Let’s take a trip down memory lane and dive into the hustle and bustle of jobs that ruled the scene three centuries back. Back then, the workforce looked a lot different than it does today. From skilled crafters to essential folks, these professions kept their communities alive. You won’t find any cubicles or laptops in these jobs; we’re talking about professions that were pivotal in setting the stage for the jobs we know today.

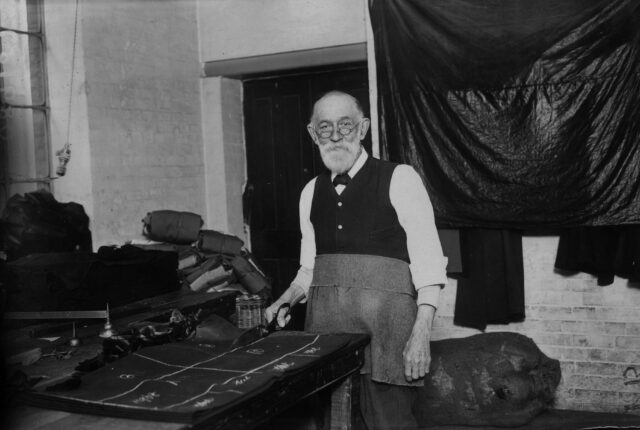

Tailor

In the 18th century, tailoring emerged as a popular and indispensable profession in both Europe and colonial America. The production of clothing was a labor-intensive process that involved various stages, from harvesting fibers to weaving thread into cloth and assembling the final outfit.

In Europe, tailoring flourished as a respected trade, with aspiring tailors undergoing rigorous apprenticeships with the hopes of joining esteemed guilds. Alternatively, in colonial America, where most individuals lacked the time and skills to craft their own clothing, tailors were in high demand, especially in settled areas away from the frontier. Where European tailors often specialized in specific garments and clientele, colonial tailors broadened their markets, creating clothing for both enslaved people and the highest-ranking elites.

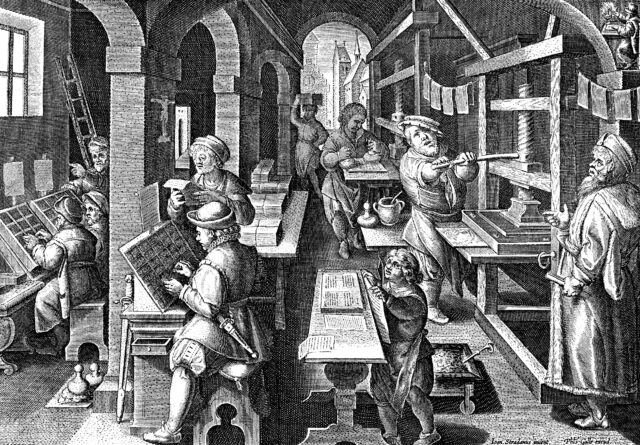

Printer

In the 18th century, the profession of printing emerged as a highly popular and influential occupation in both Europe and colonial America. The widespread demand for printed materials, ranging from newspapers and pamphlets to books and legal documents, fueled the growth of the printing industry. In Europe, printing was often associated with the rise of the Enlightenment and the circulation of philosophical and scientific ideas. Alternatively, in colonial America, where the press played a crucial role in fostering the spirit of independence, printers were essential figures in the dissemination of revolutionary thoughts.

Being a printer was no easy job. Typesetters arranged individual pieces of metal type to form the text of the newspaper, with each letter, punctuation mark, and space created by a separate piece of type. Then, the type was inked, and sheets of paper were carefully placed onto the inked type. Intense pressure was applied to create an impression, and the paper was then manually lifted off the type, with the printed sheets set aside to dry. This whole process was repeated several times to create multiple copies of the same printed material.

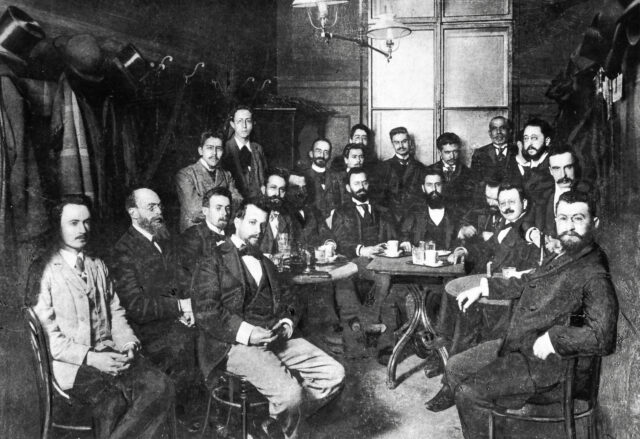

Coffee shop owner

In the 18th century, being a coffee shop owner was a popular profession in both Europe and colonial America. Coffee houses became hubs for social, intellectual, and political conversation and debate, with discussions taking place over a hot cup of coffee. However, coffee houses did not serve the kind of coffee we are used to today. Instead of prioritizing taste, coffee of the past was consumed for its physical effects, making for a rather bitter brew.

It is important to note that in both Europe and colonial America, coffee houses were predominantly male-centric establishments, as women were often barred from entering.

Alewife

Women of the 18th century found a unique avenue for generating income by working as alewives, brewing, and selling ale from their homes. This occupation offered women the opportunity to capitalize on their domestic skills while also contributing to their family’s income. Alewives would often brew beer as a household staple, and any surplus production would be sold to local communities to generate a profit.

However, over time, the image of the alewife underwent a transformation, and the profession gradually developed a negative reputation. As the brewing industry professionalized and larger breweries gained prominence, alewives became stigmatized. They began to be seen as immoral and dirty, and in some instances, these women were even labeled as witches. Over time, several strict laws were put in place to push women out of the business, eventually making it another male-dominant profession.

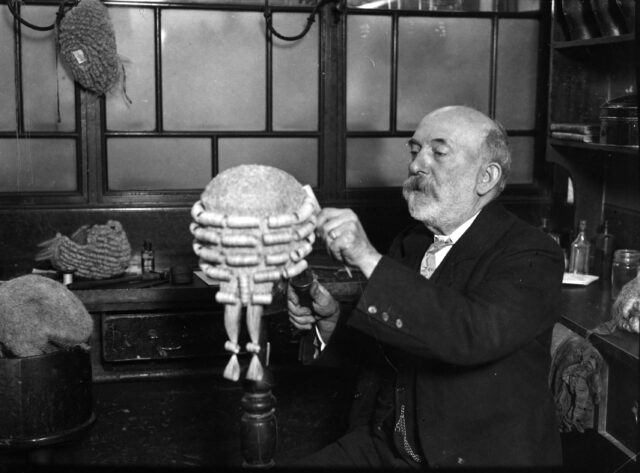

Wigmaker

Powdered wigs were all the rage in 18th-century Europe, and so wigmakers reaped the benefits of booming business. Wigs were not merely fashionable accessories but symbolized social status, wealth, and style during this period, and as such, the demand for wigs soared among the aristocracy and upper classes. With this kind of clientele, wigmakers could achieve considerable success both financially and in reputation.

In colonial America, powdered wigs also had their moment of popularity, but wigmakers were fewer in number. Many people achieved the look by powdering their own hair instead of purchasing a wig. However, over time, the powdered wig dropped in popularity in both Europe and colonial America. It became a symbol of class inequity and never really made a return in mainstream fashion.

Apothecary

In the 18th century, the occupation of an apothecary stood as a popular profession, both in Europe and colonial America. Apothecaries played a vital role as medical practitioners, herbalists, and purveyors of remedies during a time when the understanding of healthcare was deeply rooted in herbal and botanical knowledge. These skilled individuals operated apothecary shops, where they not only dispensed medicines but also concocted a variety of remedies, tinctures, and elixirs.

Read more: Funeral Directors Don’t Want the Public to Know These Things About Their Job

Their expertise made them invaluable sources of medical guidance in communities where access to formal medical practitioners was limited. In more isolated communities, physicians would double as apothecaries, handing out their own medications rather than confine these remedies to a designated storefront. While the traditional occupation of apothecary may no longer exist, a modern version would be a pharmacist.