Got milk? Yes. Got a stomach infection? Quite possibly. If you were drinking milk a couple of hundred years ago, the safety standards were very different. There’s organic and then there’s this.

All manner of disgusting things could be discovered in the creamy mix. Some of it was even added by the dairy industry! Find out why milk became so dangerous and how the cow-fueled catastrophe was averted.

Attitudes toward disease and dairy in the 19th century

Back then, the battle for public health wasn’t exactly won. Places such as Indiana featured various messes for the unwary public to step in. As reported by the Indy Star, at one point the press wanted Indianapolis rebranded as Cowopolis. Why? Because “livestock roamed the streets and residents had to walk a gauntlet of their waste.”

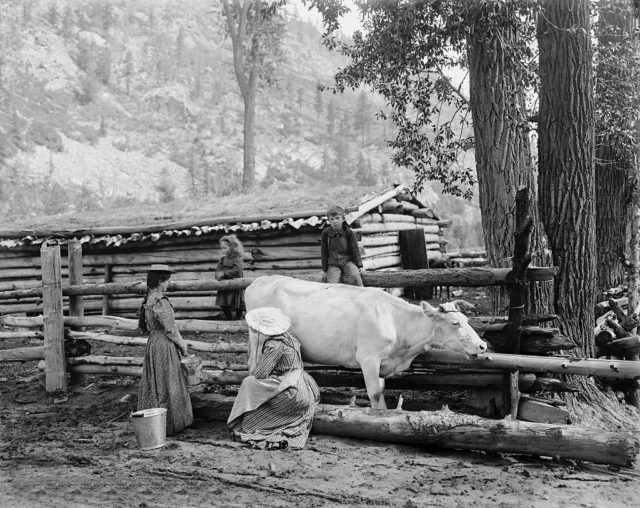

Cows produced tons of the smelly stuff. However, they also delivered what many thought was a pure form of nourishment – white, almost angelic-looking milk. The BBC notes that milk symbolized an innocent time, away from the tangled immorality of the modern age.

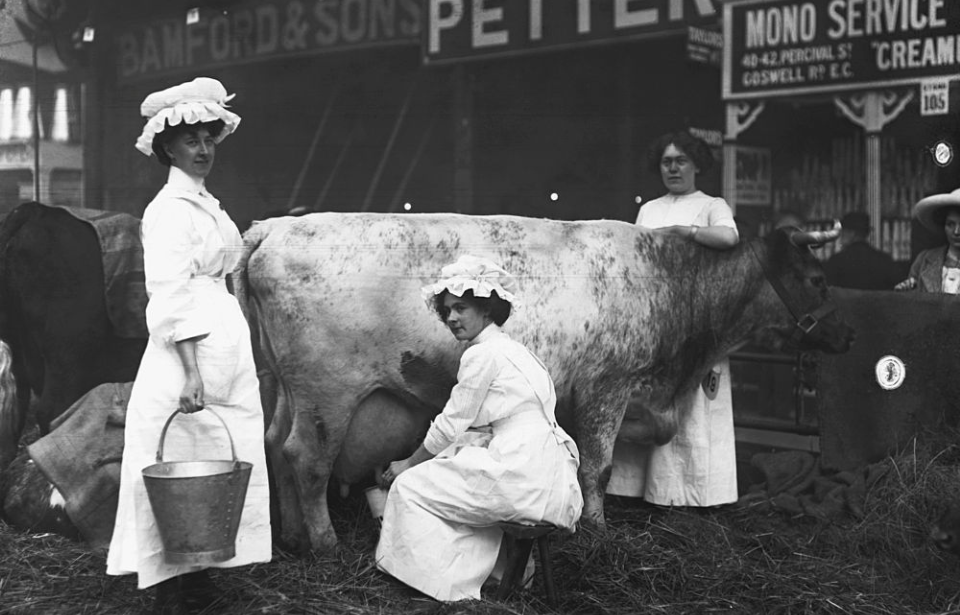

Coming straight from the cow’s udder, sure, that makes sense. Buying it, on the other hand…? Much riskier!

Dairy danger and the embalming of milk

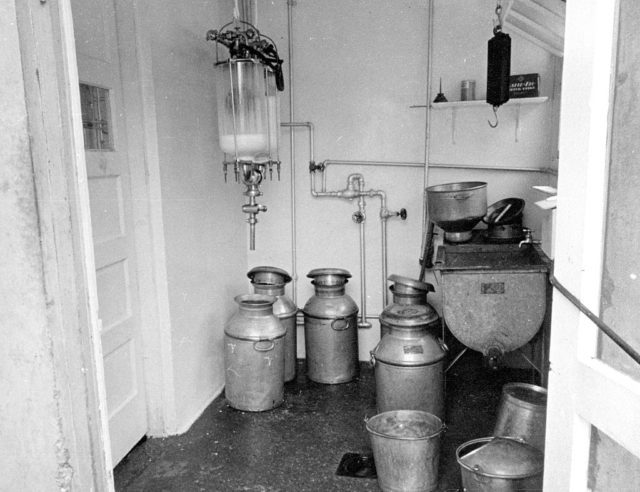

Getting milk to the general population turned into something of a free-for-all. Conditions were often unsanitary and businesses did whatever was necessary to keep the show on the road.

Milk was “more and more dangerous to consume as it moved farther from the farm where it was produced,” the BBC writes, “a breeding ground for bacteria and sometimes adulterated with chalk and water by unscrupulous re-sellers.”

The water thinned it out and the chalk was for coloring, as mentioned by Deborah Blum in her 2018 book The Poison Squad. A section of this was published in advance by Smithsonian Magazine. How did they achieve that creamy appearance? You don’t want to know.

Or maybe you do. Either way, brace yourself… excess cow brains were pureed and stirred in. Yummy.

Another unexpected ingredient of 19th-century milk was formaldehyde. This sounds wild but producers used it to extend the shelf life. Formaldehyde actually occurs naturally in milk, to a degree. However, the dairymen wound up dosing the product with increasingly high quantities, little understanding the consequences.

And the consequences were grave. As the 20th century dawned, Indiana discovered that hundreds of children had died due to the questionable content of their supposedly healthy drink. Quoted by Blum, John Newell Hurty (the state’s chief officer for public health, aka the “Hoosier Health Officer”) made his views known on formaldehyde in milk: “I guess it’s all right if you want to embalm the baby.”

These public health crusaders put the squeeze on milky business

John Newell Hurty took important high-profile steps, producing posters showing children’s gravestones to highlight the scandal.

He also released a report stating that locals were glugging down 2,000 lb + worth of dung, via their yearly milk intake. Bodily liquids. Hair. Insects. Even worms were present in some supplies.

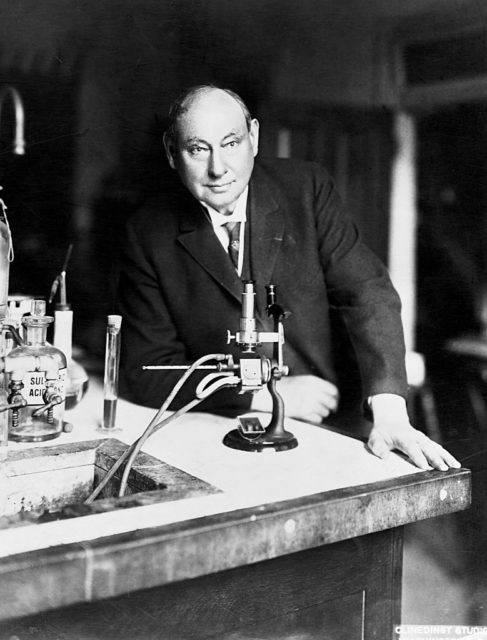

Meanwhile, the Department of Agriculture’s chief chemist Harvey Washington Wiley trumpeted a national message of healthy living. His efforts contributed significantly to the defining Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

If not for Wiley and Hurty, milk would probably still be killing off American citizens.

When they weren’t having a cow…

The two men labored to ensure that Americans understood what was in their staple food and drink. Hurty was known to taint toilets, according to the Indy Star. When guests at William English’s hotel noticed a foul taste to their water, it was exactly what Hurty intended. He’d put kerosene down the toilet. Hey, it was better than the sewage issue that English had – the rogue enforcer wanted to show how the toilet and drinking water were connected.

Hurty also angered people by digging up an Indiana farmer’s body. Why did he do this? He needed folks to pay attention to the 1891 death registration law, which some viewed as optional.

More from us: How a physician invented chocolate milk in Jamaica and brought it to Europe

Initially working for Purdue, Harvey Washington Wiley then joined the government, performing diet-based tests on volunteers. The results gave rise to a group of guinea pigs named the Poison Squad, the title of Blum’s book. Heinz and Coca-Cola were just two of the businesses Wiley had dealings with when cracking down on chemicals. He went on to work for the Good Housekeeping Institute.