Many people are familiar with the rhyme “in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” In school and in popular culture, we often credit Christopher Columbus as the man who discovered what is now America. We even celebrate the momentous discovery on Columbus Day each October. But the true story of America’s discovery is far less simple than a nursery rhyme.

Who discovered America?

The short answer is nobody! Before Columbus and other European explorers arrived in North America, the land was already occupied by the original inhabitants, Indigenous people. Before Columbus’ arrival in 1492, the Americas were home to more than 60 million Indigenous people. Just one century later, that number dropped to a shocking six million.

Each Indigenous nation or community had its own unique culture and governance and sustained its members with complex food systems including agriculture, raising livestock, hunting, and gathering. Some were nomadic while others built permanent settlements, often engaging in long-distance trade networks.

Was Columbus the first explorer in America?

Evidence suggests that Columbus was far from the first foreigner to arrive on North American soil. In 1960 a Viking settlement was unearthed in Newfoundland, Canada which proved that the first European to land in America was Viking leader Leif Erikson. Called L’Anse Aux Meadows, the site dates back 1,000 years ago – over 500 years before Columbus arrived – and is open to the public today as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Vikings were not the first foreigners to make a home in North America, and they definitely wouldn’t be the last. Even when the Vikings arrived, they too found Indigenous people who had called the land home for thousands of years – but did they also travel from afar to reach the “New World?”

How did humans arrive in America?

Science has proven that people likely came to North America by crossing the Bering Land Bridge, a strip of land connecting modern-day Russia and Alaska across the Bering Strait. The bridge existed 30,000 years ago during the Ice Age before it sank into the Arctic Ocean. No one knows exactly when these first settlers made the great migration over the Bering Land Bridge, but genetic studies have shown that the first humans to cross became genetically isolated from their ancestors in Asia roughly 20,000 years ago.

Archeologists believe one of the first major Indigenous groups in America was the Paleoindian-Clovis people. After arriving in North America, the Clovis people settled throughout North, Central, and South America. DNA research suggests that 80 percent of Indigenous peoples living in the Americas today are the direct descendants of the Clovis.

While science suggests one origin theory, it’s important to recognize that each Indigenous culture has its own origin story. Many groups, like the Anishinaabe, believe they have lived on their traditional lands in North America since time immemorial after the first man, Gitchi Manitou, was lowered to Earth – the name “Anishinaabe” translates to “first lowered” or “original people.”

As time progressed, early humans developed more sophisticated tools and methods for hunting, making fire, building shelter, and defending their communities. Many of these tools, like projectile points and other stone tools, have been discovered by archeologists and tell a story of how each group changed over time. The implements offer a record of their daily lives.

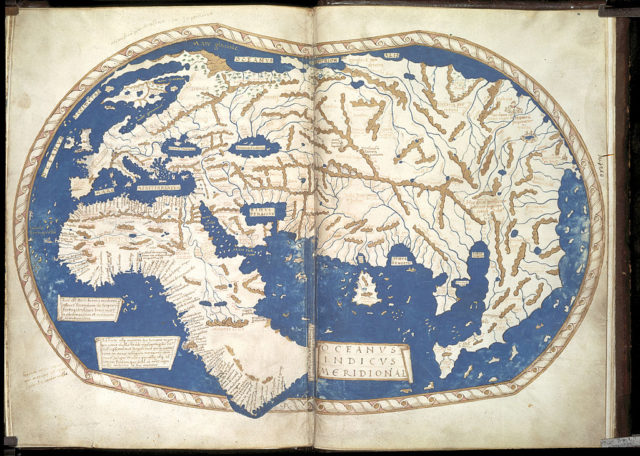

The age of discovery

Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, European nations sponsored countless expeditions in the hopes that explorers could find and claim undiscovered lands rich in resources. The Portuguese are the earliest known participants in the “Age of Discovery.” Beginning in 1420, small Portuguese ships sailed along the African coast carrying spices, gold, and even enslaved people from Africa to Europe. Other European nations, including Spain, began to take notice of Portugal’s success.

Christopher Columbus is believed to have been born in Genoa, Italy in 1451. The son of a wool merchant, he got a job on a merchant ship as a teen and remained at sea until 1476 when pirates attacked his ship. Columbus managed to float to shore on a scrap piece of wood from the shipwreck. He eventually found himself in Lisbon, Portugal, and began to study astronomy, cartography, and navigation.

As the 15th century neared its end, explorers were struggling to come up with ways to reach the far east by water. The journey by land was too long and too dangerous, as the Silk Road was lined with hostile armies and potentially lethal criminals. Portuguese explorers were able to reach the east by sailing along the West African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope.

But Columbus had a different idea: sail west across the Atlantic instead of going around the huge African continent. His idea would have worked if it wasn’t for the botched math that set the explorer up to fail. His equations were based on the wrong measurement of Earth’s circumference, making it appear that traveling through the Northwest Passage (not yet discovered) would be an easier journey than the other Portuguese routes.

Was Columbus’ mission doomed from the start?

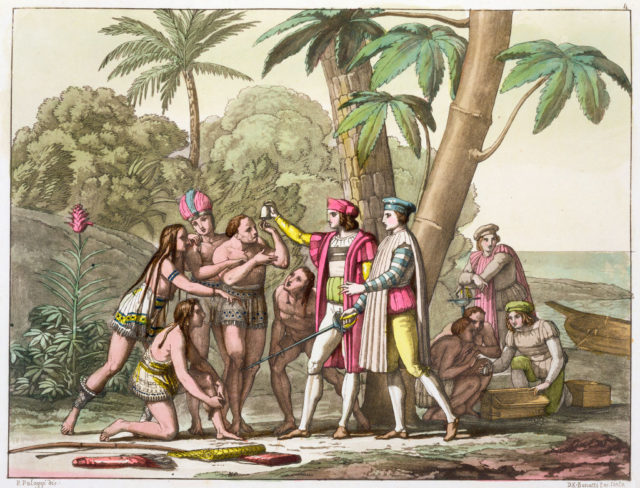

Columbus’ plans were all but ignored until 1492 when Spanish monarchs Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile took interest. The royals and the eager explorer wanted to mutually benefit from the expedition: Columbus would receive the fame and fortune he always wanted, while Ferdinand and Isabella could rake in a wealth of new goods while exporting Catholicism to the New World.

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail with a crew and three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria. By October 12, they spotted land, which Columbus believed was the East Indies but was actually the island of what’s now known as San Salvador in the Bahamas. Over the next several weeks, Columbus and his crew sailed from island to island throughout the Caribbean looking for gold, silver, pearls, spices, and any other goods of value they could bring home.

Columbus charged his crew with building a settlement in what is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Dubbed Hispaniola, the settlement was doomed from the beginning. Columbus left his two brothers in charge of building the settlement using crew members and enslaved locals.

The Indigenous Taino people were forced to search for gold and work on plantations, and within 60 years of Columbus’ landing in America, the once strong population of 250,000 Taino dwindled to just several hundred.

Columbus returns a hero

Columbus returned to Spain a hero, celebrated for making one of the greatest discoveries of his time. Throughout the early 1500s, he returned to North America several times hoping to “discover” more resources to bring home to Europe. During these expeditions, Columbus and his crew relentlessly attacked the Indigenous people living in the New World, stealing their hard-earned resources, abducting their wives, and enslaving them to bring them back to Spain as proof of Columbus’ accomplishments.

Columbus also brought more Spanish settlers with him, who quickly entrenched themselves in the New World. Apart from their physical belongings, the settlers also brought devastating diseases from Europe. When Spanish troops entered Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztec Empire, in 1520 they unknowingly introduced smallpox to the local inhabitants, and within months nearly half of the population died from the devastating disease. Scholars today believe anywhere from 50,000 to 300,000 Aztecs died.

Smallpox worked in the Spaniards’ favor. As Hernán Cortés and his troops arrived in Tenochtitlán all they found were the bodies of diseased Aztecs, which allowed the relatively small army to easily overwhelm the city.

Those who survived smallpox and measles were forced to work in fields and threatened with slavery or even death if they stepped out of line.

Who named the New World?

After his once-in-a-lifetime accomplishment in 1492, Columbus struggled to find his next amazing discovery. Sailing throughout the Caribbean – which he still believed was Asia – he was plagued by ship troubles that eventually left him stranded in Jamaica for an entire year before he was rescued in 1504.

Meanwhile, another famed cartographer realized Columbus’ discovery of the New World was actually an entirely new continent. Amerigo Vespucci put forth the idea that Columbus didn’t land in Asia but had actually stumbled upon a previously undiscovered and unknown continent. Thanks to Vespucci’s hypothesis, this new continent was named America in his honor.

By 1505, Christopher Columbus was suffering from gout or reactive arthritis, which left him bedridden for months at a time. He returned to Spain for good and remained there until his death on May 20, 1506.

Columbus’ legacy

Christopher Columbus remains one of the most renowned explorers of his time. His accidental “discovery” of the Americas is commemorated each year on Columbus Day since it was declared a national holiday by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934. In recent years, growing awareness of Columbus’ role in the systematic attacks on Indigenous people has prompted some heated debates about whether Columbus Day should be celebrated at all.

More from us: Eight of the Worst Years in the History Of Mankind

Some US states have opted to change Columbus Day to an Indigenous-focused day of celebration, like Hawai’i’s Discoverer’s Day like Hawai’i or South Dakota’s Native Americans Day, and in 2021, Joe Biden formally commemorated Indigenous Peoples’ Day with a presidential proclamation. Changing how we celebrate the holiday has helped to shift conversations around the misleading “discovery” doctrine and reflect on the ongoing effects of colonialism.