When people were caught and found guilty of crimes in 18th-century England, they could find themselves being hung from a gibbet. The gibbet was a brutal, medieval invention that was used to punish criminals even after death. Although the popularity of this punishment method was short-lived, the gibbet left behind a legacy in England that can still be seen today.

What was a gibbet?

When an individual was caught for a serious crime such as murder, robbery, piracy, or smuggling, they were typically sentenced to death. These deaths were often torturous and were used as examples of what could happen to others should they choose to take up a life of crime. Gibbeting was a way to display the dead bodies in an effort to deter others from making the same mistakes.

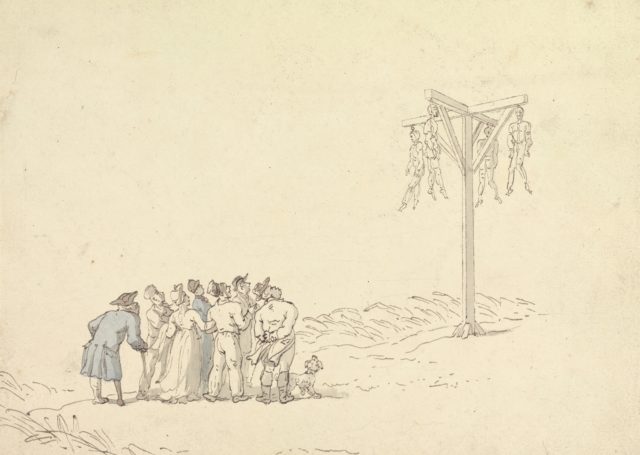

A gibbet was a structure built for the hanging of a body, either for execution or post-mortem. Typically, gibbets were tall-standing wooden posts with an arm projecting out of the upright post from which the bodies of criminals would be hung.

Gibbets were sturdy structures that were also intended to impose fear on those who saw them. Some were capable of standing for decades, with the bodies that hung from them turning into skeletons over those long periods of time. Many gibbets were over 30 feet tall and even had obstacles built into them in order to prevent loved ones from taking down the corpses that were hung from them.

The gibbet allowed for punishment after death

More often than not, gibbets were used to display the bodies of criminals that had already been executed. Their corpses would be strung up and hung as a warning to would-be criminals that they too face this gruesome fate.

In some cases, gibbeting was a form of execution. Criminals were thus hung from the gibbet and left to die from exposure, thirst, or hunger. After they eventually died, their bodies provided the same deterrent as the executions that took place prior to being gibbeted – to scare future criminals straight.

Gibbets made horrible neighbors

As one can imagine, gibbets did not make the best neighbors. As the structures were built to last, the bodies that were strung from them tended to hang for years. The corpses of criminals would slowly decay as they were left to the elements and eaten away by birds and bugs. The stench of rotting flesh would become intolerable to those living around the structures.

“You can imagine what it was like just to have a decomposing body there, especially at the beginning when there was still soft tissue,” said Sarah Tarlow, professor of archaeology at the University of Leicester. Residents living near gibbets were forced to keep their windows shut in order to prevent the horrible smell from entering their homes. This was often to no avail.

Gibbets were also rather noisy and created an eerie feeling (beyond the obvious rotting corpses that hung from them) that scared people who lived near them. The gibbet cages were often built to creak and rattle in the wind to serve as a constant reminder of the punishment for committing crimes.

The Murder Act of 1752

The practice of gibbeting was first developed in the Medieval period, but it reached its peak in the 1740s. By 1752, the Murder Act was passed in England which required that all bodies belonging to criminals must either be publicly gibbeted or dissected. Gibbeting had already declined in popularity prior to the passing of the Murder Act.

“What’s interesting about gibbeting,” Tarlow explained, “is that it didn’t happen that frequently. But it made a big splash, a big impression when it did.” When a corpse was gibbeted, thousands of people would gather to see it. The gibbeting of a living person or a corpse was a dark attraction that drew crowds to every hanging.

Women were not gibbeted

Of course, men were not the only people committing crimes in England. In fact, there were several female criminals that were sentenced to death for the crimes they committed. However, female bodies were far rarer in the medical community than male specimens and were thus a hot commodity.

All the same, female criminals were still subject to the Murder Act – their bodies had to be either publicly gibbeted or dissected. As anatomists and surgeons were desperate to study the female body, the corpses of female criminals were not gibbeted. Instead, they were given to medical professionals for public dissection.

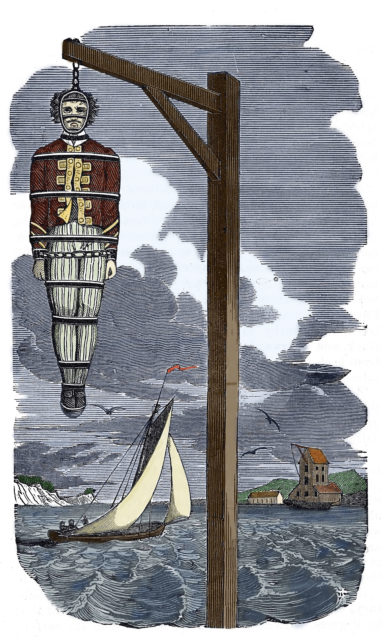

Gibbet cages came in all shapes and sizes

Gibbets were not erected every day as they were rather expensive to build, so gibbet cages were built on demand. “The chains, the gibbet cages, are person-shaped and they are designed to hold the body together and hold the body into the shape of a person—and there are other features of the gibbet that put it into this really creepy zone between living and dead,” said Tarlow.

As gibbeting was not the most common practice, blacksmiths often had little idea of what they were creating when they were commissioned to make gibbet cages. There was no standard cage that they could base their work on. As such, nearly every gibbet cage differed in size and shape, built for the individual that it was going to “house.”

All that remains of gibbets

The practice of gibbeting was increasingly seen as a barbaric form of torture for both the living and the dead. It was officially abolished in 1834 when the Anatomy Act was introduced. Over time, standing gibbets were eventually taken down, though souvenirs were often taken from the gibbets before they were removed.

More from us: The Terrifying True Story Behind Netflix’s ‘The Watcher’

However, not all gibbets were destroyed. In England, 16 gibbet cages still remain in small museums. In most cases, the former locations of gibbets are named for the criminals that hung from them. Many roads and regions in England are named after the criminals, taking the place of the physical structures.