Scientists have made a remarkable discovery inside a cave in the remote mountains of Siberia – a 54,000 years old Neanderthal family. Research helped to identify the fossils of a father, his teenage daughter, a young male who was likely a cousin or nephew to them, and an older female who was probably an aunt or grandmother.

The fossils are from the first known Neanderthal family to be discovered, providing researchers with new insights into prehistoric family dynamics and shedding light on just how human our ancient ancestors were.

Who were the Neanderthals?

Thanks to recent scientific breakthroughs in DNA research, scientists were able to extract DNA from 17 bones and teeth found in Siberia’s Chagyrskaya Cave. The bones once belonged to seven male and six female Neanderthals, all of whom are believed to have lived at the same time. Eleven of the individuals were discovered in the Chagyrskaya Cave and two were found in the nearby Okladnikov Cave. DNA revealed that the Chagyrskaya residents had extremely low genetic diversity, a rare occurrence even among ancient humans.

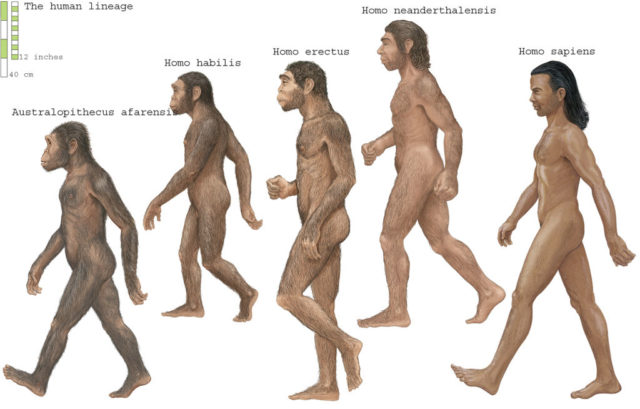

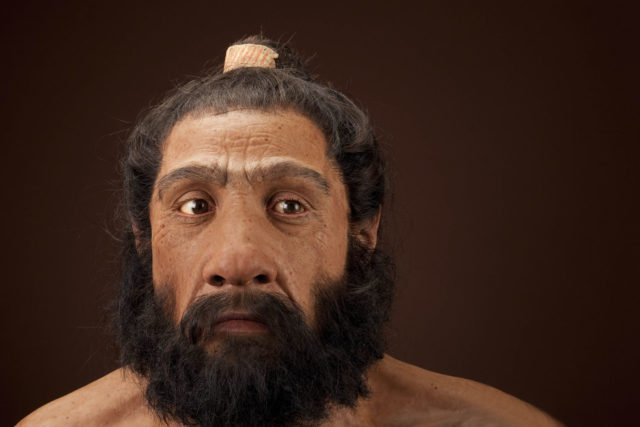

Neanderthals, or Homo neanderthalensis, are the closest extinct relatives to modern-day humans. These ancient ancestors lived throughout Europe and southwestern to central Asia between 400,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Unlike other human species before them, Neanderthals had to adapt to survive in colder temperatures where food was scarce. Even though they were far less advanced than us modern-day Homo sapiens, the Neanderthals used and crafted stone tools, controlled fire, and were adept hunters.

Colder climates meant that they more heavily relied on meat as a food source, unlike earlier human relatives who had better access to edible plants that were available year-round. Neanderthals are also the earliest known humans to create their own symbolic traditions such as burials and offerings, which is why there have been so many Neanderthal fossils discovered.

An astonishing discovery

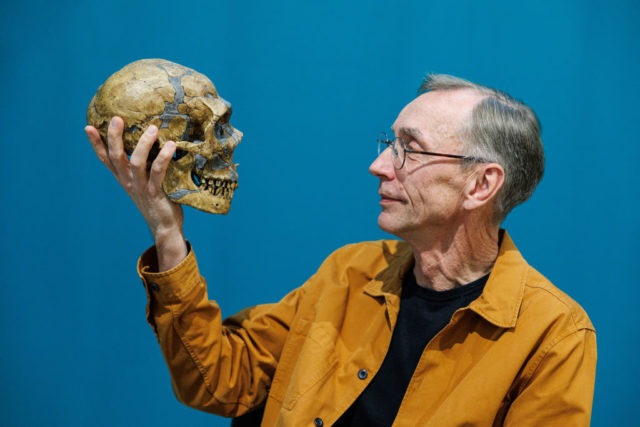

The study of the Chagyrskaya Cave was carried out by a team of researchers that included the legendary Swedish geneticist Svante Pääbo. Pääbo has made remarkable discoveries using unconventional methods like extracting DNA from the dirt of cave floors and even replicating Neanderthal brain cells. In October 2022, Pääbo was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his incredible contributions to archeology.

Findings suggest that everyone in the cave family most likely died around the same time, possibly from starvation. Pääbo was surprised they were able to identify a father and daughter using bone DNA from thousands of years ago.

The Swedish researcher has revolutionized how scientists use DNA to identify distant human relatives. In 1997, Pääbo and a team of researchers drilled into a Neanderthal skullcap found in 1856. Soon, using a sample of bone from the skull, they were able to reconstruct the entire Neanderthal genome!

Using genetics to unravel the past

The breakthrough surrounding the family connections wasn’t the only major discovery unearthed at Chagyrskaya Cave. Russian scientists have found thousands of Neanderthal bone and teeth fragments since beginning the archeological dig in 2007, along with an astonishing 90,000 stone tools from the period.

As for the family discovered in the cave, researchers like Laurtis Skov from the University of California, Berkeley, used DNA to decipher their kinship ties to one another and how they died. Researchers looked at the bones of an adult male found in the cave and compared them to a younger female. Using something called mitochondrial DNA, a set of genes passed down from the mother to her offspring, they proved that the man and woman were father and daughter, not brother and sister.

Experts also believe that the 11 people found in the cave perished all at once. “It seems to be one event that they all died in,” said Skov. These larger group deaths were not uncommon at the time. A study out of Spain reported in 2010 that a team of researchers had unearthed the remains of 12 people who died when a cave roof collapsed 49,000 years ago.

A snapshot of Neanderthal family life

The new findings from the Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov Caves have added the DNA of 13 people to the Neanderthal genome sequenced by Svante Pääbo, who had already completed 18 other individual genomes.

More from us: Ancient Cave May Have Been Hideout Used By The Last Neanderthals

Professor Lara Cassidy of the Department of Genetics at Trinity College Dublin commented on the achievement. “What makes this work particularly remarkable is that the sequenced individuals are not scattered widely across the vast expanse of Neanderthal existence, but are concentrated at a specific point in time and space, thus providing the first snapshot of a family group.”