Researchers in Israel have made an incredible discovery etched in the body of an ancient lice comb recovered from an archaeological site in 2017. Although the comb itself was intriguing when it was found, new research has revealed what they believe to be the oldest written sentence in the first alphabetic script, Canaanite. Not only is this finding important to our understanding of the language, but what it says is surprising.

Ancient Canaanite

Canaanite, also known as Proto-Sinaitic script, is considered to be the earliest form of alphabetic writing. It was first discovered by Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie and his wife Hilda while excavating a turquoise mine in 1904–1905. The pair found numerous inscriptions in the temple on site. They thought they had simply found hieroglyphs but soon realized it was something different. It’s believed that Canaanite was derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs and used between the 19th and 15th centuries BCE.

Invented around 3,800 years ago, the script moved away from using symbols as indicators of sounds or full words. Instead, each symbol represented a single letter. The script was used in many different areas and is believed to have been created in Egypt.

Making the discovery

There were also a few items with the script found in Canaan. The ivory comb was discovered at the archeological site of Tel Lachish, a large Canaanite and Israelite city. Despite being a populated area, there is very little known about the Canaanites because very few of their written records have survived.

Instead, what historians know about them comes from the texts of other people. This lice comb gives us more information about the lives of Canaan’s elite.

As ivory was an expensive material, the comb would likely have only been used by one of the wealthy residents of Lachish. While the researchers attempted to discern the age of the comb using carbon dating, a common procedure for aging ancient artifacts, they were unsuccessful. Although less precise, they are still able to date the comb to around 1,700 BCE. So how is it that researchers know the artifact was meant to remove lice?

It took them putting it under a microscope to find out.

Lice begone

When they did so, they discovered the remains of headlice stuck in the teeth of the comb, confirming their hypothesis about its purpose. The device’s design also makes it clear that it was made to rid the user of lice. One side of the comb has thick, wide teeth which would be used to comb hair. The other side contains many smaller teeth which would be the right size to remove the lice and any eggs that they laid.

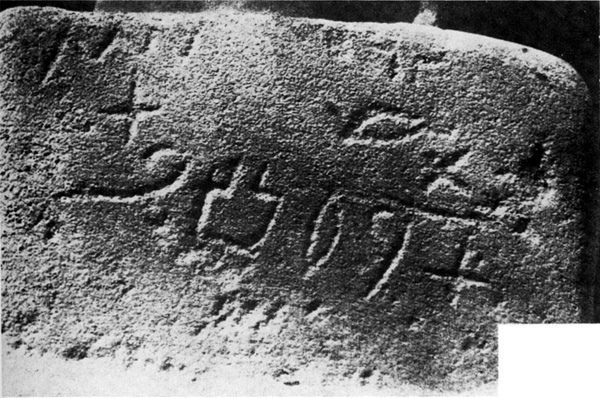

It also helps that the Canaanite inscription on the artifact says exactly what it was for. The comb reads: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.” “People kind of laugh when you tell them what the inscription actually says,” said Michael Hasel, an archaeologist at Southern Adventist University in Tennessee who was involved in the comb’s discovery.

More from us: Discovery of Unknown Fossil in Museum is Changing the History Books

Apart from being an incredible linguistic discovery, this sentence also acts as a reminder that ancient people were really no different than us. They just wanted their lice to be gone.