Most people have heard the saying “beauty is pain,” but some have taken it literally. Throughout history, women have gone to great lengths to make themselves look pretty, sometimes putting their lives in danger. Don’t believe us? Check out these historical beauty trends.

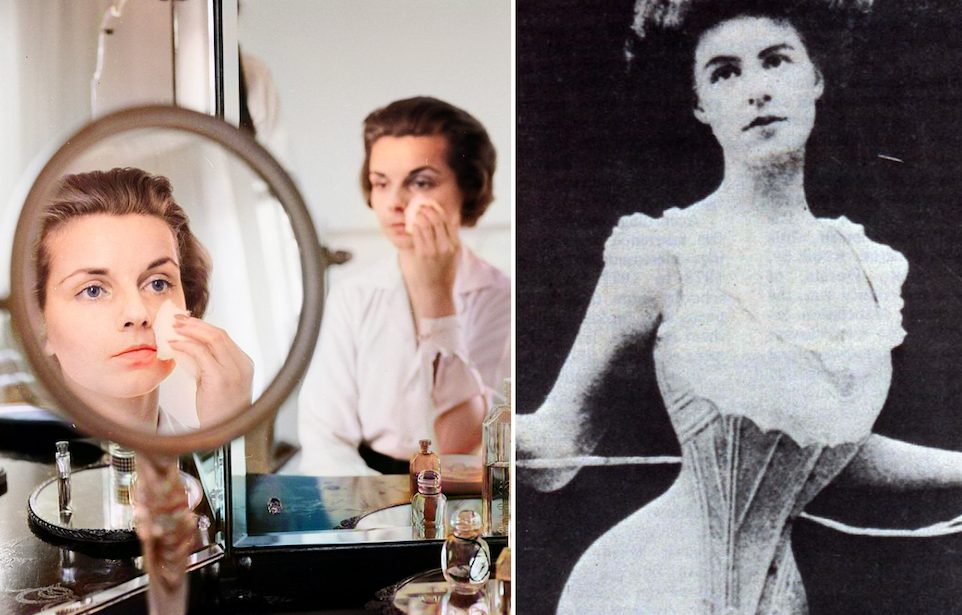

An hourglass figure

When you think of the Victorian Era, one of the first things that come to mind are corsets. Worn beneath dresses to give the appearance of an hourglass figure, they were often cinched incredibly tightly, causing numerous health issues.

Women experienced fainting spells due to their inability to take deep breaths, and they were more susceptible to tuberculosis and pneumonia. Worse still, corset wearing resulted in the moving of internal organs, the warping of ribs into an “S” shape, and a permanent misalignment of the spine.

Blonde Bombshell

American actress Jean Harlow was a leading sex symbol of the early 1930s. She was nicknamed the “Blonde Bombshell” and the “Platinum Blonde” because of her distinctive hair color.

In order to achieve her platinum look, Harlow applied a mixture of Clorox, ammonia, Lux flakes, and peroxide to her head. Mixing together ammonia and Clorox creates a noxious gas that can lead to kidney failure, which she died of at the age of 26. While not proven, many believe her hair routine to have been a direct cause.

Painting your face with lead

Some people will go to great lengths to ensure they look beautiful, even if that means slowly poisoning themselves. To make themselves appear pale, women in ancient Rome, Greece, and the Victorian Era powdered their faces with makeup laced with white lead.

The belief was that looking pale equated to status and wealth; the paler someone was, the less they worked. In ancient Rome, women powdered their faces with lead, while the Greeks used lead face masks. Victorian women used an expensive Venetian ceruse made with white lead and vinegar.

Lead makeup caused a host of issues. It corroded the skin, causing lesions, scarring and blemishes, and attributed to greying hair, constipation, and abdominal pain. Extended use resulted in paralysis, brain swelling, and organ failure.

Speaking of looking pale…

Makeup wasn’t the only way women made themselves appear pale. During the Middle Ages, it was common for women to undergo bloodletting in order to achieve the desired ghostly look. According to Introduction to Cosmetic Formulation and Technology, this was achieved by placing leeches on one’s face and letting them feast on blood.

We know it was common to use leeches as a form of medical treatment, but beauty? We think we’ll give this trend a pass.

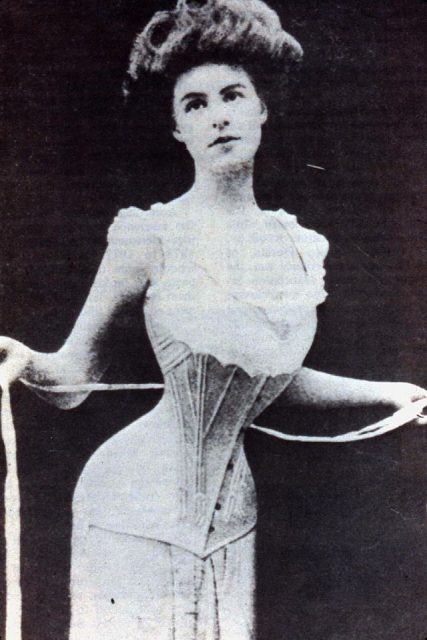

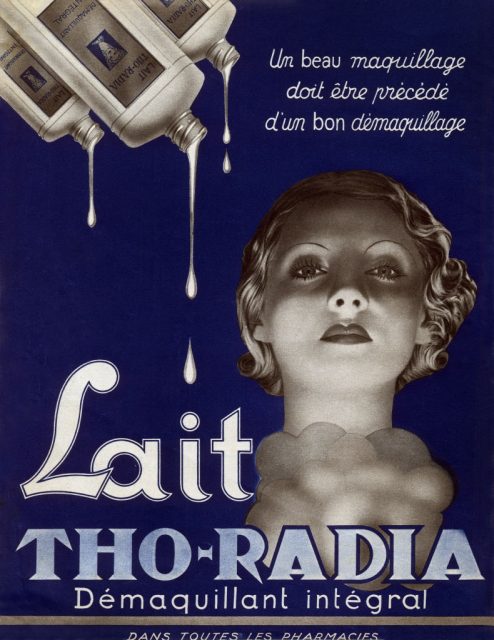

You’re positively radiant

When Marie and Pierre Curie discovered radium in 1898, cosmetic companies were eager to incorporate it into their products. Beauty brands Radior and Tho-Radia were especially popular during the 1920s and ’30s.

Along with makeup, radium found its way into everyday hygiene. During World War II, toothpaste containing it was sold in Germany. Called Doramad, its label advertised that the radioactive properties increased “the defenses of teeth and gums” and “gently [polished] the dental enamel” to produce a whiter smile.

Thankfully, the effects of radiation poisoning became common knowledge and the products were removed from the market.

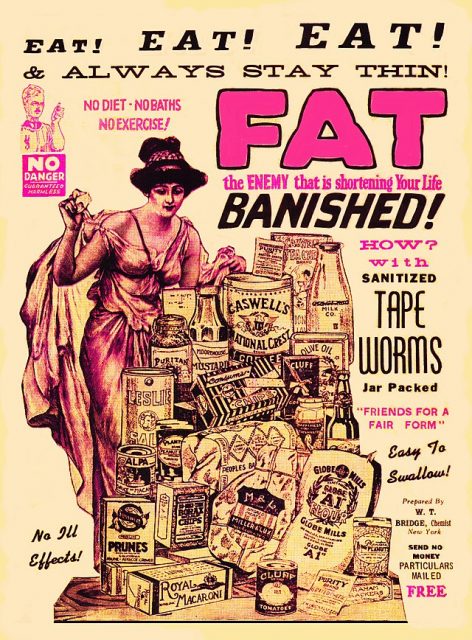

Tapeworms + food = weight loss?

The average person wouldn’t want a tapeworm in their digestive tract, but did you know the parasite was once promoted as an effective weight-loss treatment? In Victorian England, advertisements discussed their benefits, leading to the sale of pills containing tapeworm eggs.

The “science” behind this was that the tapeworms would ingest part of what their host ate, allowing someone to eat whatever they wanted without gaining weight. Once the desired weight was achieved, the tapeworm was removed with unusual and rather dangerous methods. One involved holding a glass of milk near one’s orifices, while another saw the insertion of a cylinder into the digestive tract.

Whether or not people actually ingested tapeworm-infested pills is debated by historians. It’s speculated the pills were placeboes intended to dupe desperate individuals.

Poisoned pupils

Despite having a pretty name, Belladonna is considered one of the most poisonous plants on the planet. However, that didn’t stop people from using it in their beauty routine.

In both the Victorian Era and during the Italian Renaissance, it was desirable to have big, watery eyes. In order to achieve this look, women used drops with Belladonna to dilate their pupils. Extended use often led to blindness.

Perms require dedication

Perms regularly come in and out of fashion. While today we have at-home kits, people in the early 1900s had to use a permanent wave machine, invented by Charles Nessler.

The popularity of perms was spurred by beauty publications, which promoted curls over straight hair. An advertisement in a 1922 edition of Harper’s Bazaar read: “Science has pronounced straight hair to be freakish. Just think of the great improvement a permanent wave makes in appearance. Close your eyes and imagine fairy fingers transforming your lank strands into lovely, lasting curls, as natural looking as if you were born with them.”

The process was not like having “fairy fingers” working on your hair. In reality, it was a six-to-10 hour process involving hairdressers winding hair into curlers, painting an alkaline chemical solution onto it, and using electric contraptions to blast each section with heat.

As you can imagine, the results weren’t spectacular. The majority of women walked away with bald spots, singed hair, and plastic melted onto their heads. They also sometimes received electric shocks from the machine, which made the overall experience highly unenjoyable.

You’re blushing

Another popular makeup trick in ancient Rome was to color one’s cheeks with a mixture of red lead and cinnabar. While both are poisonous, cinnabar, in particular, is known to cause tremors, dementia, and even death.

Other concoctions contained Tyrian vermillion, red chalk, rose and poppy petals, alkanet, and crocodile dung. Those with money used red ochre imported from Belgium, while beauty seekers on a budget settled for wine dregs and mulberry juice.

X-ray hair removal

In another example of how unaware people were regarding the effects of radiation, X-ray technology was used for hair removal. Beauticians immediately began using X-rays for cosmetic procedures, and some patients had to sit for 20-hour sessions.

More from us: 100 Years of Beauty Legends that Defined their Generations

X-rays were seen as the preferred method of hair removal, as they didn’t cause pain like wax and forceps. The practice ended quickly, as patients began exhibiting issues a lot worse than minor pain – skin thickening, ulceration, atrophy, and cancer.