More than a century ago, 25-year-old Charles Vansant dove into the waters of Jersey Shore for his first swim of the summer. The next time he emerged from the water, his body was bloody and mangled and he was on the brink of death. Vansant would be pronounced dead on July 1, 1916, triggering nearly two weeks of mayhem that would ultimately leave four swimmers dead and one injured.

Twelve days of terror

The 1916 Jersey Shore shark attacks sound just like fictional stories we all grew up with (cue the Jaws music), but around this specific time in history, sharks were the last thing most Americans were worrying about. The attacks occurred in the middle of a polio epidemic, compounded by the looming fear of possible American involvement in World War I. Throw in a deadly heatwave and a hungry shark, and the perfect conditions were set.

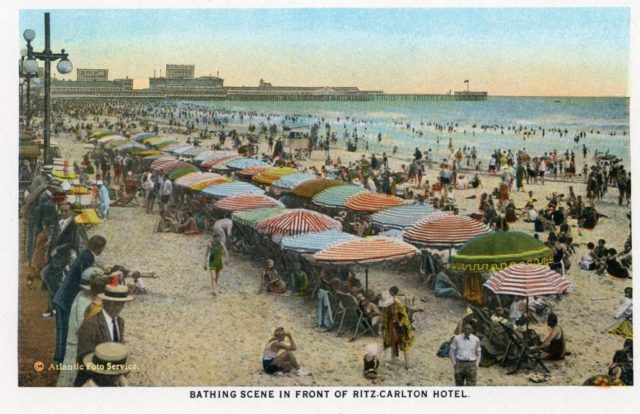

Following the death of Charles Vansant, the nation went into a frenzy over the potential danger of “man-eating” sharks. Not only was the shark attack a safety issue, but it also threatened New Jersey’s local economies that depended on beach tourism to survive. At first, beaches remained open after the July 1st attack, even though sea captains in the area reported sightings of large sharks swimming off the coast.

On July 6, a second victim fell prey to the Jersey sharks. Charles Bruder, a 27-year-old Swiss bell captain at a local hotel, was attacked while swimming only 130 yards from shore.

A shark bit his abdomen, severing his legs. As his blood stained the water red, a woman notified two lifeguards that a red-colored capsized canoe was floating in the water. When the lifeguards approached the scene with a lifeboat, they realized something much worse had happened. Bruder was hauled aboard the lifeboat but ultimately bled to death on the way back to shore.

Now that the public knew the first attack wasn’t a one-off coincidence, panic and paranoia set in. As people fled from the beaches and local resorts, fishermen headed into the water in search of the shark terrorizing New Jersey – which they dubbed the Matawan Man-Eater. Two men were dead, but the worst was yet to come.

The ‘Titanic’ of shark attacks

On July 12, the little borough of Matawan, New Jersey – 170 miles north of the first attack site – would become the most talked about town in America. When a local fishing captain spotted a large shape moving in the water under a bridge, he reported it to local police but his concern wasn’t taken seriously. In an effort to avoid another attack, the captain ran through the streets yelling at passersby to avoid the water.

Unfortunately, a group of young workers from a local factory hadn’t heard the man’s warning. After working all day in the sweltering heat, the boys were looking forward to a refreshing swim at the creek to cool off. Just as 11-year-old Lester Stillwell waded into the water, his friends watched in horror as a dark shape pulled Stillwell underwater – leaving a trail of blood in the water.

Lester’s friends immediately ran through town screaming “Shark! A shark got Lester!” A crowd gathered at the creek as locals searched the water for any sign of the missing boy. One of them, a tailor named Stanley Fisher, dove deep underwater and, after several agonizing moments had passed, he finally surfaced holding Stillwell’s mangled body.

As he stood in the water, nearly all of Matawan Creek was looking at Fisher when they saw the massive shark pull him down, sinking its teeth into his right leg. Fighting and thrashing in the water, the shark refused to let go until rescuers in a boat beat him away with an oar. Fisher was pulled out of the water with most of the flesh from his right thigh gone. He also lost hold of Lester Stillwell’s body during the attack.

According to Richard Fernicola. a local doctor and author of Twelve Days of Terror – an account of the shark attacks – Fisher’s leg was just “scratched bone.” Fisher was alive for two hours before he died at a local hospital. Stillwell’s body was found 150 feet upstream from where he was attacked.

Just 30 minutes after the brutal attacks on Stillwell and Fisher, the Matawan Man Eater struck for a fifth and final time. Fourteen-year-old Joseph Dunn was swimming a half mile from where the Stillwell attack occurred when something bit his leg. His brother engaged in a vicious tug-of-war battle with the shark, trying to free Joseph from its jaws.

Eventually, they were able to rescue Joseph and take him to a hospital where he eventually recovered from his injuries – the only survivor of the attacks, which Fernicola regards as the “Titanic of shark attacks.”

What happened to the shark?

The man-eating shark story was an instant media sensation, but what caused the unprovoked attacks? Witnesses to the first fatality reported the shark was roughly nine feet long. In the days following the first attack, several local fishermen claimed to have caught the shark responsible but both were species that were highly unlikely to cause such destruction.

On July 14, an eccentric taxidermist and famed lion tamer Michael Schliesser caught a 350-pound shark while fishing several miles from Matawan Creek where the last three attacks happened two days prior. Schliesser claimed the shark nearly sank his boat until he killed it with a broken oar.

Gutting the shark, he supposedly removed “suspicious fleshy materials and bones” that weighed fifteen pounds. Scientists identified Schliesser’s catch as a great white shark that had indeed ingested human remains. The shark was mounted and put on a display in a window of his taxidermy shop but has since been lost. The attacks stopped after Schliesser’s incredible catch, making many believe he really did catch the Matawan Man Eater.

As for where the shark came from, and how it got its taste for human flesh, wartime conspiracy theorists had their own answers. One letter to The New York Times blamed German U-boats for the New Jersey shark problem. The writer concluded:

“These sharks may have devoured human bodies in the waters of the German war zone and followed liners to this coast, or even followed the Deutschland herself, expecting the usual toll of drowning men, women, and children. This would account for their boldness and their craving for human flesh.”

Contemporary scientists suspect the shark wasn’t even a great white, but instead could have been the more aggressive bull shark. Researchers point to the Matawan Creek incident as a likely indicator the attacker was a bull shark. Unlike great whites, bull sharks can withstand living in fresh water and are known to interact with humans according to accounts from Iran.

Biologist Richard Ellis explained that the great white “is an oceanic species, and Schlesser’s shark was caught in the ocean. To find it swimming in a tidal creek is, to say the least, unusual, and may even be impossible. The bull shark, however, is infamous for its freshwater meanderings, as well as for its pugnacious and aggressive nature.”

Cultural Impacts

Sadly, these early run-ins with sharks in New Jersey set the groundwork for a large cultural shift in thinking. Suddenly, sharks were seen as ruthless and bloodthirsty monsters who should be eradicated at all costs. The belief that sharks purposefully antagonize humans led to modern misconceptions of sharks portrayed in books, TV, and movies.

Specifically, the Jersey Shore attacks inspired one of the most iconic rogue shark stories, Peter Benchley‘s 1974 novel Jaws – which was turned into the cult-classic 1975 film under the same name.

The media frenzy that erupted over the attacks sent America into a mass panic. Suddenly beaches were empty even on sweltering days and seasonal businesses suffered to make ends meet. According to Thomas B. Allen, the resort industry in New Jersey lost a whopping $250,000 dollars that summer ($2.6 million dollars today!) It took some time before the paranoia subsided and swimmers felt safe in the water once more.

More from us: Not Quite A Blockbuster: Steven Spielberg’s First Movie Made $1 In Profit

The federal government also got involved in the controversy. The House of Representatives sent $5,000 dollars to New Jersey to aid in eradicating the “shark problem,” causing shark hunts all along the shores of New Jersey and New York. Hundreds of sharks were killed during the East coast shark hunt, which is considered to be the “largest-scale animal hunt in history.”