When we think about reopening a long-buried vault, we are probably under the impression that great treasures and artifacts could be found. Perhaps some secrets will even be answered. In the case of the reopening of Lord Byron’s vault, a big secret was revealed. A really big secret.

Lord Byron, one of England’s greatest poets

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, better known as Lord Byron, was born on January 22, 1788. He was a British Romantic poet and satirist who became one of the world’s first celebrities. The tales of his mounting debts and many romantic affairs with unsuitable women earned him just as much fame as his poetry.

An adventurer at heart, he had traveled to Greece to help in the liberation of the country from the Ottoman Turks. However, while there, he developed what was likely malaria and died on April 19, 1824, in Missolonghi, Greece at the age of 36.

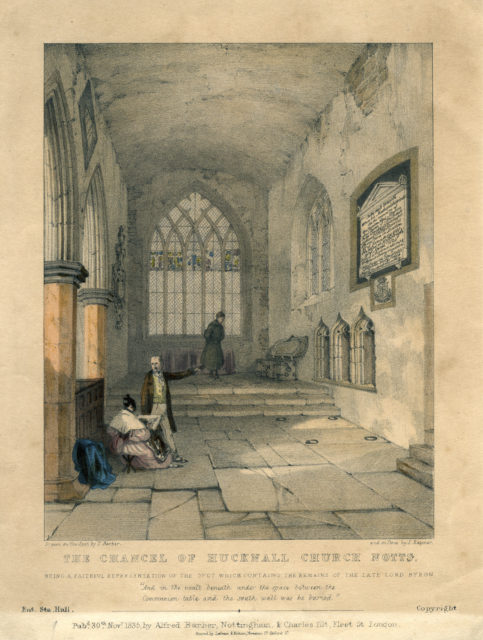

The matter of where his body would be buried was heavily argued and it took quite a while before it was decided that he’d be sent back to England. There, he’d be interred at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Nottinghamshire.

Fears that his body was not in the vault

There were controversies about the real whereabouts of Lord Byron’s remains over the years. Between 1887 and 1888, there was a restoration project in the church that raised concerns that the crypt could have been damaged or tampered with. In 1938, Reverend Canon Barber (the vicar of Hucknall parish) had his own concerns and wished to reopen Lord Byron’s vault to “clear up all doubts as to the Poet’s burial place and compile a record of the contents of the vault.”

In order to open the crypt, Barber had to write to his member of Parliament to get permission from the Home Office. He also reached out and asked permission from the surviving Lord Byron to enter the family vault. This Lord Byron excitedly agreed, and “expressed his fervent hope that great family treasure would be discovered with his ancestors and returned to him.”

With all permissions granted, Reverend Barber and a group of 40 invited guests gathered on June 15, 1938, to enter the vault of Lord Byron.

Reverend Canon Barber was the first to descend into the vault

After the stone slab was lifted and the air quality was tested by lowering a miner’s safety lamp, Barber was the first person to descend into the vault. This was a long-awaited moment and Barber had high expectations about what Lord Byron’s vault would look like and what it would contain. Unfortunately, he was disappointed by what he saw.

“It was totally different from what I had imagined,” he revealed. “To find myself in a Vault of the smallest dimensions, and coffins at my feet stacked one upon another with no apparent attempt at arrangement, giving the impression that they had almost been thrown into position, was at first an outrage to my sense of reverence and decency.”

Stunned at the disarray, he recalled, “I could not bring myself to believe that this was the Vault as it had been originally built, nor yet could I allow myself to think that the coffins were in their original positions. Had the size of the Vault been reduced and the coffins moved at the time of the 1887-1888 restoration..?”

Was the vault previously disturbed?

In reality, no one had disturbed the vault during the restoration. It was churchwarden A. E. Houldsworth, along with two other workers, who had entered the vault and cracked into the coffin housing Lord Byron right after Barber made his first disappointing descent.

Likely feeling underwhelmed at his first impression, Barber had retreated from the vault for afternoon tea with all of his guests. Houldsworth and the two other workers wanted to see what was inside, so they took the opportunity and explored for themselves.

The contents of the vault

Two coffins were visible that appeared to have been in good condition. They were covered in purple velvet, but some of their handles had been removed as well as one’s nameplate. The one that still had a nameplate was that of Lord Byron’s daughter, Ada Lovelace. In addition to these caskets were other containers filled with oddities.

“At the foot of the staircase, resting on a child’s lead coffin was a casket which, according to the inscription on the wooden lid and on the casket inside, contained the heart and brains of Lord Noel Byron,” explained Barber. Interestingly, Lord Byron’s wish had been that his body not be hacked into pieces. Obviously, his wish was not granted.

Finally, Barber peeked into Lord Byron’s coffin. He was “able to see Lord Byron’s body which was in an excellent state of preservation. No decomposition had taken place and the head, torso, and limbs were quite solid. The only parts skeletonised were the forearms, hands, lower shins, ankles and feet, though his right foot was not seen in the coffin. The hair on his head, body and limbs was intact, though grey. ”

After a long day exploring Lord Byron’s vault, Barber was satisfied that he was able to definitively say that the poet’s body was, in fact, buried at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene.

What Houldsworth (and probably everyone else) had noticed about Byron

A long-spreading rumor had been circulating that Lord Byron was laid to rest in his coffin with a massive erection. This was just a sensationalized myth, but Byron’s body did have a characteristic that was certainly just as “massively noticeable.”

Years after the reopening of the vault, Houldsworth was interviewed by Byron Rogers of the Sheffield Star, and he described what state Lord Byron’s body was in when they’d peered in. He said, “[Byron] was bone from the elbows to his hands and from the knees down, but the rest was perfect. Good-looking man putting on a bit of weight, he’d gone bald. He was quite naked, you know.”

Then, Houldsworth described a very interesting feature of Lord Byron. He said, “Look, I’ve been in the Army, I’ve been in bathhouses, I’ve seen men. But I never saw nothing like him.” He then pointed to a spot just above his knee. “He was built like a pony.”

More from us: Burt Ward, the Boy Wonder and… the Budgie Smugglers? Batman’s R-Rated Side

So there you have it! Lord Byron, the extraordinary poet, adventurer, and ladies’ man, was in fact hung like a horse.