Charles Lightoller signed up for a career at sea. He started working at the age of 13, eventually becoming an officer with the White Star Line, which owned and operated the RMS Titanic. What he couldn’t have anticipated from his career, however, was being part of not one but two major tragedies of the 20th century.

Second officer on the RMS Titanic

Lightoller was already working with the White Star Line when construction of the RMS Titanic was finished. He was asked to act as the first officer on the new ship for the sea trials, before being officially assigned as second officer for her maiden voyage. On April 4, 1912, Lightoller had just passed off his watch on the bridge to another officer when he felt the Titanic hit something.

He waited in his cabin to see if he was needed. Soon, his crewmates came to inform him that the Titanic had hit an iceberg and the water was already rushing in, reaching the Mail Room on the F deck. He and his fellow officers went to the bridge to hear what exactly was going on with the ship. Lightoller was soon assigned to load passengers into lifeboats and evacuate them.

Women and children first

When the ship’s captain, Edward Smith, ordered passengers to be evacuated on lifeboats, he reportedly told his officers to “put the women and children in and lower away.” Lightoller, to the detriment of many passengers, took his captain’s orders to mean only women and children should be sent out in the lifeboats – no men.

He took this order very seriously. Reports say that Lightoller ordered male passengers trying to fit onto lifeboats out at gunpoint while screaming, “Get out of there, you damned cowards! I’d like to see every one of you overboard!” Lightoller and the other officers stayed onboard as long as they could, shaking hands and saying goodbye before launching the last lifeboats.

Surviving the sinking

With no lifeboats left, Lightoller dove off the bridge into the water where he joined others hanging onto an overturned collapsible boat until they were rescued. He was not only the last person rescued by the RMS Carpathia, but was the highest-ranking officer to survive the wreck.

His rank on the ship caused him to be an important witness in the British and American inquiries about the ship’s sinking. Despite being part of such a traumatic event at seas, Lightoller continued his nautical career and his work with White Star Line.

The First World War and retirement

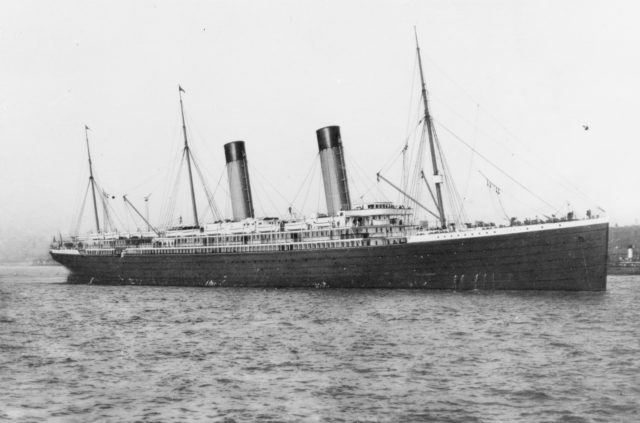

Only two short years after the Titanic sunk, the First World War started. Lightoller served in the Royal Navy throughout the war. He first served on the RMS Oceanic before being transferred to command a number of different vessels, including a torpedo boat. By the end of the war, he was awarded two service medals and earned the rank of naval commander.

Although Lightoller stayed with the White Star Line until the end of the First World War, the company decided they wanted to move past the tragedy of the Titanic and didn’t give him command of his own ship. Instead, Lightoller and his wife decided to go into partial retirement where they set up a guesthouse and purchased a 58-foot yacht. They named the yacht the Sundowner.

The evacuation of Dunkirk

By the time the Second World War came around, Lightoller was in his mid-60s so he did not serve. However, he was involved in the evacuation of Dunkirk. When German forces launched their first major offensive of the war, it wasn’t long before they invaded France and pushed many of the Allied forces back until they were left with only a small part of the French coast.

With no other option, the British ordered the evacuation of over 400,000 troops by sea from the beaches of Dunkirk. In addition to military ships, over 700 civilian vessels, including fishing boats and yachts, were used in the evacuation. Most of the civilian vessels were manned by members of the British Navy, but some civilians did take out their own boats.

Sailing a “little ship”

When the evacuations at Dunkirk began, the Royal Navy began contacting the owners of pleasure boats to be commandeered by the Navy to meet in Ramsgate, cross the English Channel, and rescue the stranded soldiers. Lightoller received his call on May 31, 1940. He agreed that the Sundowner could go to France, but only if he and his son Roger were sailing it.

Lightoller and Roger were joined by Gerald Ashcroft, a young Sea Scout. The trio left for France on June 1, 1940, alongside five other ships when they encountered another motor cruiser, the Westerly, broken down and on fire. They took the crew with them as they continued on to Dunkirk to pick up more soldiers before returning to England.

Safe arrival in England

Their vessel, which was only designed to hold 21 people, managed to fit nearly 130 men onboard. Despite their excessive weight, they were still able to evade enemy aircraft shooting at the ships traveling back to England. When they arrived back in Ramsgate to unload their passengers, a petty officer couldn’t help but wonder, “My god, mate! Where did you put ‘em all!”

In what became known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, 338,000 men were saved largely due to the help of what became known as the Little Ships, the flotilla of small boats that were used to rescue them. Lightoller not only survived the sinking of the Titanic, but also commanded one of these Little Ships, saving hundreds of lives on both occasions.