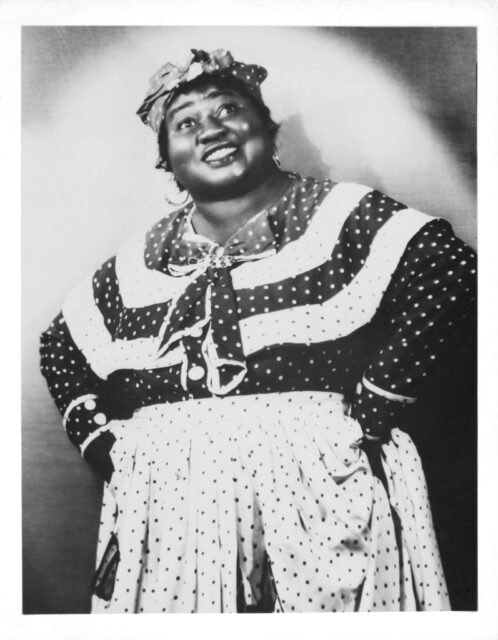

Hattie McDaniel paved the way for herself and other African-American actors and entertainers in Hollywood. With a career that spanned decades and saw her appear in over 300 movies, she broke barriers, but also had to continually fight against the racial ideologies and segregation of the era. Her most memorable performance was as Mammy in 1939’s Gone with the Wind, for which she won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress.

Hattie McDaniel performed with traveling troupes

Hattie McDaniel was born in Wichita, Kansas on June 10, 1893. She was the 13th child of an American Civil War veteran who’d served with the 122nd United States Colored Troops and sustained significant injuries. Her mother was a gospel singer.

In 1900, her family moved to Fort Collins, Colorado, before relocating to Denver, where the future Academy Award winner discovered her talent as a singer and performer. During her first year of high school, she entered a contest sponsored by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and reportedly won first place for reciting Convict Joe.

By the time she was in high school, McDaniel was working as a professional singer, dancer and actor with traveling troupes. She often collaborated with her siblings, but branched out following the death of her brother, Otis, in 1916 and soon became the first woman of African descent to sing on the radio.

Looking for greener pastures

In 1924, the Great Depression left performance opportunities pretty thin, so Hattie McDaniel took a job as a ladies’ washroom attendant at a club near Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The owners heard her singing, and, despite typically only hirig White performers, made an exception for McDaniel. She performed there regularly for about a year before deciding she wanted to see if there were greener pastures in Hollywood.

When McDaniel got to Los Angeles, she quickly landed a part on a radio broadcast called The Optimistic Do-Nuts, which led to additional opportunities. In 1931, she was cast as an extra in a musical. A year later, she secured a role in The Golden West as a housekeeper.

While this was the first role of that type that McDaniel accepted, it was far from the last. The simple truth is there weren’t many roles out there for African-American women, and the majority of them were as characters in service roles. Wanting to continue her life as a performer, she kept accepting roles as a domestic worker.

Responding to criticism

In 1934, Hattie McDaniel landed a role in the film Judge Priest and even sang a duet with Will Rogers. The following year, she acted in The Little Colonel with Lionel Barrymore and Shirley Temple. This was followed by more prominent roles in the likes of Alice Adams (1935), China Seas (1935) and Murder by Television (1935).

However, not everyone was as enamored with McDaniel’s roles as she was. Despite working steadily in the mostly-White film industry, she received criticism from organizations, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), who believed she was contributing to the perpetuation of negative stereotypes about African Americans.

McDaniel’s response to such criticism was simple and straightforward: she would rather play a maid than be one. Even if she was acting in servants’ roles, she often did so in a way that made them anything but subservient. In fact, they were often independent and sassy enough to make some White audiences uncomfortable.

Gone with the Wind (1939)

Of all her roles, one earned Hattie McDaniel an Oscar, making her the first person of African descent to be given an award by the Academy. The part in question: Mammy in Gone with the Wind (1939). The movie was based on the Margaret Mitchell novel of the same name, and it starred the likes of Vivien Leigh and Olivia De Havilland. It remains the highest-grossing film of all time when you adjust for inflation.

Despite her talents, McDaniel never believed she’d secure the role, given her reputation as a comedic actor. She shouldn’t have doubted herself, as she won the part, with one source claiming that she even had the support of Clark Gable.

McDaniel received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal of Mammy, and her acceptance speech netted her even more criticism from the African-American community. Some thought she shouldn’t have accepted the role of someone who wasn’t just enslaved, but who spoke nostalgically of the Old South.

Ironically, despite the fact she won an award for her role, McDaniel and the other Black actors in Gone with the Wind weren’t allowed to attend the film’s premiere at Loew’s Grand Theater in Atlanta, Georgia, due to the state’s segregation laws. She did, however, attend the Hollywood premiere.

Hattie McDaniel’s later life and death

Despite her Oscar win, Hattie McDaniel’s film career slowly wound down in the 1940s, with her taking roles alongside the likes Bette Davis and Humphrey Bogart. She eventually returned to radio as the star of Beulah, a nationally syndicated program. She was, again, playing a maid, but did it in a way that went against the stereotypes the NACCP had issues with, earning praise from the organization.

During the Second World War, she was a member of both the American Women’s Voluntary Service (AWVS) and the Hollywood Victory Committee. As the chairman of one of the latter’s divisions, she enlisted several of her friends, performed at USO shows and attended rallies to promote the sale of war bonds.

McDaniel died of breast cancer on October 26, 1952. After she passed away, she received several honors, including not one, but two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. She was also inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame in the 1970s, and the US Postal Service even issued a commemorative stamp in 2006 to honor her legacy.

What Happened to Hattie McDaniel’s Oscar following her death?

Prior to her death, Hattie McDaniel had stated that she wanted her Oscar to be given to Howard University. However, it would take a while to get there. Following her passing, the IRS claimed the actor owed over $11,000 in taxes and ordered everything she owned, including the Academy Award, be sold to creditors to pay the balance.

Many years later, the award wound up at Howard University, where it was put on display in the drama department. It was only there for a short while, however, as it went missing sometime in the 1960s or ’70s, never to be seen again. While several theories popped up as to what happened to the award, no one was ever able to definitively solve the mystery.

More from us: Raquel Welch: The Gorgeous Bombshell Who Beat Hollywood’s Dinosaurs

In the years that followed, calls were made for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to replace the Oscar, all of which were denied, as doing so goes against the Academy’s rules. However, it was announced in September 2023 that the award would be replaced and given to Howard University, at a ceremony aptly titled “Hattie’s Come Home.”