In late 19th century Japan, much attention was focused on a disease called kakke. It was bad enough to kill some, with serious health issues for those coping with the affliction.

The great and good seemingly looked everywhere, except for one important place. Steaming below them was the culprit – a delicious bowl of rice.

What was the connection between rice and kakke? How was the situation resolved? And just how does rice kill someone in the first place…?

Death by kakke

A high-profile case of a kakke-fuelled fate was the death of Kazu in 1877. She was a princess in the court of Emperor Meiji, as mentioned by Atlas Obscura. She was also his aunt, meaning the Emperor was doubly sad.

It baffled and worried the high and mighty more than most. Why was that? Because kakke preyed on the well-heeled. Something would have to be done about this mysterious but deadly curse.

The Emperor himself ultimately died of uremia in 1912. However, he too suffered from kakke, which must have caused much anxiety.

What was this deadly disease?

What did kakke do to its unfortunate victims? Atlas Obscura describes swollen legs and sluggish speech. They also write about how “Numbness and paralysis might have come next, along with twitching and vomiting.” The disease ruthlessly ground people down: “Death often resulted from heart failure.”

If that sounds a bit familiar, then you may know kakke by another name – beriberi. It took experts a long time to establish the cause of what is now a manageable, if dangerous, illness.

One of those experts was a naval physician named Takaki Kanehiro. His efforts led to rice being unmasked (make of that image what you will) as a key element behind the spreading of kakke.

Takaki Kanehiro and processed white rice

While he didn’t take the direct route to triumph, Takaki was certainly well-placed to make a diagnosis. His stomping ground of the navy was a hotbed of kakke/beriberi. How come?

Let’s go back to why kakke affected the wealthy. They feasted on a processed white rice that looked purer and was viewed as a status symbol. As with the significance of bread historically, white stuff was good whereas brown could be sent to the masses to gulp down.

What does prestigious white rice have to do with the regular soldiers of the navy? Simple – this type of rice kept longer, making it better for rations. The men kind of ate like kings. Unfortunately for them, they suffered from a right royal disease as a consequence.

The creation of white rice involved polishing. In doing this, vitamin B-1 (or thiamine) was stripped away. Without this vitamin, food can’t be effectively converted into energy. Kakke, or beriberi, or as some called it, Edo wazurai, was the result. “Edo” is Tokyo’s former name, with “wazurai” meaning illness or trouble, among other definitions.

A dangerous experiment

Takaki Kanehiro observed that crew members suffered greatly from kakke. Ironically, their higher-ups generally didn’t. This was due to them eating mainly meat and vegetables and not rice.

Did Takaki make the link between the offending foodstuff and kakke then? Not really. He figured the men needed to top up on protein instead. A 2013 article from the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine highlights his “epidemiological” approach to the problem, which wasn’t what was expected at the time. His contemporaries put kakke down to bacteria, not molecules as Takaki did.

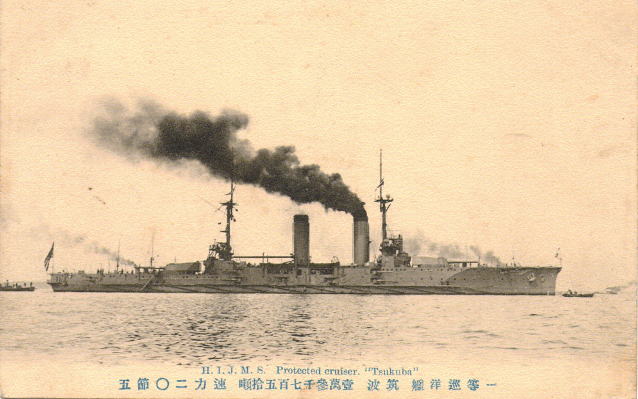

Takaki settled the matter via a high-stakes test subject, the Tsukuba. This training vessel was heading out on a trip that encompassed New Zealand, South America and Hawaii. When they set off, the kitchens would serve meat and bread alongside the typical diet of rice.

The experiment was dangerous for Takaki. He was gambling on his theory panning out. The crewmen could well have docked into port as kakke-riddled as before. However, only a small fraction contracted the disease in the end.

Great, thought Takaki, we’ll pack ‘em full of protein. The good doctor prescribed barley for what ailed them. Rich in protein, yes. But also, coincidentally, high in vitamin B-1/thiamine. He’d addressed the problem, only inadvertently.

Takaki honored

By 1929, the exact cause of beriberi would be whittled down. This was achieved by physician Christiaan Eijkman from the Netherlands and biochemist Sir Frederick Hopkins from England. Other experts were involved along the way, of course, including Takaki Kanehiro.

Eijkman and Hopkins received the Nobel Prize. Takaki had been made a danshaku, or baron, in 1905 among other honors. And he wasn’t just any old baron – he was referred to as the “Barley Baron.”

Rice cakes have killed people in the 21st century

Flash forward to 2018 and rice was forming an unusual and deadly threat to life in Japan. Not from a disease, but from the way it was eaten.

Mochi, or rice buns, grabbed headlines due to their high chewability factor. Mastication is essential if you want the buns to go down right.

More from us: The Surprising And Controversial Origin Stories Behind Some Common Favorite Foods

Those who misjudge this delicious yet dangerous treat face fatal consequences. “According to Japanese media, 90% of those rushed to hospital from choking on their new year’s dish are people aged 65 or older,” wrote the BBC.