The first “bog body” was found in 1640, and ever since, hundreds have been turning up in peat throughout northern Europe. These mummified remains have been dated throughout several millennia, with the oldest dating as far back as 8000 BC. Categorizing them into a database has helped researchers to find trends between the different mummies, and has revealed that for many of these bog bodies, their death came through violent means.

An in-depth study of bog bodies

Dr. Roy van Beek, an archaeologist at Wageningen University & Research, along with a team of professionals, created a comprehensive database that analyzes more than 1,000 preserved bodies that were found in 266 historical bog sites across northern Europe. “While a number of bog scholars have been arguing that we need to reconceptualize bog bodies to include the skeletonized remains from more alkaline bog lands and wetlands, this is the first major study to do it systematically,” said Melanie Giles, a British archaeologist not involved in the study.

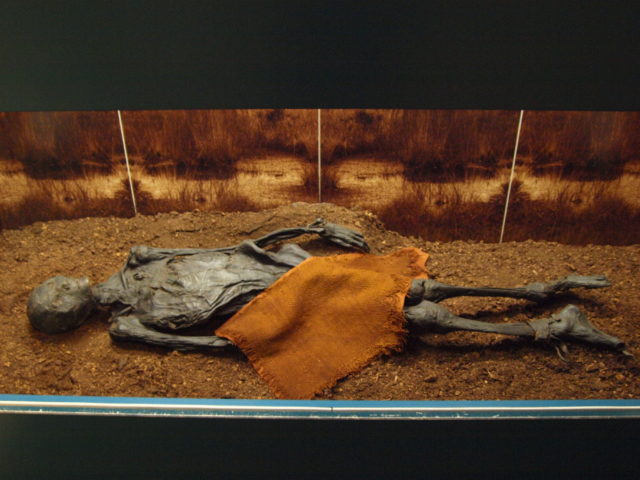

The database categorized the bog bodies into three groups: bog mummies, whose skin, soft tissue, and hair are largely preserved; bog skeletons, where only the bones of the victim are left; and a third group which is made of cases comprising both former categories.

From this database, trends in causes of death have been determined. Using data from their ages and time of death, it’s clear that a rise in bog burials occurred during the Neolithic period, carrying into the Bronze Age. Most of the cases were victims of traumatic injuries, and many were murder victims.

The bogs provided the perfect environment for mummification

These bog mummies have largely been found in raised bogs throughout northern Europe. Raised bogs are dome-shaped masses that allow peat moss to grow and thrive, typically in lowland areas. Reaching depths of 30 feet or more, these are highly acidic areas that are poor in mineral salts. These conditions make the perfect environment for the natural mummification of human bodies or other organisms.

These bodies have been covered in layers of sphagnum moss and peat which helped to preserve them for centuries. The moss and peat cover the tissue, making a cold environment that’s highly acidic and prevents exposure to oxygen. The moss also releases multiple chemicals that make it difficult for microorganisms to feed off the bodies, which would otherwise cause decay and rot. However, the sphagnum moss eats away at the bones. This disintegrates them but leaves the soft tissue behind.

The Yde Girl

The Yde Girl is a bog body found in 1897 near the village of Yde in the Netherlands. Following analysis, it was determined that she was about 16 years old when she died, which happened at some point between 170 BC and 230 BC. It was also determined that she had suffered from severe scoliosis and likely had an irregular gait.

The marks preserved on her body serve as an example of the violent ends that the bog bodies often met. Hidden underneath the woolen cloak that she was wearing was a stab wound located near her collarbone. Additionally, there was a seven-foot strip of cloth wrapped around her neck three times. “The cloth was probably used to strangle her,” said Dr. van Beek.

Other bog bodies suggest violent ends

The Yde Girl is one of many bog bodies bearing visible signs of trauma and mutilation. Other famous bog bodies found throughout northern Europe include the Windeby Girl, Clonycavan Man, Haraldskjaer Woman, Lindow Man, and Old Croghan Man. As they were all found in different states of preservation, not all bog mummies have been proven to have had violent deaths. For those that remain relatively well preserved, however, the cause of death is easily determined.

The Grauballe Man was found in 1952 in Nebel Mose bog. His remains are dated to be as early as the third century BC, during the early Iron Age period. Believed to be in his mid-30s at the time of his death, it was discovered that his throat was slit from ear to ear. His body had been preserved extremely well which made the cause of his death easy to determine.

The Tollund Man was found in 1950 in Bjældskovdal bog and is dated back to 405-380 BC. He was between 30 and 40 years old at the time of his death, which was determined to have been caused by suffocation resulting from hanging.

Within Dr. van Beek’s study, the cause of death could be determined for 57 bog mummies, with 45 of them meeting violent ends. Whether from bludgeoning, dismemberment, or mutilation, these victims did not die of natural causes. Some of the bog bodies even suggest several attacks, with their killers participating in a practice known by scholars as overkilling – the infliction of excessive trauma.

Why did they die?

A major question surrounding the discoveries of bog bodies is why they died in the first place. For some, their cause of death is quite clear. For instance, a bog was found that housed more than 380 remains of ancient warriors. The remains were determined to be all male and mainly adult in age, dating back to the first century AD. Researchers believe that those who died in conflict were swept off the battlefield and dumped into the bog, ultimately becoming mummified.

Other sites housed the remains of only one bog mummy. As these single bodies were analyzed, conclusions have been made as to their cause of death. Some believe that many bog bodies were killed as ritual sacrifices. This may have been in response to times of crisis, including famine and extreme weather. Dr. Miranda Aldhouse-Green, emeritus professor of archaeology at Cardiff University, explained that these ritual killings also served as a glue in communities. “Ceremony was key to keeping communities bound together, and ritual killing would provide spectacle similar to Roman gladiatorial shows,” she said.

As for the bodies dating back to the Iron Age, most share two common features: they were young, and they had some form of disability. Take the Yde Girl, for example. She suffered from severe scoliosis, which stunted her growth but may have also caused her to be seen as “touched” by divinity. “In some traditional societies, such individuals were perceived to have shamanic powers, enabling them to segue between the material and spirit worlds, just as people at puberty contain elements of childhood and adulthood,” Aldhouse-Green explained.

More from us: Decapitated Crocodiles Discovered in Undisturbed Ancient Tomb Were Mummified in an Unusual Way

Today, the preservation of bog lands is viewed by many as an effective way to combat climate change. “Many bogs across Europe are currently protected nature reserves, often with attempts to restore and expand them,” said Dr. van Beek.