Perhaps the most infamous curse from Ancient Egypt is that of King Tutankhamun (King Tut). He ruled from around 1333 to 1323 BC, taking the throne around the young age of eight. Although he became king at such a young age, his rule was short-lived as he died when he was just 18 or 19 years old. He was buried in the Valley of the Kings, where his tomb was discovered in 1922.

When King Tut’s tomb was excavated, there were a number of deaths associated with those involved, leading to the widely held belief that his tomb was cursed. However, a documentary on the British TV network, Channel 4, claims that the curse was reported to the public by a jealous journalist.

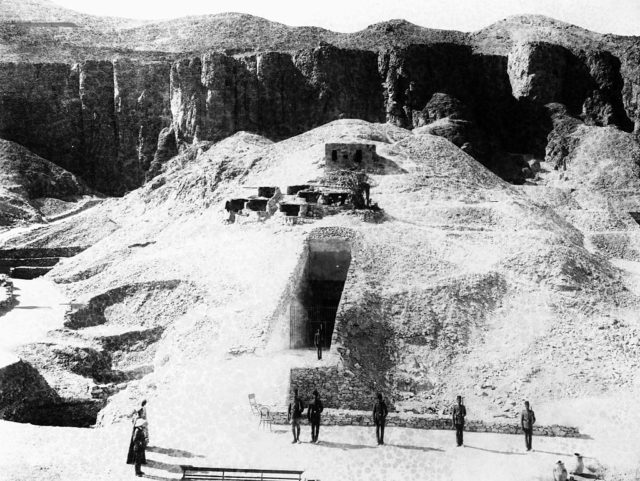

Discovery of the tomb

King Tut’s tomb was discovered by British archaeologist Howard Carter. The discovery caused a lot of media attention as it was believed that all of the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings had already been excavated. The entrance to the tomb was found in some rubble near a larger pyramid of Ramses VI, which is why it had gone undiscovered for so long. It is also likely the reason why the tomb still contained so many artifacts and had not been robbed.

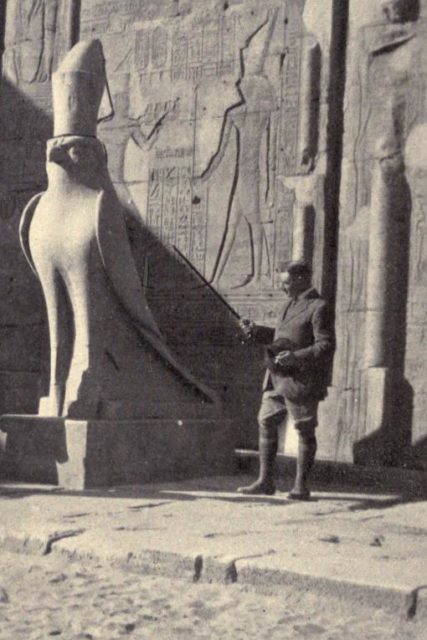

The four-room tomb for King Tut was still in remarkable condition for its age, and thousands of objects were found and cataloged. Carter discovered three coffins nested instead of each other, with the final coffin being made of solid gold. It was this gold coffin that contained King Tut’s mummy. Most famously, Carter and his crew discovered King Tut’s burial mask, which is now one of the most iconic images of Ancient Egypt. His mask is gold and inlaid with various gems and pieces of glass. It is also inscribed with a protective spell for the wearer, written in hieroglyphs.

Who started the rumor of the curse?

Despite the commonly held belief that King Tut’s tomb was cursed, Tutankhamun: Secrets of The Tomb says that the idea of a ‘hex’ was a rumor started by a disgruntled journalist covering the discovery and excavation of the tomb. Arthur Weigall, a reporter for the Daily Mail, was the center of these rumors. Allegedly, he was unhappy that Carter had given the London Times the exclusive story and was unable to get the scientific information about the discovery to tell his readers.

When the tomb was opened, Weigall heard Lord Carnarvon, Carter’s benefactor, joking as he prepared to enter the chamber. Weigall warned that if he continued being disrespectful that he would be dead in six weeks. Sure enough, Carnarvon died shortly after and his death was reported in connection to the curse. With each subsequent death, Weigall and other journalists kept pushing the idea of the curse. Weigall may have pushed this narrative, but that doesn’t change the fact that there were several eerie deaths associated with King Tut’s tomb.

Curse of the pharaohs?

The first death associated with the curse was Lord Carnarvon, who was bitten by a mosquito. The bite became infected and he died of blood poisoning that had progressed to pneumonia. Allegedly, the place where the mosquito bit him was the same location where King Tut had a lesion.

Hugh Evelyn-White was a British archaeologist who visited King Tut’s tomb, and may even have helped with the excavation. He took his own life after constantly hearing of the deaths of those involved with the tomb. Allegedly, upon his death, he wrote “I have succumbed to a curse which forces me to disappear,” in his own blood.

The apparent curse wasn’t limited to those involved in the excavation. Sir Archibald Douglas Reid was a radiologist tasked with X-raying King Tut’s body before passing it over to the museum. He allegedly got sick the day after conducting the X-ray, and was dead soon after. George Gould was a financier who visited the tomb many months after it was opened. He fell sick immediately after his visit and died of a fever within a few months.

The curse also extended to those who had never personally come into contact with the tomb or its contents. Carter gifted his friend, Sir Bruce Ingham, a mummified hand as a paperweight. It wore a bracelet that said, “Cursed be he who moves my body. To him shall come fire, water, and pestilence.” Ingham’s house burned down shortly after receiving this gift, and when he rebuilt it, it was hit by a flood.

Despite these odd deaths, the fact is that most of the crew who excavated Tut’s tomb lived out normal lifespans. In a 1986 report, archaeologist Frank L. Holt wrote, “most of Carter’s crew lived full lives,” including Carter, who lived to 60 and would have been the most likely victim of a curse. And a 2002 British Medical Journal study found “no significant association between potential exposure to the mummy’s curse and survival, as well as no sign at all that those who were exposed were more likely to die within 10 years.”

More from us: This Dagger Found In King Tut’s Tomb Is Literally Out Of This World

The idea of King Tut’s curse may have been popularized by a jealous journalist and discredited by modern research, but there are many who still believed, then and now, that the curse is real. According to Egyptologists, curses were placed on Ancient Egyptian tombs which would cause bad luck, illness, or death to those who disturbed a resting pharaoh.