Modern-day Americans have a lot to be thankful for, especially when it comes to food. When the first settlers arrived from Europe 400 years ago, they didn’t have grocery stores stocked with anything and everything to make an amazing meal. Instead, they found themselves in a harsh and unknown environment where simply surviving was a struggle.

Trial, error, and necessity quickly spawned a community of resourceful people who knew the true meaning of “waste not, want not.” Survival aside, we’re especially grateful that these colonial foods are no longer on our dinner tables!

Hardtack

Not only has this recipe stood the test of time, but the actual food can also survive centuries without spoiling! Hardtack is an inexpensive and long-lasting biscuit made from flour, water, and – if you’re feeling fancy – some salt. This was one of the go-to foods for long voyages or wartime as it doesn’t spoil, making it one of the first available “non-perishable” foods before canned and prepackaged goods were commonplace.

Hardtack was typically used in military rations along with salt pork from the 16th to 20th centuries. It dates back to ancient Egypt, and some hardtack pieces dating back to the mid-1800s are on display in museums today in near-perfect condition. While this food was convenient, cheap, and portable it was also bland, hard to eat, and had next to no nutritional value.

Beaver

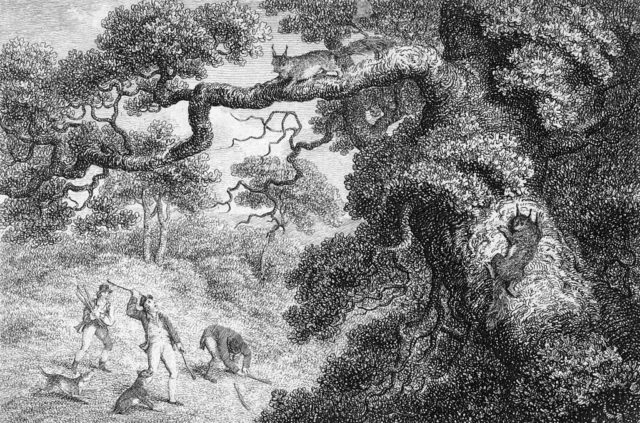

Beavers have long been a source of food and other resources for the Indigenous cultures of North America. Nations including the Cree, Mi’kmaq, Gwich’in, and Malecite all hunted beaver in the winter and spring for meat and beaver pelts. When colonists arrived in North America, they were greeted with a variety of new species they had never seen, let alone eaten.

Soon the beaver became a staple in the colonial diet, especially the tails, which had a fatty texture and gamey flavor when roasted. Beaver pelts, which are waterproof, became incredibly valuable when the fur trade arrived in the late 17th century.

Ambergris

The strange fossil-like specimen known as “ambergris” is actually whale vomit! The musky-smelling substance is a naturally occurring phenomenon made by sperm whales. The whales eat a diet mostly consisting of cephalopods like cuttlefish and squid, which contain beaks and bone-like parts that are vomited out before digestion. These byproducts become fossilized over hundreds of years before being discovered by humans.

Thanks to the rapid growth of the whaling industry in New England in the 18th century, ambergris became widely available to colonists but extremely expensive. It was often added to chocolate to give it a musky odor, and is even still used today in perfumes!

Eel pie, anyone?

What’s more American than apple pie? Apparently, it’s eel pie! Eels were a popular protein source for families in the colonies, in part because they were extremely plentiful and easy to catch. The Indigenous people in the area introduced the settlers to eels. They’d gather in large numbers and huddle together in the mud to avoid the cold during wintertime – making them a cinch to catch.

Colonists also set traps to catch eels to bring home and bake into savory eel pies. It is believed that eel was likely served at the first Thanksgiving, and is still enjoyed today in Japan and other countries around the world.

Clabber

Nearly every culture around the world has its own version of yogurt or fermented dairy product. For 18th-century settlers, it was clabber. If you’ve ever left milk in the fridge too long and ended up with a partly solid, foul-smelling goop then you know what clabber is.

Scottish and Irish settlers brought this recipe to the new world, typically made from curdled and sour milk eaten with spices like cinnamon, nutmeg, and pepper.

Tripe

Tripe was another popular food for early settlers and is still enjoyed throughout the world. Tripe is the stomach lining of ruminant animals like cows, sheep, and deer. The chewy texture and mild liver-like flavor of tripe make it a good addition to warming stews.

While the idea of eating a stomach may sound unappetizing, the colonists were all about the “waste not, want not” lifestyle – it’s no wonder they made such efficient use of their food.

Mutton

Lamb is still considered to be an indulgent and rich centerpiece to a lavish meal, but mutton on the other hand was typically regarded as a lower-class protein even though the only difference between the two is age. Lambs are baby sheep butchered in their first year of life, while mutton is made from the meat of adult sheep.

Slaughtering immature animals, especially in the early colonial period, was not only wasteful but also irresponsible. Sheep could provide milk and wool, so the longer the animal lived before slaughter meant less waste overall – thus mutton was a popular meat in the colonies and back home in Europe, even if it was tougher and less flavorful than lamb.

Ash Cakes

Similar to hardtack, ash cakes were another way to keep food fresh for longer periods and make it as convenient as possible – especially for 18th-century soldiers. Most men were issued their rations several days ahead of time while on the march, which meant their flour ration could go bad before they even have a chance to use it.

Soldiers also lacked proper tools to bake bread, so ash cakes were the easiest way to use their rations in time. Simply mixing flour and water and placing the dough over the hot ashes of a fire, an ash cake could be cooked up anytime, anywhere.

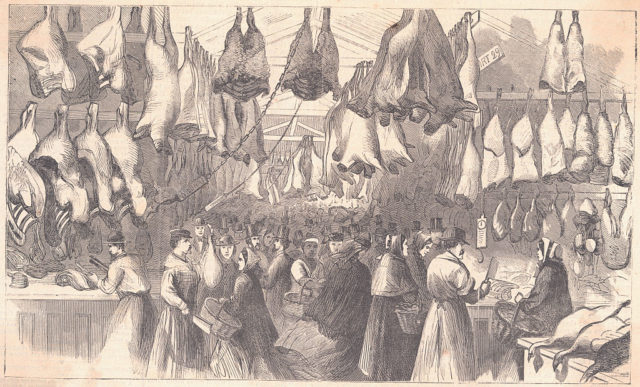

A host of roasted critters

When it comes to variety, colonists were limited to what they could find. Whether it be a particularly brutal winter, unfortunate circumstances, or a ripe opportunity, unlikely critters were often on the menu.

Settlers reportedly roasted squirrels, opossums, raccoons, swans, and even pigeons which all be readily found, as opposed to the cows, chickens, and pigs that had to be brought over from the motherland. Of course, wild turkeys and ducks were also plentiful in the colonies.

Now for dessert – let’s start with syllabub

Didn’t find anything from the main course appetizing enough? How about these colonial desserts?

Syllabub was a popular dessert made by curdling cream or milk with an acid like wine or cider and whipping it. The wealthiest families would make their dessert with imported sweet wines like sherry and serve it in special syllabub glasses. The cream creates a tart, tangy mousse-like confection that was popular from the 16th to 19th century.

Asparagus ice cream

Ice cream is a sweet treat we all know and love, but when it first became popular in colonial America it was far from the Ben and Jerry’s flavors you find at the grocery store.

In the mid-18th century, chefs began creating ice cream flavored with parmesan, asparagus, chestnuts, or – like first lady Dolly Madison – adding a handful of oysters to mix into an after-dinner treat.

Pepper cake

Martha Washington, the colonial Martha Stewart herself, made the Pepper Cake famous in the mid-18th century. Pepper was expensive and hard to get at the time, so the spiced cake was a special centerpiece for any party to showcase your wealth and status.

More from us: Merrymount: America’s ‘Gay Colony’ That’s Left Out Of History Books

According to Martha’s recipe in her cookbook A Booke of Cookery, the cake contained pepper, molasses, and candied fruit and was aged for “a Quarter or Halfe a Year.”