In September 1982, Chicago was the epicenter of one of the deadliest unsolved mysteries of the decade. Over several days, seven individuals perished after ingesting Tylenol capsules laced with potassium cyanide, resulting in one of the largest pharmaceutical recalls in history and a nationwide panic.

Over 40 years on, authorities still haven’t determined the mastermind behind the Chicago Tylenol Murders, leading us all to wonder if the case will ever be solved.

What does potassium cyanide do to the body when ingested?

Before we can get into the nitty-gritty of the Chicago Tylenol Murders, we first need to explain what happens when someone ingests potassium cyanide – because it isn’t pretty. The compound looks like any indistinct white powder and has an odor described by many as resembling bitter almonds.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC): “Exposure to potassium cyanide can be rapidly fatal. It has whole-body (systemic) effects, particularly affecting those organ systems most sensitive to low oxygen levels: the central nervous system (brain), the cardiovascular system (heart and blood vessels), and the pulmonary system (lungs).”

Potassium cyanide is so fatal that death can occur just hours after ingestion. Early symptoms are typically nausea and vomiting, lightheadedness, the inability to catch one’s breath, and restlessness. As the substance makes its way through the body, the lungs fill with liquid, leading to increased breathing difficulties, and the patient may experience muscle spasms, coma and/or seizures.

The symptoms end when the body shuts down, resulting in death – and not a kind one, at that.

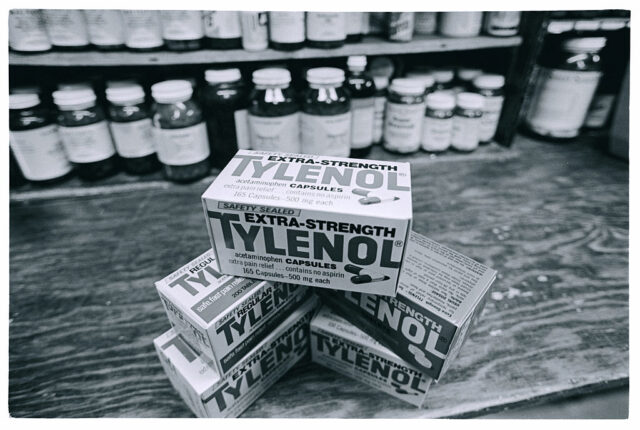

Seven deaths are attributed to extra-strength Tylenol capsules

Sources differ as to the day 12-year-old Mary Kellerman, the first victim of the Chicago Tylenol Murders, died. Some state her death occurred on September 28, 1982, while others claim it occurred the following day. What we do know is that the seventh grader was complaining of a sore throat and runny nose when her mother gave her some extra-strength Tylenol. Within hours, Kellerman was dead.

The next three victims were, sadly, all members of the same family. On September 29, Adam Janus died of a suspected heart attack, which was later determined to be cyanide poisoning. In their grief, Theresa and Stanley Janus each took extra-strength Tylenol capsules from a bottle in Adam’s home. Stanley died that day, while Theresa passed two days later.

Three other victims were later reported: 27-year-old Mary Reiner, 31-year-old Mary McFarland, and 35-year-old Paula Prince. They had no relation to each other, nor to the other victims.

A public health official sounds the alarm

Helen Jensen, a nurse and the only public health official in the Chicago suburb of Arlington Heights, was asked to investigate the three Janus deaths. When she looked around Adam’s home, she discovered a bottle of extra-strength Tylenol with six capsules missing and a receipt indicating the medication had been purchased the day prior.

Believing there could be a connection between the missing capsules and the trio’s deaths, Jensen gave the bottle to Detective Nick Pishos. The investigator contacted Edmund Donoghue, a doctor and the deputy chief medical examiner of Illinois’ Cook County, who immediately suspected potassium cyanide might be to blame.

Donoghue asked Pishos to smell the bottle, with the latter stating the inside of the container smelled like bitter almonds. This led him to contact Michael Schaffer, the county’s chief toxicologist, who tested the remaining capsules and found they were, indeed, laced with the deadly compound. In fact, they contained three times the fatal amount.

Investigators warn the public to avoid ingesting Tylenol

Upon learning about the potassium cyanide-laced Tylenol capsules, authorities held a press conference, urging the public to not take the medicine – in fact, they were told to throw out any and all bottles they had in their possession.

Tylenol’s manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, also addressed the murders, issuing warnings to hospitals, pharmacies, and other distributors. The company also halted all promotion of the product, instead releasing advertisements that urged users to stop taking any capsules that contained acetaminophen, and offered to exchange the affected bottles for solid tablets.

Investigating the Chicago Tylenol Murders

Early on in the investigation into the Chicago Tylenol Murders, detectives noticed that the bottle purchased by Mary Kellerman’s mother had been inventoried by the Jewel Foods location from which it came. They determined the lot – MC2880 – immediately prompting Johnson & Johnson to recall all batches with that number.

A search of all Chicago-area stores known to carry extra-strength Tylenol found several more bottles with capsules laced with potassium cyanide, leading Johnson & Johnson to expand the recall into what became one of the largest the United States had ever seen.

It was during this search that investigators learned that one bottle had been purchased and none of its capsules ingested, as a strange odor had been noted. Unbeknownst to the purchaser, this likely saved their life.

The tainted capsules were found to have been manufactured in Pennsylvania and Texas, leading many to theorize they’d been tampered with after being placed on store shelves. It was likely someone had purchased the bottles, swapped out the medicine within the capsules with potassium cyanide, and placed them back in the medicine aisles from which they came.

Over the decades since the murders, the investigation has been reignited numerous times, with no one found responsible. The latest update came in 2023, with Chicago-area authorities teaming up with Othram, which uses forensic genealogy to solve cold cases. Having seen success in the past, the company hopes to use its technology to extract DNA from evidence in the case.

Should Halloween be canceled?

Given the Chicago Tylenol Murders occurred close to Halloween, panic shifted from contaminated medicine to the possibility that someone could lace children’s candy with potassium cyanide. In previous years, fears had abounded over the possibility of trick-or-treaters coming across razor blades or other dangerous items while sorting through their hauls – now, the possibility of something much more deadly was worrying parents.

While many smaller towns outside of the Chicago area canceled Halloween altogether, those in and around the city opted to change what was handed out on the night of October 31. Chicago’s mayor spearheaded the circulation of one million leaflets, urging households to hand out money or small toys, while the homeowners association in the Poplar Hills subdivision told members to hand out coupons, which could be redeemed for candy at local shops.

There were three suspects in the Chicago Tylenol Murders

Despite no one having been convicted in the Chicago Tylenol Murders, three suspects were investigated. The first was James William Lewis, a New York City resident who’d mailed a letter to Johnson & Johnson, demanding $1 million to stop the deaths. When arrested by police, Lewis explained how the culprit was committing their crimes, but denied any involvement.

An investigation of the man’s home found he’d previously owned a book about poisons, with his fingerprints discovered on pages covering potassium cyanide. Without any evidence to directly connect him to the seven deaths, he was charged with extortion, to which he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Decades later, in 2007, investigators found there were discrepancies in Lewis’ story and the evidence. When confronted with this, he recanted his initial timeline, leading to a second search of his home. Official documents from the time state the Department of Justice believe him to be behind the murders – there just wasn’t enough evidence to prove so. DNA taken from him and his wife also didn’t match that on file.

A second suspect was Roger Arnold, a dock worker who told investigators that he was in possession of potassium cyanide. The owner of a bar that Arnold frequented, Marty Sinclair, told police that the man had been acting erratically and discussed killing people with a white powder. He also worked with Mary Reiner’s father and owned a copy of The Poor Man’s James Bond, which contained instructions on how to produce the deadly compound.

While spoken to several times, Arnold was never arrested in relation to the Chicago Tylenol Murders. He was, however, booked on charges of second-degree murder after killing a man he accidentally believed to be Sinclair. He was convicted of the charges against him and served 15 years of his 30-year sentence. Arnold died in 2008, and later DNA tests from his exhumed remains didn’t match that found on the Tylenol bottles.

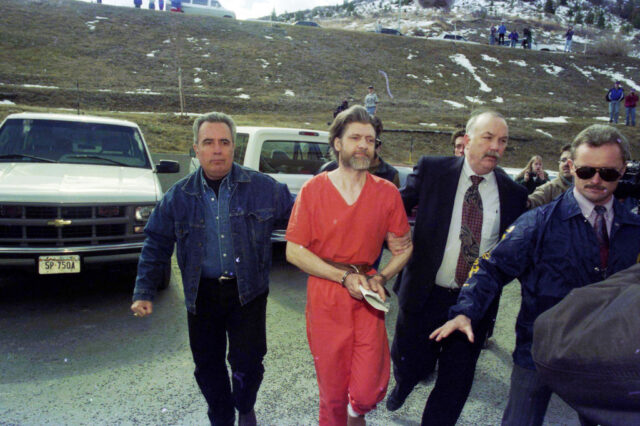

A final suspect was Ted Kaczynski – AKA, the “Unabomber.” While Kaczynski has denied involvement, the FBI requested DNA samples from him, as the first bombings attributed to him had occurred in Chicago between 1978-80. Additionally, he’d sometimes stay with his parents at their home in the city’s Lombard suburb.

Copycats pop up across the United States

The Chicago Tylenol Murders sparked hundreds of copycat incidents across the US. In 1986, three deaths were attributed to the tainting of gelatin capsules – one woman in Yonkers, New York, and two individuals from Washington state. The latter two were later found to have been committed by the wife of one of the victims.

In 1991 (and, again, in Washington), Stanley McWhorter and Kathleen Daneker died after ingesting potassium cyanide-laced Sudafed capsules. A third person, Jennifer Meling, went into a coma after taking the same medicine but later recovered. In the end, it was found that her husband Joseph Meling was behind the tampering.

A positive change came out of the Chicago Tylenol Murders

While seven people died as a result of the Chicago Tylenol Murders, there was one positive to come from their deaths. Federally, reforms were passed to better secure over-the-counter medication, and several anti-tampering laws were enacted. On top of this, pharmaceutical, consumer, and food product manufacturers developed tamper-proof packaging, with the former making an effort to move away from capsules, toward solid tablets.

More from us: Delphine LaLaurie Tortured and Killed Enslaved People in Her New Orleans Mansion

Despite their profits severely dropping following the 1982 murders, Johnson & Johnson gained public favor for their swift and effective action upon learning of the tainted capsules. The company later reintroduced extra-strength Tylenol capsules to store shelves, this time with triple-sealed packaging and steep discounts.