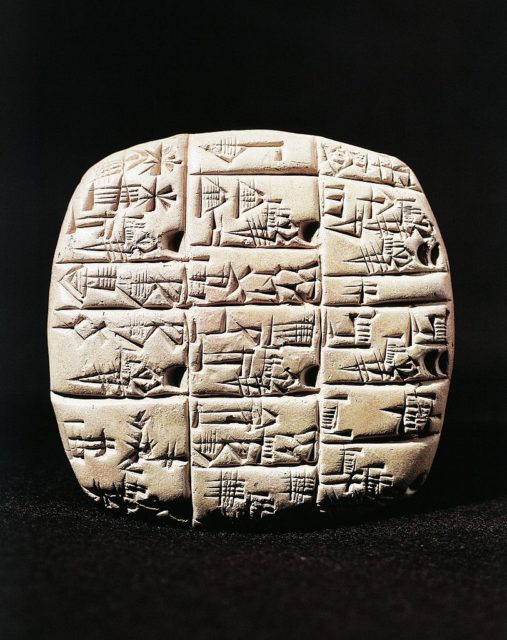

Cuneiform is the oldest form of writing in the world. It was first created by the Sumerians, the first people to migrate to Mesopotamia, as a way for city record keepers to more easily track rations (particularly that of beer and bread) and movement of supplies. It was likely officials from a temple who were tasked with this job.

Given the number of sheep, cattle, or grain to record, they needed a better way to keep track of the numbers than through memorization. When these officials created the earliest form of cuneiform, they simply drew a picture of the item they were recording and counted the quantity with either lines or circles that corresponded to how many there were.

Later, however, they used images to represent phonograms, or sounds, that could be put together similarly to how words are spelled. For example, there would be characters to represent sounds like “be” or “hu.” These signs were put together in this way so that cuneiform could be used to record spoken language.

Recording text on tablets

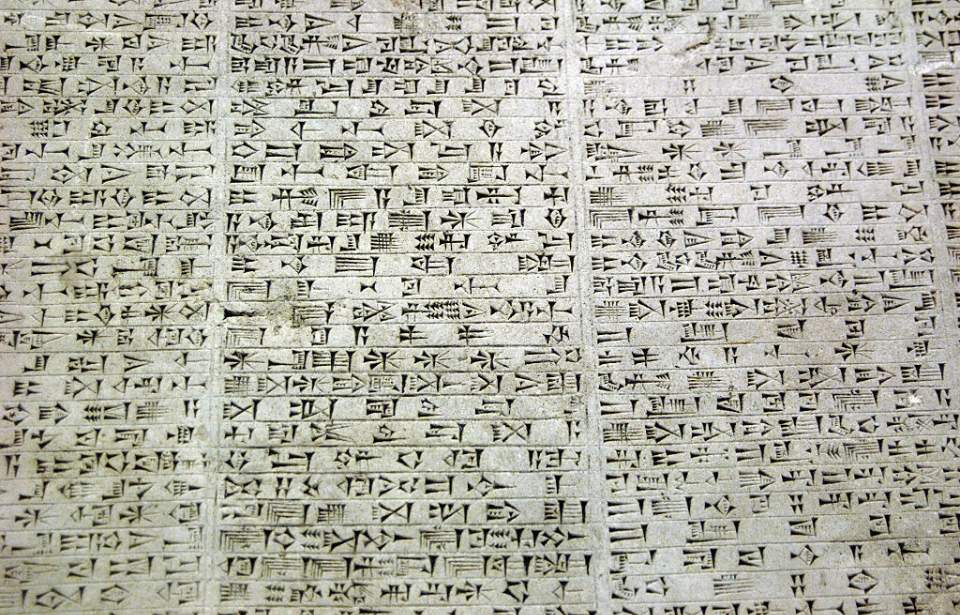

Generally, cuneiform characters were created by pressing a wedge-shaped stylus into clay that was still soft. The stylus was likely created from reeds, tall grasses that grow in wet areas. Reeds were also frequently used in ancient Egypt. It is because of the shape of this stylus that this writing style was called cuneiform, as the Latin word cuneus translates to “wedge-shaped.”

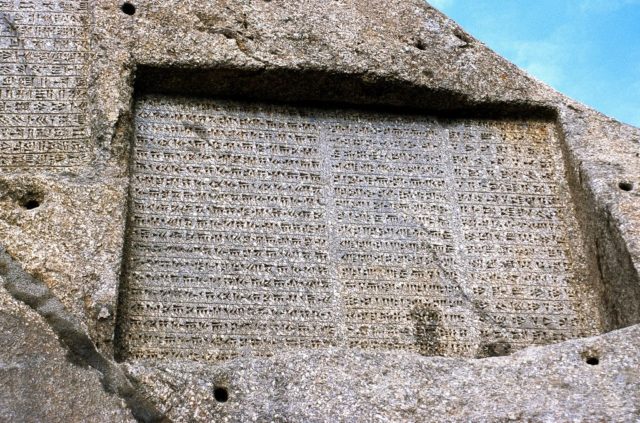

Many of the tablets that have been discovered are from the city Uruk, located in the southern part of Mesopotamia. Due to the quantity of materials coming from that location, many scholars believe that this was the site where cuneiform writing was first invented. Although tablets were one of the most common mediums for using cuneiform, the characters also appeared inscribed on rock faces and items such as beads.

Spreading the word

Much like how the Latin alphabet is used to write many languages around the world, there were many languages written in cuneiform in the Ancient Near East. Akkadian, Eblaite, Elamite, Hittite, Hurrian, Luwian, Urartian, Palaic, Aramaic, and Old Persian all used this script. Cuneiform was adapted for each of them so that it fit with their spoken language.

The earliest adaption of the script came from the Akkadian Empire, which invaded Mesopotamia in the middle of the 3rd millennium and established themselves in the region. They kept the same symbols as the Sumerians, but they pronounced them according to the Akkadian spoken language. While this generally worked, some problems were created when different characters became associated with more than one sound.

Discovering ancient cuneiform through ‘The Epic of Gilgamesh’

Although cuneiform was widely used by various different civilizations, it was eventually phased out. Instead of using a script made from characters, these civilizations changed their writing systems to adopt an alphabet. The latest known cuneiform tablet dates to 75 A.D. Attempts to decipher these tablets began in the 18th century when scholars set out to find proof that the places and events in the Bible were real.

Assyriologists, those who study the language and history of ancient Assyria, had to approach cuneiform as an entirely unknown writing system. They were successful in deciphering it, however. One of the most important translations completed was The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Sumerian story detailing the adventures of a King of Uruk. The adventure was written in cuneiform onto 12 clay tablets.

It is thought to be an inspiration for some of the stories in the Bible and is considered the earliest great literary work. The translation of The Epic of Gilgamesh allowed for many other cuneiform tablets to be translated and gave scholars a better understanding of human history because it allowed them to analyze texts that were even older than the Bible. The Bible had previously been viewed as the most authoritative book on human history, but the new understanding of cuneiform changed that.

The Library of Ashurbanipal is a vast collection of ancient cuneiform texts

Of all the collections of cuneiform tablets, the one housed at the British Museum and managed by Assyriologist Irving Finkel is one of the most extensive in the world. It holds roughly 130,000 texts or text fragments from various different areas. One of the most famous, however, is the collection of texts known as the Library of Ashurbanipal, accounting for roughly 30,000 of the cuneiform texts they have.

The Library of Ashurbanipal contained texts collected by King Ashurbanipal during his reign from 668-627 B.C. The texts were recovered in present-day Iraq in the ruins of an ancient city called Nineveh. Although the city itself was destroyed by a fire, the tablets were only made stronger as they were essentially baked and were, therefore, better preserved.

More from us: The Archaeologist Who Discovered King Tut’s Tomb May Have Stolen His Treasure After All

The Library of Ashurbanipal contained both Sumerian and Akkadian versions of cuneiform texts on a variety of different subjects including literature, medicine, religion, history, and astronomy. The first texts were found by Austen Henry Layard, a British scholar, in 1850. They were immediately taken to the British Museum where they are still kept today, along with ancient texts discovered in later years.